Zawacki-Richter, O. and Jung, I. (2023) Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Learning Singapore: Springer

Part IV of this open textbook is on Organization, Leadership and Change, and is the first part of the Meso-level perspective. I have already reviewed Part II, on History, Theory and Research, and Part III on Global Perspectives and Internationalization

There are 11 chapters plus an introduction in Part IV, for a total of 213 pages, sufficient to be considered a book in its own right. The chapters in this part of the book are as follows:

- 28 Introduction to Organization, Leadership, and Change in ODDE, by Ross Paul

- 29 Running Distance Education at Scale, by John Daniel

- 30 Open Schools in Developing Countries, by Jyotsna Jha and Neha Ghatak

- 31 Leading in Changing Times, by Mark Brown

- 32 ODDE Strategic Positioning in the Post-COVID-19 Era, by Jenny Glennie and Ross Paul

- 33 Resilient Leadership in Time of Crisis in Distance Education Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa, by Mpine Makoe

- 34 ODDE and Debts, by Thomas Hülsmann

- 35 Institutional Partnerships and Collaborations in Online Learning, by David Porter and Kirk Perris

- 36 Marketing Online and Distance Learning, by Maxim Jean-Louis

- 37 Managing Innovation in Teaching in ODDE, by Tony Bates

- 38 Transforming Conventional Education through ODDE, by Mark Nichols

- 39 Academic Professional Development to Support Mixed Modalities, by Belinda Tynan, Carina Bossu, and Shona Leitch

Because of the book length, I am changing strategy here. I will do the review of Part IV in two parts, focusing first on reviewing the first six chapters (28-33), then in a second post reviewing the last six chapters (34-39), plus an overall review of this section of the book. As this is an open, online textbook, you can go directly to a specific chapter if this is of interest to you.

28. Introduction to Part IV, pp. 463-474

The sub-editor for this part, Ross Paul, of the University of British Columbia, Canada, has written the introduction. He writes:

This chapter ….pays particular attention to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on perceptions of ODDE, noting both the benefits of the greatly enhanced international interest in on-line learning and the negative perceptions associated with its misuse during the sudden demand for emergency remote teaching in conventional educational institutions. It envisions a blurring of distinctions between conventional and ODDE institutions with consequent opportunities for the latter… there is a unifying theme of the critical importance of institutional leadership throughout [this Part], and a concomitant focus on how leadership has to change in a rapidly evolving international context.

There was a conscious effort to represent different parts of the world in author selection while acknowledging a preponderance of writers based in Canada….There was also a deliberate effort to gain developing country perspectives on three areas of research usually dominated by western writers – leadership, open and virtual schooling, and strategic planning.

Among the most important issues identified by the authors:

- The costs of higher education, with governments the world over cutting budgets and leaving institutions to find their own economies (Hülsmann)

- Pressures for institutional diversification to provide more equitable opportunities for access and success to all, regardless of race, gender, economic, or social standing (Jha & Ghatak)

- Pressures for graduates to be well prepared for occupational success in the knowledge economy (Bates).

- Grappling with the challenges of addressing all three components of the iron triangle of educational provision – cost, access, and quality (Daniel; Glennie & Paul).

Much is written about the need for “transformative” change in our postsecondary institutions but Nichols suggests this term is overused and that much of the achieved or envisioned change does little to alter predominant institutional structures and processes. Resistance to change is as common in ODDE institutions as it is in more conventional universities. As Brown emphasizes, higher education is “entangled with a complex constellation of change forces” and such change is difficult, requiring knowledgeable leaders with unique skill sets and, often, courage.

Paul offers some lessons learned from ODDE experiences over the last 50 years in terms of:

- accessibility

- marketing

- cost

- quality

- professional development

- strategic planning

- partnerships

- innovation.

He concludes by discussing the implications of these developments, particularly a loss of trust, for institutions and government, and makes six predictions based on the chapters in this section.

Paul has done more than just summarise the different authors’ contributions. He has placed them in an overarching framework that identifies the key developments in ODDE organization, leadership and change and their impact on the rest of the system. This chapter should be required reading for all institutional and government leaders.

Chapter-by-chapter synopsis

29. Running Distance Education at Scale, pp. 475-492

This chapter, by John Daniel, of the Acsenda School of Management, Vancouver, Canada, describes how open distance learning can be conducted at scale through open universities, open schools, and MOOCs, which are all designed to cope with mass demand, [with a focus on] institutional design and organization, governance, management and administration, and leadership….we must first ask whether specialized institutions that conduct distance education at scale are still needed. Distance education at scale is necessary because a growing number of people worldwide, numbering in the hundreds of millions, have no access to the education and training that might help them lead more fulfilling lives. We examine three areas of need:

- post-secondary education,

- secondary schooling for the hard to reach, and

- new skills and knowledge for coping with the post-pandemic world.

Daniel notes that the UN estimates that in 2030 over 200 million children will still be out of school and Daniel examines how open schools operating at scale can help to address this challenge. Daniel also notes that global higher education enrollments will grow from 250 million in 2020 to nearly 600 million in 2040: However rapidly campus institutions grow in response, it seems inevitable that distance learning at scale will be a large part of the solution. Daniel also notes that MOOCs provide post-compulsory continuing education at scale (there were 180 million MOOC participants world-wide in 2020). He then looks at how open universities, open schools, and MOOCs are able to scale up for these underserved markets, by examining two key aspects that enable them to operate at scale, and how these ODDE institutions differ from conventional campus-based institutions:

- governance, management and administration: Daniel argues that while the governance of open schools, OUs and MOOCs are quite different from each other, their management and administration are very similar, each depending on three legs of a stool:

- administration/logistics (including heavy dependence on IT);

- course materials development; and

- student support;

- leadership: five key qualities of ODDE leaders are suggested:

- a conviction that the institution can be a catalyst for global change;

- the skills and determination to sustain excellent relations with government;

- familiarity with the administrative and bureaucratic functions of the institution;

- ability to scan the environment and anticipate the implications of technological developments

-

persuasive advocacy for new initiatives.

Daniel concludes that conventional, campus-based institutions will not be able on their own to provide equal access globally to all in education. The ability of open and distance institutions to operate at scale will be essential for achieving such goals.

30. Open schools in developing countries: virtual and open or distance and closed? pp. 493-508

This chapter, by Jyotsna Jha, and Neha Ghatak, of the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies, Bangalore, India, examines the reach and experiences of virtual and Open and Distance Learning (ODL)-based education in the context of developing countries with high socioeconomic inequalities and highly uneven access to literacy and technology, through a study of the ODL experience in India….This chapter uses the research evidence from India to argue that the success of the open and virtual education initiatives or systems at the level of school education is dependent upon the presence of a number of structural, locational, educational and technological thresholds…this chapter provides an illustrative case for understanding the limitations and potential of Open and Distance Learning (ODL)-based school education in the developing world.

The authors report that the switch to virtual learning in India during the pandemic did not work for most school students in India, due to lack of access to technology, and human factors such as poor online pedagogy and lack of training of teachers in online learning. Indeed, virtual learning during the pandemic merely widened existing inequalities between rich and poor, and males and females. The authors state: to assume that the mere availability of reliable internet connectivity and a laptop or a smart phone would ensure schooling and continued learning for all has been proven wrong in a country like India, whether examined from the perspectives of physical or social access, or viewed from the angle of pedagogy and learning.

With more than three million enrolments, India’s ODL-based schooling facilities are considered one of the largest in the world. However, the formal ODL-based education covers only 2 to 3% of the school going population in India, mainly at the senior secondary level…

[Research indicates] that ODL-based education, which also serves as an examination board, is being used largely for certification alone rather than learning. In absence of any support and mediation, it is difficult for the individual learners facing various constraints and living in remote areas to learn on their own…. the barriers to virtual schooling that have recently been exposed on the face of the pandemic have also been at play in limiting the reach of the already-existing ODL-based schooling systems.

The lack of flexibility and preparedness of the existing schooling systems was a major reason for the near failure of virtual schooling in helping children from marginalized groups access learning opportunities that otherwise should have been accessible to them.

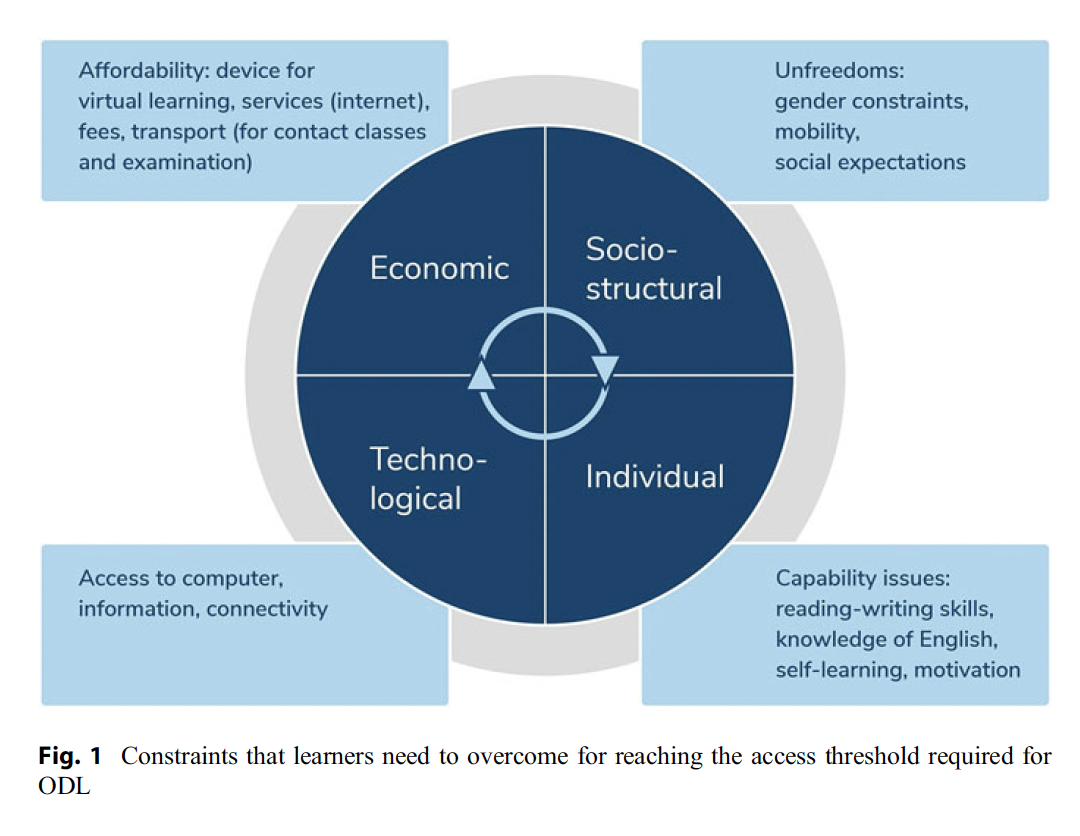

The authors then indicate three major thresholds that need to be bridged for ODL in virtual schools to be successful (see Figure 1 above):

- access

- learning support

- isystems

The authors conclude: Exclusive open or virtual schools cannot and should not replace physical schools at the school education…but open and virtual schooling practices can play a complementary role by widening the experience range of the learner in addition to its potential for certification of those who cannot or do not want to be part of the regular schooling system.

This was for me one of the most interesting and important chapters in the book. It is one of the few on open schooling, it was well researched, and has important implications for reducing inequality in education, both globally and on a massive scale.

31 Leading in Changing Times: Building a Transformative Culture, pp.509-523

This chapter, by Mark Brown, of Dublin City University, argues that digital education needs to be better understood as part of a wider social practice and transformative change agenda. Brown stresses the importance of multifocal leadership with a wide-angle lens and the ability to zoom in and out. Steering a path through many complexities, inter-dependencies, and underlying tensions without losing sight of the end destination is a key multifocal leadership quality.

Brown illustrates how the notion of multifocal leadership has been influential in a range of digital learning innovations at Dublin City University, which has established itself as the primary digital learning institute in Ireland. He gives examples of how DCU has implemented digital transformation within the institution over the last few years

Brown argues that forging a future-focused mission based on multifocal criticality and transformative leadership is not something for the faint-hearted; it requires agency, relational capital, and strategic foresight to move from digital in part to digital at the heart of your organizational culture.

Mark Brown writes well with some striking metaphors. It is hard to disagree that bringing about transformational change in higher education is a tough and complex endeavour. However, there was a certain amount of chest-thumping in the way this chapter was written that I found a little off-putting, but that should not distract from the very real achievements of DCU in its attempts at transforming the institution.

32 ODDE Strategic Positioning in the Post-Covid Era, pp. 527-546

This chapter, by Jennie Glennie of SAIDE, South Africa, and Ross Paul, of the University of British Columbia, Canada, considers some of the challenges of the development of strategy, both for the conventional and ODDE sectors of higher education. The chapter discusses the challenges for ODDE strategy development in the particular context of COVID-19 [and] concludes with implications from the analysis for both the conventional and ODDE sectors in higher education in South Africa and elsewhere based, in part, on the lessons learned during the pandemic.

They note: The pandemic has challenged the very nature of planning by forcing institutions and their leaders to “pivot” frequently to cope with the latest crisis….At a time when the majority of the population is looking to government(s) for leadership, a roller coaster of stop-go decisions has contributed to an undermining of public confidence in their leaders…..The ensuing distrust of leadership has implications for institutional leaders as well.

The first half of the chapter is an excellent analysis of the pros and cons of strategic planning in HE institutions.

The second half of the chapter is a case study of strategic planning for ODDE at a national level, the country in question being South Africa, and the role of SAIDE (South African Institute of Distance Education). The authors note that South Africa cannot afford to fund its target enrolment rate of 1.62 million students by 2030, set in 2012. ….Already staff-student ratios have deteriorated, resulting in class sizes growing dramatically in some faculties….This and the Covid pandemic underline the need for a complete rethinking of ODDE and serious considerations of new opportunities that are identified in the process.

The authors note that ODDE in South Africa has considerably increased access, especially for African students and women and is substantially more “cost-efficient” than that of the conventional institutional provision, with government subsidies per full-time equivalent student enrolment in distance education being half that of the subsidy for face-to-face provision…but Unfortunately, the third side of the iron triangle – quality – is questionable in much distance provision.

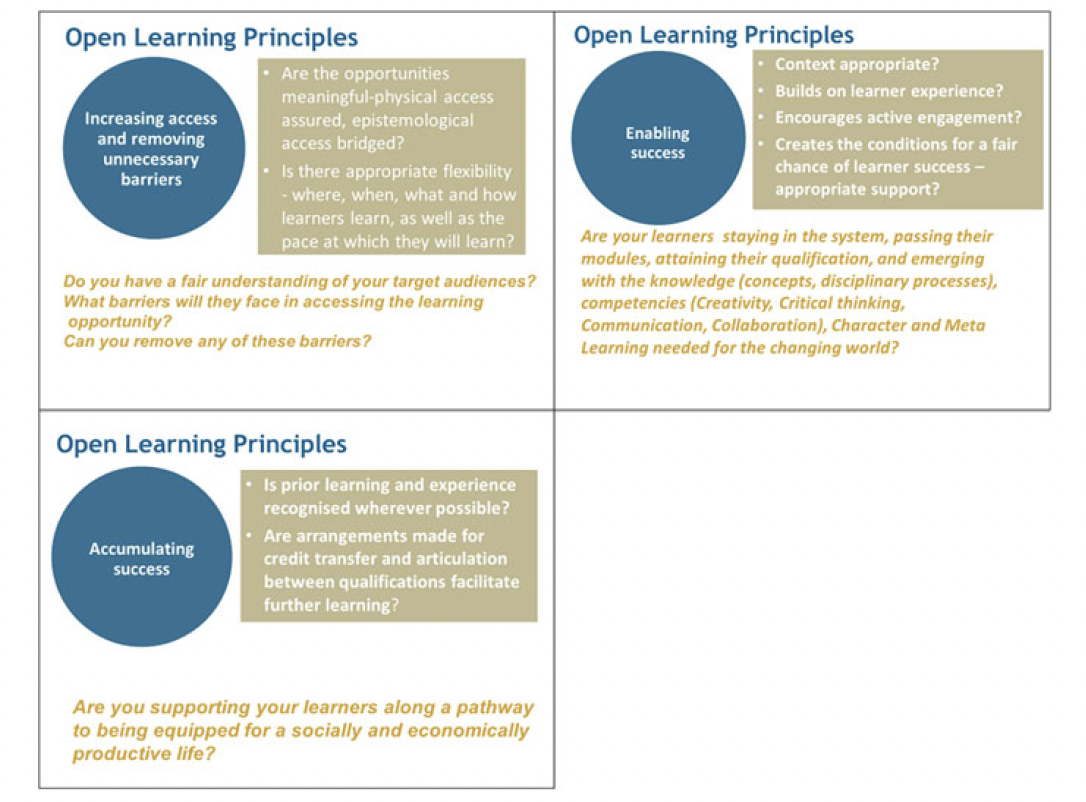

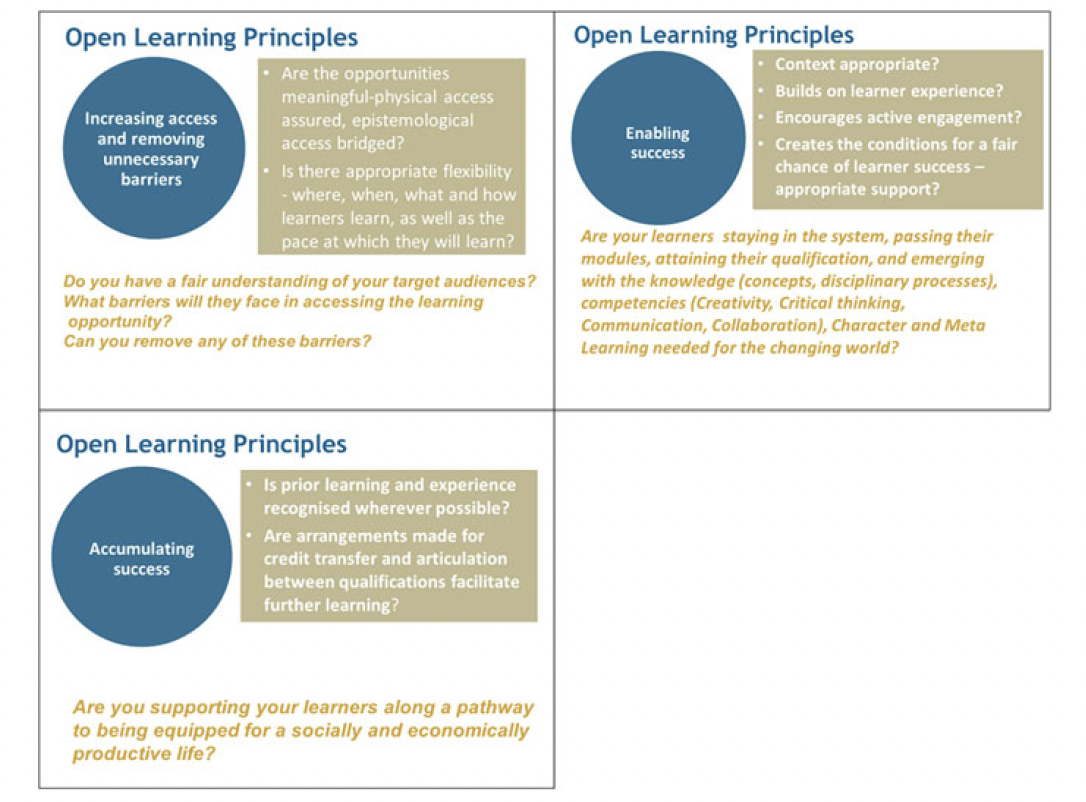

The authors then suggest that open learning principles are a useful high-level lens through which to begin to examine the quality of provision, especially for distance education. As set out in the [government] white paper of 2014, this involves careful consideration of the context in which students will study and subjecting the use of the new tools to careful scrutiny through a range of principles. These principles are then described (see graphic above).

Next the article looks at institutional strategies: COVID-19 has blown traditional higher education demarcation wide open and both traditional and ODDE institutions will need to reconsider their overall strategies in response, particularly in terms of remote and part time students, understanding the context and profile of targeted students, and cost-effectiveness.

Among other conclusions, the authors argue that ODDE institutions have dramatically increased access to higher education but unless they are able to achieve much more competitive completion rates while retaining their cost-efficiencies, they will not be seen as cost-effective recipients for the allocation of scarce national resources.

Although the case-study is specific to South Africa, much of the authors’ analysis will apply equally to many other countries, both developed and developing.

33. Resilient Leadership in Time of Crisis in Distance Education Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa, pp. 547-561

The focus of this chapter, by Mpine Makoe of UNISA, South Africa, is on the character of a distance education leader who is exhibiting personality traits that will enable him or her to move a distance education institution forward….The aim of this chapter is to illustrate the academic leader’s personality traits that are useful in managing change in times of crisis.

Because of the pandemic, Almost overnight, education ministries and academic leaders had to make quick decision to pivot to online learning. Virtually every education institution in sub-Saharan Africa struggled with this transition mainly due to the lack of the requisite information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, inadequate expertise for online pedagogies, and inability to provide appropriate devices to their students and staff. Leading change of this magnitude require[s] resilient leaders who “have the ability to recover, learn from and grow stronger in the face of adversity”.

Makoe discusses why education policies failed in the new independent countries following de-colonization in sub-Saharan Africa. As a result major changes are needed to move from the past and present to the future. Makoe argues in particular for distance education leaders with resilience: adaptive challenges facing distance education will demand resiliency, because setbacks and mistakes will be made; yet, there is a need to move forward…there is a need for leadership programs that will equip academic leaders with skills and knowledge on how to navigate jerky and shifting environments in distance learning.

Conclusion

I found this part of the book the most interesting and most stimulating so far.

The introduction to Part IV provides a framework for identifying the key developments in ODDE organization, leadership and change and their impact on the rest of the system.

There was very thoughtful analyses of the leadership and organizational challenges of ODDE in sub-Saharan Africa and India, and good coverage of the strengths, weaknesses and importance of open schools.

Several authors emphasised the potential of ODDE for meeting the challenge of access for the millions that need – and will need – secondary and higher education in much of the world, but also the need for ODDE to improve, particularly with respect to quality and student success, if equitable access to all is to be achieved.

There were also thoughtful analyses and case studies of the strength and weaknesses of strategic planning and the importance of leadership in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world following Covid-19.

I look forward to reading the next six chapters in this Part.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.