Anadolu University

Anadolu University in Turkey is nominated by the Turkish Higher Degree Act of 1981 as the national provider of distance education. Enrollment in open education programs at Anadolu University has increased from under 30,000 in 1982-83 to over 3,000,000 in 2018-19 (Bozkurt, 2019), and its programs are now also available to Turkish communities in Northern Cyprus and the European Union. This makes it one of the largest university systems in the world. It was founded in 1982 and 2022 is its 40th anniversary.

Open universities post-Covid

I was honoured to be asked to make a presentation on March 24 on the future of open universities as part of Anadolu University’s 40th anniversary celebrations. I made a formal presentation broken up with questions and input from the audience. You can see a 55 minute video recording of the session by clicking on the banner image above, but here is a condensed version of my thoughts on this topic, with the evidence to back up most of my statements.

Am I qualified?

I have some trepidation in prognosticating on the future of open universities. I was a founding staff member of the UK Open University in 1969 and worked there for its first 20 years, and was a part-time faculty member at the Open University of Catalonia for another five years and I have also experience in working with Universidade Aberta in Portugal.

However, I have worked elsewhere in the last 30 years, mainly in ‘dual-mode’ institutions such as the University of British Columbia and polytechnics such as the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology and the British Columbia Institute of Technology, so I don’t feel particularly up-to-date on open universities today. More importantly, I’m not sure what I could say that the participants, mainly Anadolu open university faculty and graduate students, did not know already.

However, having experience of a wide range of institutions does enable me to see open universities in a broader context, so here goes.

The market for open universities pre- and post-Covid

Up to the start of Covid in early 2020, online and distance learning, at least in North America, was steadily growing at a rate of about 10% per annum in student enrolments and had been for over 10 years (Seaman et al., 2018). By 2019, half of all post-secondary students in the USA were taking at least one distance education course (Hill, 2021), and in Canada, 93% of all its universities were offering at least some online courses, as were most two-year vocational colleges (Johnson, 2019).

This was seriously impacting Canada’s open universities. Université Laval, a francophone campus-based university in Québec, in 2018 had more online course enrolments than Athabasca University, the self-designated open university of Canada, and about four times the enrolments of Québec’s francophone open university, Téluq. While campus-based online course enrolments were increasing, enrolments at Athabasca and Téluq were static or declining. Distance education or online learning are no longer unique characteristics of open universities.

Furthermore, Canada and the USA now have high rates of participation in regular universities and colleges. For instance, 78% of all people in the 20-25 age brackets in Canada are taking some form of post-secondary education (Usher, 2021). (The equivalent figures for the USA is 87% and for the UK 62%). In essence, this means that most people in North America who want tertiary education can get it, helped by government grants and loans, or by scholarships from institutional endowment funds. Admission for most students to some form of post-secondary education is no longer a barrier in most countries in the Global North. (Getting into the university of one’s choice is another matter.)

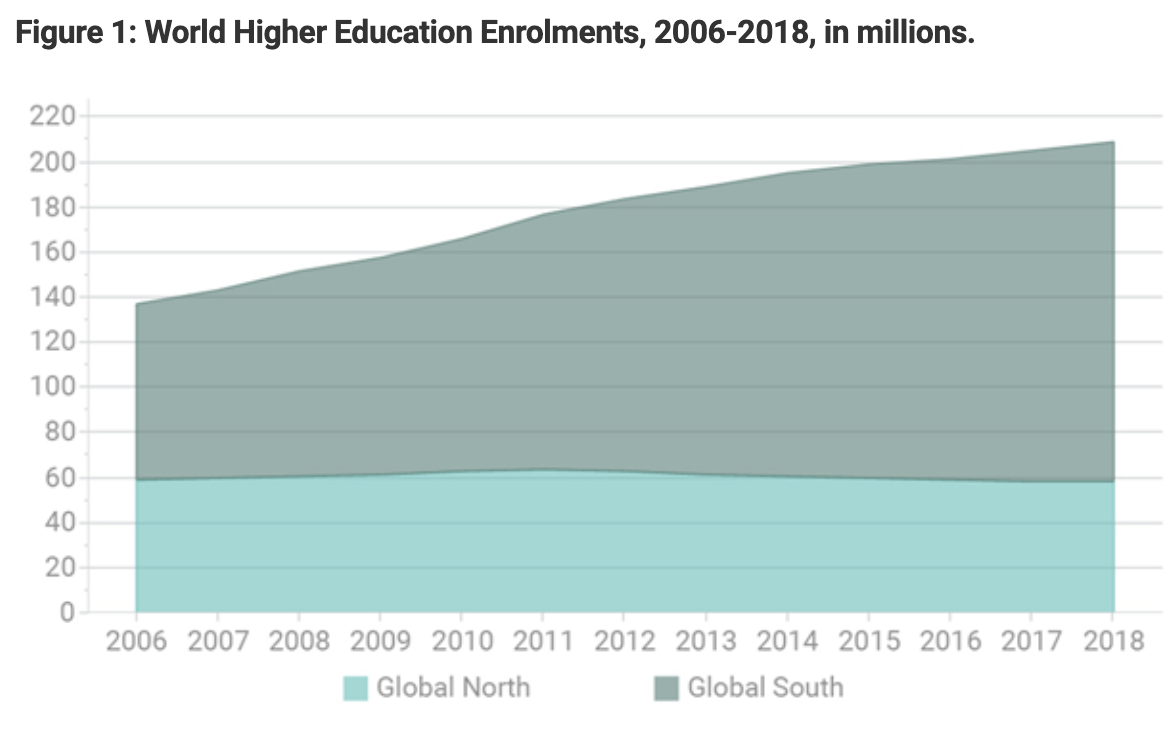

While, in the Global North, admission to tertiary education is nearing saturation, in terms of overall enrollment growth, the situation in the Global South is different. As Usher reports (2022) ‘in the North, total enrolments have fallen, partly due to demographic factors in Eastern Europe and Russia, and partly due to the fall in short-cycle enrolments in the United States. But the South has seen consistent growth. In 2006 the region has 80 million students; in 2018 it had approximately 150 million.’

So even in the Global South, access to tertiary higher education has rapidly improved over recent years, although in many countries higher education participation rates still have a long way to go to match those in the Global North. There is probably still plenty of room for large-scale open universities in these countries, but in the long-term, countries in the Global South are likely eventually to get close to the participation rates of the Global North. This means that open universities will increasingly be competing for the same students as regular universities, if they are not already.

Post-Covid, the competition for online students is likely to increase. In most countries, nearly all universities have some experience now of at least emergency remote learning. This has had several effects that could impact on the market for open universities:

- the quality of online learning in dual-mode institutions in Canada was already high before Covid-19, with sophisticated online course design and high completion rates (see Ontario, 2011)

- many more campus-based institutions will be offering online distance courses post-Covid

- a great deal of faculty development occurred during Covid, helping instructors to move their courses online; this will lead to an increase in the quality of online teaching within conventional universities moving into online learning after Covid

- there will be a big expansion of blended or hybrid learning, where instructors deliberately mix in-person with online learning, giving more flexibility for students

Technology access is a major problem for many students

Even in technologically advanced countries such as Canada and the USA, a minimum of 25% of the population do not have technology access adequate for online study. The figures for less economically developed countries are likely to be much higher.

This is lack of access is due to several reasons:

- lack of adequate Internet access (10-25mbs), especially in rural/remote areas. In Canada in 2021, 15% of homes had no Internet access or had access at less than 10mbs (dial-up service), according to the federal Canadian Radio and Television Commission

- being poor, unable to afford either computer equipment and/or the rates for Internet service

- crowded accommodation with multiple users sharing inadequate bandwidth (a particular problem with Zoom or other video streaming, which takes three times the bandwidth of a learning management system).

However, these are just the kind of students that open universities might be expected to serve. It thus raises the question of if or when open universities should use online learning, or what they should use instead, such as print or broadcasting. However, given the need even or especially in less economically advanced countries for digital literacy and training in 21st century skills for economic development, this is a tough question. It may be necessary for open universities to support specifically better access to technology, through local learning centres, equipment loans, or targeted fee reductions, to ensure all their students have appropriate technology access.

Re-examining the purpose of open universities

These issues raise questions about the function and purpose of open universities. Are they still relevant? If so, what are – or should be – their unique features, their unique selling point in an increasingly crowded market?

To answer this question, I am looking backwards as well as forwards. I was fortunate to be present in the Guildhall in London in 1969 when Lord Crowther, the Chancellor of the UK Open University, gave the inaugural speech. It was mercifully short (12 minutes), to the point, and above all inspirational (you can listen to it here). I was particularly struck by Crowther’s interpretation of ‘open’, the four characteristics of which seem as relevant today as they did 60 years ago.

1. Open to people

Crowther talks of tapping the ‘great unused reservoir of human talent and potential’. This was particularly relevant in Britain where only eight per cent of school leavers in 1969 went on to university. With the figure now standing at 62%, there is still room to go, but now the market is not so much school leavers who cannot get into university or college from school, but those who, for whatever reason, missed out in higher education after leaving school, or, after university or college, find they need further knowledge or qualifications.

Furthermore although many universities and colleges are now using online learning or distance education, you still need minimal qualifications (using high school completion or an entrance exam) for admission. Walter Perry, the first Vice-Chancellor (President) of the the UK Open University said: ‘We don’t care about your qualifications coming in; it’s what you can do when you graduate that counts.’ As Crowther said, referencing the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour,:

- Give me your tired, your poor

- Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free

- Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me:

- I lift my lamp beside the open door.

That lack of barriers to admission to me reflects a potential unique selling point for open universities, but few these days are brave enough to accept this challenge. But why not ‘a university for the homeless and tempest tossed’? For instance, 2U is working with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine to offer all Ukrainian colleges and universities free access to edX Online Campus for the foreseeable future. This will enable evacuated Ukrainians to continue their studies (unless the Ukrainian universities already have online programs, which they may well do.)

Open access will also mean providing a much wider range of student support services than conventional universities, and working closely with non-governmental organisations, community support groups, and other basic education providers to ensure students succeed, whatever their circumstances. Many of these arguments are set out in Walter Perry’s personal account of the establishment of the Open University, which for many years had a very successful, completely open access admissions policy.

2. Open to places

Crowther:

This University has no cloisters – a word meaning closed. We have no courts – or spaces enclosed by buildings. Hardly even shall we have a campus.

The original idea for the UK Open University was a ‘University of the Air’, based largely on broadcasting. This changed over time, but the fundamental concept remains. Open learning should be available universally, through the Internet or whatever other channels of mass communication are themselves truly open, wherever and whenever a learner wants to access it. Also, it is not just place, but also time, that needs to be open, which suggests asynchronous learning, flexible delivery and ‘on-demand’ assessment.

3. Open to methods

Crowther: Every new form of human communication will be examined to see how it can be used to raise and broaden the level of human understanding. Crowther commented: the addiction of the traditional university to the lecture room, is a sign of its inability to adjust to the invention of the printing press.

This suggests to me that open universities need to be on the leading edge in the exploration and use of new technologies for teaching, such as, today, simulations and games, augmented and virtual reality, and artificial intelligence. In turn, open universities’ addiction to print is a sign of their inability to adjust to the Internet. The challenge today is to combine the benefits and avoid the limitations of synchronous and asynchronous methods of online learning. We need more agile and cost-effective methods of course design that ensure quality in online learning. This may mean developing quality standards for synchronous as well as asynchronous online learning.

4. Open to ideas

This is probably the least remembered but the most important of all the four ‘opens’, especially today. Crowther said we should regard the human mind rather as a fire that has to be set alight rather than as a vessel, of varying capacity, into which is to be poured as much as it will hold of the knowledge and experience by which human Society lives and moves.

Especially in increasingly authoritarian countries, open universities need to be brave, by challenging fake news, state propaganda, and fostering new ideas and innovation. This will mean becoming internationally focused and supported by external partnerships and alliances, such as ICDE and EDEN, and in establishing locally engaging online communities of learning and practice.

Although all four of Crowther’s conception of open apply just as well today, I would add a fifth.

5. Open to resources

Open universities should be the leaders in developing and promoting open educational resources. Furthermore, with so many other suppliers of OER, open universities should focus on two aspects of OER:

- cultural and language relevance (i.e. OER in Turkish)

- high quality in both content and production.

It is important to make the point that OER are very important and valuable, but they are just one and not the most important aspect of open in education.

Conclusions

- Open universities are and will continue to face increasing competition for students from more conventional universities and even more so from external competitors such as private and commercial organisations, especially the large tech giants.

- For many conventional universities, quality in online learning is still a major challenge, particularly those that came new to online learning during Covid. Open universities will need to have the most agile cost-effective and high quality online courses to compete successfully.

- As well as quality of courses, open universities need to focus on increasing access to higher education for those currently not served. This will mean high levels of student support and partnership with other organisations.

- Open universities will need to constantly re-invent themselves to survive in a fast-changing and challenging external environment. This will require nimbleness and constant innovation.

- Congratulations on Anadolu University on its 40th anniversary and here’s to the next 40 glorious years!

Questions

I asked the following questions of participants during the presentation:

In Turkey:

- Are campus-based universities moving more into online and distance learning (after Covid)?

- Are there other competitors, e.g. private online learning companies?

- Are campus-based universities in Turkey moving to blended learning?

- Has the acceptance of online learning increased or decreased because of emergency remote learning?

- how will this impact on Anadolu University’s market for students?

At Anadolu University:

- Do you have many online courses?

- Is Internet and equipment access an issue?

- Why is it important to offer online courses?

- Is there a strategy for online and digital learning in the future?

- Do these four/five elements of open-ness (people, space, methods, ideas, resources) also apply to Anadolu? Are there OTHER aspects of open that Anadolu should pursue?

- What directions should Anadolu take in the future that is different from now? (Course design, type of students, technologies, etc.)

You can hear some of the questions and comments from Anadolu participants on the video recording, moderated by Professor Aras Bozkurt of Anadolu University.

References

Bozkurt, A. (2019) The Historical Development and Adaptation of Open Universities in Turkish Context: Case of Anadolu University as a Giga University IRRODL, Vol. 20, No. 4

Hill, P. (2021) Alternative View: More than 50% of US Higher Ed students took at least one online course in 2019-20 PhilonEDTech, October 7

Ontario (2011) Fact Sheet Summary of Ontario eLearning Surveys of Publicly Assisted PSE Institutions Toronto: Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities

Perry, W. (1976) Open University Milton Keynes: Open University Press

Seaman, J. et al. (2018) Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States Babson Survey Research Group

Usher, A., (2021). The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Higher Education Strategy Associates

Usher, A. (2022) The Rise – and dilemma – of the Global South Higher Education Strategy Associates, March 15

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.