Research: more is not better

One way in which the costs of post-secondary education could be significantly reduced without reducing the quality of undergraduates is by culling a lot of unproductive and expensive research. We do not need every faculty member in every university to spend an equal amount of time (or more) on research as teaching, especially as a great deal of contemporary research is esoteric (academics arguing amongst each other over how many angels can dance upon the head of a pin), of poor quality (badly written and superficially reviewed), and unproductive (see below for evidence).

However, all this feverish output of research is deemed necessary, because currently promotion in universities is based as much on the number as the quality of research publications, and certainly not on expertise in teaching.

The exponential expansion of university research activities

The post-secondary education system expanded rapidly from the end of the 19th century to the present day. The main way this has happened has been by increasing rapidly the number of post-secondary institutions. As post-secondary institutions – and faculty – increased, so has research activity.

Anisef, Axelrod and Lennard (2015) state:

By 1939 the number of degree-granting universities in Canada had increased to 28, varying in size from U of T, with full-time enrolment of 7000, to those with fewer than 1000 students. There were 40 000 students, representing 5% of the population between ages 18 and 24. By the early 1950s the size of the university student population was twice that of 1940 and by 1963 another doubling had taken place. Participation continued to increase in the three decades after 1980. Indeed, it more than doubled. By 2010, nearly 1.2 million students were enrolled full-time in degree programs, consisting of 755,000 undergraduates and 143,400 graduate students. In addition 275,800 students were enrolled part-time.

To meet this demand, new universities emerged, periodically from scratch, and more frequently as offshoots of existing institutions. In BC, for instance, nine new ‘teaching-intensive’ universities were created between 1990 and 2008, plus one Institute of Technology.

By 2022-23, there were 1,143,489 students enrolled in Canadian universities (Statistics Canada, 2024), a 56% increase from 1982. Since 1970, the Canadian university student population has tripled.

In 2022/2023, there were 48,258 full-time teaching staff at Canadian universities.This is a 33.9% increase from 2002/2003. In 2022/2023 there was roughly one full-time teaching staff for every 24 students in Canadian universities. Over one-third (36.7% or 17,718) were full professors, the highest rank a professor can achieve.

Anisef, Axelrod and Lennard (2015) also state:

The Canadian system of higher education, unlike that in the United States, has developed little institutional differentiation. Typically, Canadian universities seek to cultivate a mix of undergraduate, graduate, and professional education, as well as a vibrant research culture, upon which higher institutional status and more abundant external resources often depend.

So, as the system has rapidly increased, the total amount of time devoted to research has similarly expanded exponentially.

The decrease in quality in research

This widespread increase in research was not what was intended when governments rapidly expanded post-secondary education. The main goal of the expansion was to increase access and meet the needs of business and industry. For instance, In British Columbia, the expansion between 1990 and 2008 resulted in what were meant to be ‘teaching intensive’ universities. The nine new ‘teaching-intensive’ universities were in most cases based on converting two-year university colleges (with no or little research activities) into full universities, while others were converted from two-year vocational colleges. However, very quickly the existing faculty demanded full tenure with research time equal to those in the more established research universities.

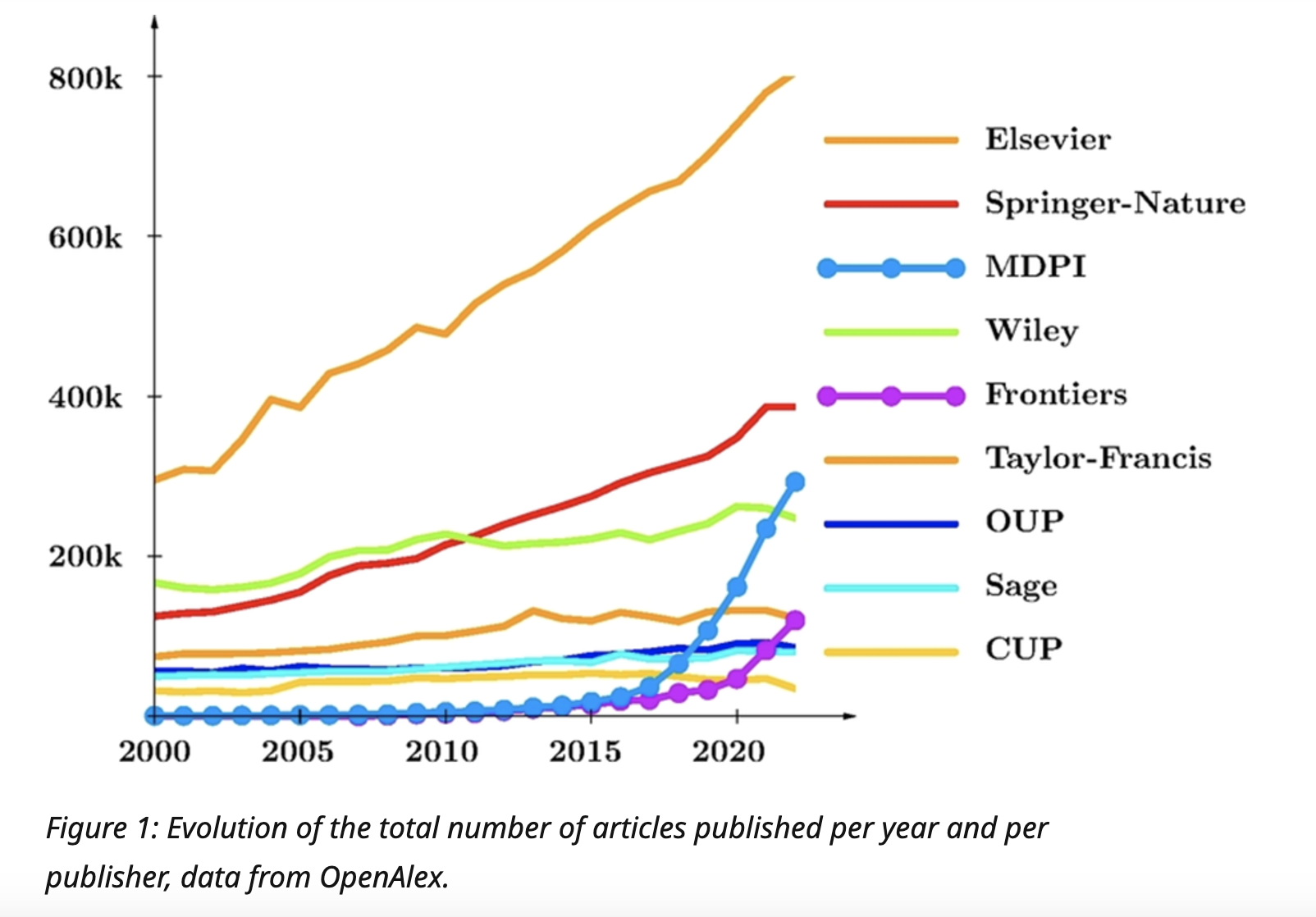

This has resulted in an exponential growth in research activities, certainly as measured by research publications. Pier et Romary (2024) in a recent publication reported an exponential growth in research publications between 2016-2022, coinciding with a dramatic reduction in the time for peer review. They concluded:

Based on the results of this study, we can ask ourselves whether the current system is sustainable. The answer is clearly no. Exponential growth in the number of publications is not compatible with maintaining scientific quality and ensuring confidence in the results, guaranteed by a careful and thorough peer review process.

What should we do?

At the moment, in Canada there is roughly one tenured faculty for every 24 students. This should be enough to enable high quality teaching if the faculty have enough time to teach, and use modern teaching methods and technology.

As I argued in a previous post, we need to increase the number of full-time, tenured teaching faculty whose main function is teaching, in order to reduce overall costs. This would coincide with an (eventual) reduction in the overall numbers of tenured research faculty. This could be done as follows:

- ensure that tenured teaching faculty have adequate training in post-secondary education teaching methods so that they can handle larger class sizes effectively

- reduce/eliminate the adjunct faculty (some of whom would become tenured teaching faculty)

- reduce (over time) the number of tenured research faculty within a post-secondary system by approximately 30% (higher in some institutions than others)

- increase the teaching load (courses and students) for tenured teaching faculty to roughly double the current teaching load of tenured research faculty

- enable tenured teaching faculty to have adequate time (20%?) for professional development/maintaining their academic knowledge.

It is particularly important to take a system-based approach. The reduction in tenured research professors in a large, research intensive university would be less than in a regional, small university. In these smaller universities, research would focus on specific areas of local interest, such as agriculture, forestry or mining. Some academic departments in some institutions would have no or very little academic research. This would become more acceptable to faculty if expertise in teaching becomes the main criterion for promotion in universities.

Is this elitist? Would this leave large research universities such as McGill, the University of Toronto and UBC with a greater proportion of tenured research professors than smaller regional universities such as the University of the Fraser Valley, Algonquin University or Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières? Yes, because we need more differentiation, not only between research and teaching professors within an institution, but also between institutions. This will not only release more faculty for teaching, but increase the quality of the research that is being done.

Will full-time university teaching faculty be less effective without a research mandate? Some will, but many won’t. Full-time teaching faculty are more likely to be assigned to foundation (first year) and second year courses, with tenured research faculty teaching advanced undergraduate and graduate courses. Again, it’s the mix that matters.

Don’t get me wrong

I think the rapid expansion of post-secondary education is a good thing. In Canada it has opened up the opportunity of a higher or technical education to millions who would not have had the chance without this expansion. Canada in particular has an outstanding technical and vocational system. Its polytechnics in particular have managed to straddle teaching and applied research very effectively. Canada also has some world class research universities. I believe that research is an absolutely essential part of any university mandate, whether the university is big or small.

But there are now over 200 universities in Canada. Not all can – nor should – strive to be elite research universities. Even in some of the large research universities, too many faculty are chasing esoteric or low value research, not so much to increase the knowledge base of their subject discipline, but to get a leg up in a fiercely competitive employment environment. There is evidence that too many faculty (and publishers) are trying to game the system by inflating research publications. All this feverish research activity takes away time that could be better devoted to teaching. Combined with modern teaching methods (see earlier posts) more time spent overall on teaching and less on research would enable costs to be substantially reduced.

However, this change of balance between research and teaching needs to be done carefully and intelligently. Each institution needs to look at its mandate, its local needs, and its strengths and weaknesses, both in teaching and research. However, the operation and culture of universities in particular has not changed in line with their change in mission over the last 100 years. It’s about time they did, particularly with regard to research.

Over to you

- Do you think there is too much poor quality or useless research being done?

- Do you agree that we need more differentiation, with research focused more on ‘elite’ universities?

- Can teaching at a post-secondary level be effective without 40% of faculty time being devoted to research?

- What could persuade faculty to give up most of their research time to teaching?

Up next

I will examine the possibility of three year rather than four year undergraduate programs then will provide a summary of the main steps I am suggesting for reducing the costs of programs and why it is so important. However, that will not be for a week, as I am taking a short break.

References

Anisef, P., Axelrod, P. and Lennard., J. (2015) Universities in Canada, The Canadian Encyclopedia

Statistics Canada (1983) A Statistical Portrait of Canadian Higher Education: From the 1960s to the 1980s Ottawa: Ministry of Supplies and Services

Statistics Canada (2024) Canadian postsecondary enrolments and graduates, 2022/2023 Ottawa: Statistics Canada 20 November 2024

Statistics Canada (2023) Number and salaries of full-time teaching staff at Canadian universities Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1 November 2023

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Great post Tony. I couldn’t agree more. Coping with very greedy commercial publishers and predatory open access strains the system.