The challenge

In an earlier post, I suggested that post-secondary institutions needed to reduce the costs of degrees or diplomas by 30% to win back trust and support from government in particular, the general public in general. But how to do this without reducing enrolments, cutting programs or lowering quality?

One solution: modern, evidence-based course and program design

Although we have a mass system of education now serving in Canada more than two thirds of high school students and increasing numbers of lifelong learners returning for new or further qualifications as the economy changes, we still have an artisanal approach to teaching, with tenured professors as the artisans, individually designing each of their own courses, assisted by their apprentices, usually in the form of low-paid, relatively inexperienced, part-time adjunct faculty. There is a heavy emphasis on content delivery and student assessment, with the tenured professor determining what content is to be delivered, and part-time, low paid adjunct faculty involved in both the delivery of content and the support and assessment of students.

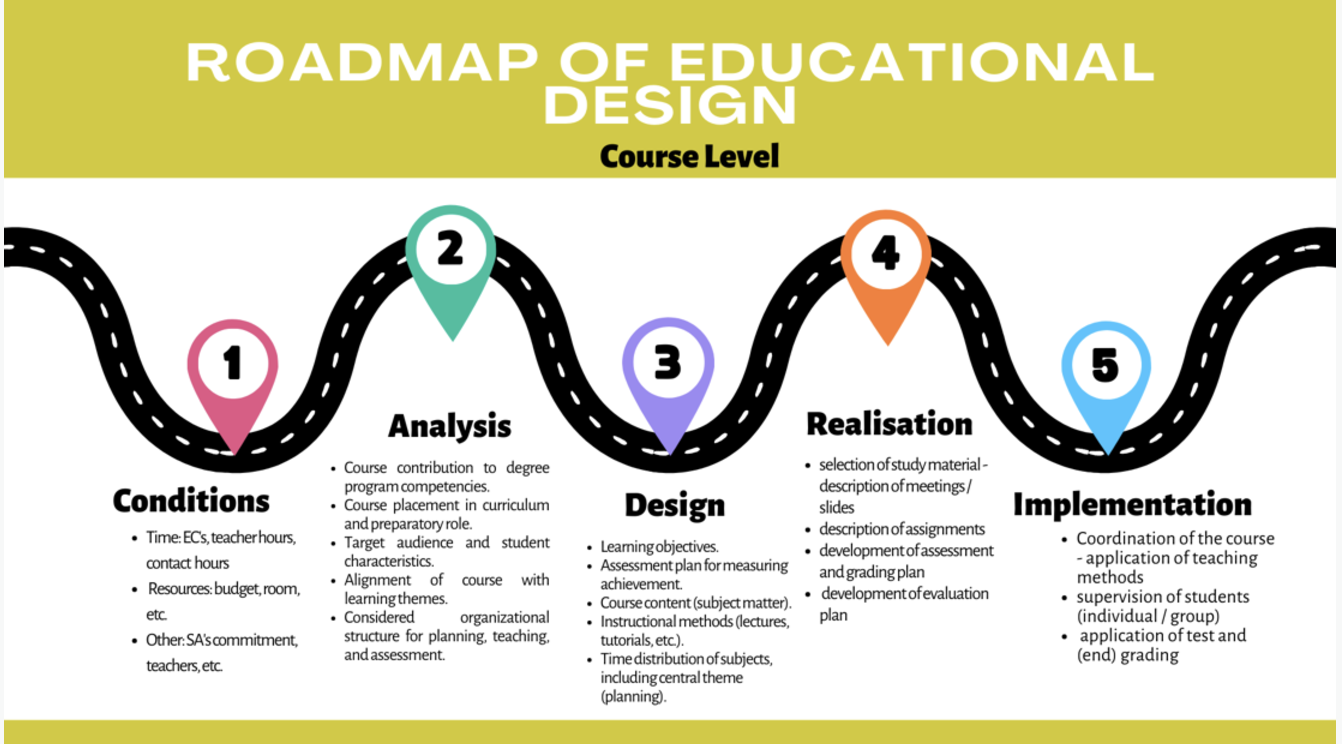

However, in the last 100 years, there has been a revolution in teaching methods. This revolution is focused on research into how people learn, what motivates them, and how they think. However, it is not rocket science. It focuses on setting clear learning objectives, control of student workload, methods of supporting students in their learning, including timely feedback, a focus as much on skills development as content acquisition, and on authentic ways of measuring learning. It even has a name: learning (or instructional) design. This knowledge in most cases is within post-secondary institutions, but it is mainly within Centres for Teaching, Learning and Technology. Instructors can learn about learning design from these specialists, but in recent surveys, less than 10 per cent of faculty make the effort. Although this knowledge is within most institutions, the problem is scaling up, as was discovered during Covid, when all teaching went online. Although the Centres for Teaching did a great job, they could not suddenly move to fully supporting 10 percent of courses to fully supporting 100 per cent of courses. Learning design needs to be built into the core of the teaching.

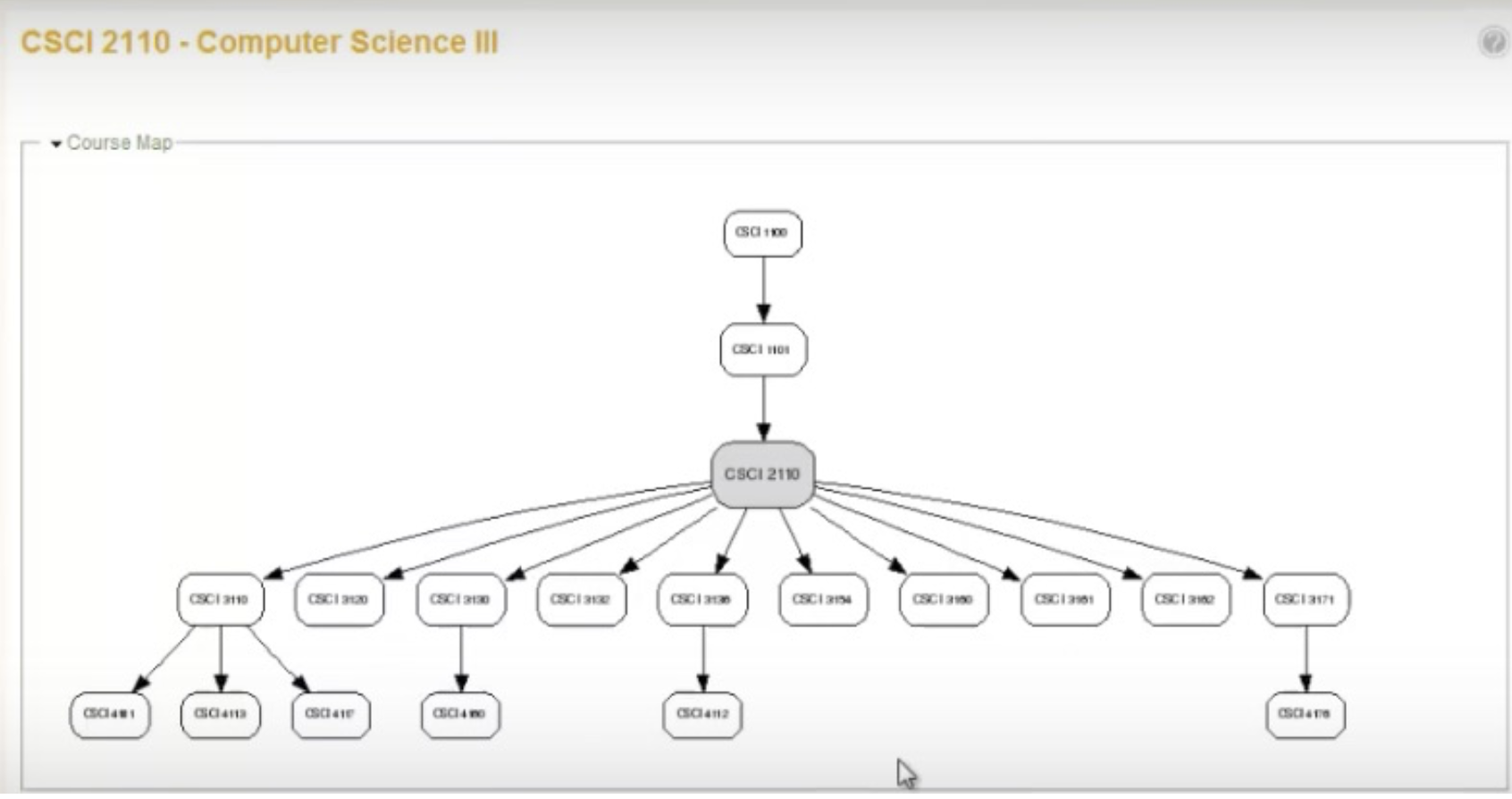

It is also necessary to think about the integrated design of whole programs. Rather than a randomised selection of courses at different levels, dependent on the faculty available and willing to teach a particular course, more emphasis needs to be given to developing and improving key skills throughout a program, and ensuring courses are taught in the appropriate sequence. For example, if critical thinking is to be developed in the first year of a program, to what level, how will it be assessed, and how will courses in the second year increase a student’s competence in critical thinking? What must students learn in year one that is necessary for progress in year two? And in terms of cost savings, how do we avoid redundancy and repetition within the program as a whole? The Department of Computer Science at Dalhousie University has used a program called Daedalus that enables such a process to be mapped out, and which students can also use to see what knowledge they need at each phase of the program. This way, a great deal of redundancy and duplication in teaching can be avoided.

And now is the time to mention technology. There has been a revolution in educational technologies, in particular, the Internet, learning management systems that support students when they are learning away from the campus or the classroom, and now artificial intelligence. As a result, professors and instructors no longer need to deliver content, nor even assess content acquisition, per se. What students need to learn now is knowledge management: how to find, assess, and appropriately use knowledge, and in particular, how to develop core skills such as critical thinking, independent learning, knowledge management, and problem-solving (these are often the skills employers claim are lacking in new graduates).

As institutions have moved more and more into fully online and blended learning, the aim has been to ensure that the learning is ‘as good as’ traditional classroom learning. The mandate though has never been to show that online or blended learning combined with modern learning design can produce the same or better results at less cost. To do so would threaten jobs. But now is the time to start doing that. Using modern design and appropriate technologies used in appropriate ways, costs could be dramatically reduced. In essence, the aim is to make the students do the work by creating a learning environment that supports their learning all the steps of the way. We know how to do this.

Changing jobs and roles

The role of the tenured faculty member would change. They would be in charge of course design, the setting of learning objectives (including skills), guidance on where to find appropriate content, and the best methods of assessing students’ acquisition of the learning objectives.

One tenured professor could manage more classes and more students if they are not responsible for content delivery, student support, and assessing individual students. Who would do this then?

The need for full-time teaching professors

I am arguing the need for a new classification of faculty, full-time teachers who have no research responsibilities. They would be full-time and permanent, have the same salaries as at least junior tenured research professors, and a progressive career structure, from novice, the experienced, to senior (where they would take on the same teaching roles as tenured research professors), as well as pensions. This classification of faculty would completely replace adjunct faculty (from whose ranks many of these full-time teaching professors would be drawn). They would work under the supervision of a tenured research professor, but would undertake most of the student support activities and student assessment. Full-time teaching faculty would have at least double the teaching load than tenured research faculty at present. However, using modern learning design and technology, we would need far fewer full-time teaching professors than adjunct faculty, and in the long term, fewer tenured research faculty.

One key requirement of such full-time teaching professors is that, as well as at least a one-year post-graduate qualification in their subject discipline, they have at least one year’s post-graduate training and qualification in post-secondary teaching methods and technology. However, their teaching loads, in terms of students, would be much higher than a tenured research professor or even adjunct faculty at the moment.

Some institutions, such as the University of British Columbia, already have full-time teaching professors, but they are a small minority. Some academic departments in some institutions already use learning design, but they are few and far between. Instead of being the exception, these developments would be the rule.

Using activity-based costing, learning design, and teaching professors supporting one tenured faculty member, the aim would be to reduce the existing cost of a program by one third, while maintaining academic standards.

Collaboration on program design, development and delivery between institutions

Back in the early 2000s I was invited by the Ontario Ministry of Advanced Education to evaluate proposals for grants from Ontario universities for moving some of their courses to online delivery. For some reason, I was given all the proposals for courses in statistics from about ten different universities. I was surprised to see how common was the content to be delivered by online learning between the universities. It occurred to me that we did not need ten online courses, but just one online course that could be shared between the 10 universities. This suggestion of mine was quickly dismissed. This would not be acceptable to the universities. But why not?

In British Columbia, there are now selected open textbooks that cover all first year and most of second year programs in all of BC’s universities and colleges. If textbooks are similar between institutions, why not courses or even programs? In the 1990s, the BC universities agreed on common distance courses from each that could form a basis for the Open University of BC’s degree. Would not a regional BC university benefit from sharing a program also delivered at the University of Victoria?

Using modern learning design and technologies such as a learning management system and Zoom, it would be quite possible to design a template course that could be used across a number of institutions within the same province. The learning support and assessment could be ‘local’ or even pooled to provide greater coverage, but the design and development would be shared.

Sharing programs across institutions could be used to save a great deal of money in program costs.

What about academic research?

However, for this to be possible without major job losses (other than adjunct faculty), the amount of research done, over time, will need to be considerably reduced. I will discuss this further in my next post.

Over to you

- Do you think that using modern learning/course design, the cost of a program could be substantially reduced without losing quality or students?

- Do you think that sharing at least course design and development across several post-secondary institutions, particularly for first and second year courses, would save money? If so, what needs to be done to break down faculty or institutional resistance to this idea?

Please use the comment box at the end of this page.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

From Brian Mulligan via LinkedIn:

While I agree with the statement as expressed above that learning design and joint courses could lower costs, I disagree with what I think is the thrust of the article, that learning design is the key to lowering costs. (perhaps I have misunderstood). Scale (as in joint courses) is the key to reducing costs, and of course a key part of that, as you describe, is the use of technology to allow teaching professors to handle much larger numbers of students. However, I would suggest that Quality and Design are secondary issues. Campus education is dominated by untrained instructors leading mediocre and poor courses. At high cost. Putting these online in a simple way (even just recording the classes) without any significant design, and giving the instructor some basic training in student support tools can be a big improvement if it results in lower fees and more flexibility for the students (ask them – their eyes were opened during Covid). It requires very little investment and is fast. Industry has long shifted emphasis away from excellence by design to Continuous Improvement. Once the mediocre course is online we can use student feedback to improve it gradually.

Many thanks, Brian. Yes, your approach is another – and much quicker – way to reduce costs. As I said I don’t have all the answers -it’s the strategy to make an effort to lower costs that matters.

This seems like a reasonable suggestion and one that would be worth exploring with at least a pilot program somewhere.

I doubt that course quality would be lost – I would wager that having a full time, teaching professor would maintain or increase course quality. I always found it strange how universities assume that having post-graduate qualifications equals being a competent teacher. While I did have several wonderful university instructors, I unfortunately had more than a few who were there only because it was required of them and who definitely would not have passed an Education Methods course.

Will you convince our slowly evolving universities of this? I sure hope one of them is willing to give it a try!