Getting ready for the fall

In many countries, including Canada, it is expected that most people will be vaccinated by September. Thus many students are hoping for a return to ‘normal’ campus-based teaching for the fall semester and many universities and colleges are now expressing optimism about a return to campus-based teaching. However, there is still a way to go before the fall semester, new variants may increase, and not everyone may choose to be vaccinated. Nevertheless, research in 2020 showed that universities that made early decisions (by the end of May) did better in preparing for the fall semester, even if they had to adjust nearer the time, than those that left decisions until late summer.

Last week I saw a report that most Canadian universities are planning for students to return to campus in the fall – except for the large lecture classes. Both UBC and McGill announced that the large first year lecture classes may still be delivered online. Queen’s University said it expects most large classes will still be delivered remotely if COVID-19 restrictions remain in place throughout the fall. The University of Ottawa has told students that ‘we are equipping all our classrooms with educational technology that will allow for simultaneous in-person and videoconference teaching.’ At the University of Toronto ‘we are optimistic that most courses, student services and co-curricular activities will be able to proceed in person, with the possible exception of large-scale gatherings.’

The issue

If it is still necessary to avoid the large in-person lecture class in the fall, what are the options?

The simplest is to continue to deliver regular lectures by video-conferencing, such as Zoom. However, we know that this is not a good solution for many students:

- It is the first year students who tend to get most of the large lectures. However, they are the students who most want – and need – the campus experience. In particular, they want the social and cultural aspects of an on-campus education. Sitting at home instead of being on campus will be bitterly disappointing for them.

- We also know from research that first year students tend to be less independent learners, needing more help and support from instructors and other students as they transition from schools to post-secondary institutions.

- A third reason – based on research that goes back as far as the 1960s – is that the regular, long (60 minute or more) lecture, even in-person, is not an effective way to teach

- It is even less effective for students studying online, in isolation, partly because of cognitive overload, and partly because of the lack of interaction within the class with either instructor or other students.

- Lastly, much of what is taught in first year lectures often covers similar content to that in the first year textbooks. Both focus on content transmission. Increasingly, though, in a digital age greater emphasis needs to be given to the development of higher order ‘soft’ or intellectual skills such as critical thinking, independent learning, knowledge management, and communication. Lectures are not the best method for developing such skills. The time of a well qualified subject expert would be better spent in helping students to develop such skills within their subject area, and in supporting students’ learning from the textbook and increasingly from other online resources.

I am therefore arguing that now is the time to give some thought about the best way to design and teach large lecture classes online for next fall. I set out some options below:

1. Just don’t do it

‘It’ is the regular one hour or more lecture to 100 students or more, three hours a week, 13 weeks a semester.

Why do we lump together large numbers of novice learners and keep small classes for graduate students, and undergraduate students in their last year? This is not based on research on student needs, but on administrative and instructor preferences.

One way to avoid the large lecture class would be to re-distribute teaching loads. In general, in Canadian post-secondary education, there is one instructor for every 20 students (2 million students/100,000 instructors.) The ratio is slightly higher in colleges and slightly lower in universities.

There are all kinds of reasons why this ratio is not applied to teaching: instructors teaching more than one course; sabbaticals; senior professors not wanting to teach ‘boring’ first year subjects; faculty who concentrate solely on research; the use of contract or adjunct instructors; and the sheer availability of large numbers of large lecture theatres. However, even allowing for these factors, there is no ‘supply’ reason why the average class size should not be around 30-50 students per instructor, including first year classes.

Certainly, it would not hurt to try to reduce the average class size in first year (some institutions cynically cap the class at 199 students because of the negative effect of 200+ on world university rankings.) This would also allow for more effective teaching methods that enable greater interaction between instructors and students. This would lead to higher completion/continuation after first year and help keep overall enrolments up at a time when domestic enrolment is stagnant or declining.

I am not arguing against the occasional, focused lecture. For instance:

- a good overview of the course, an introduction to the main issues, and the instructor’s expectations of students, in terms of work and learning outcomes, is a good way to kick off a course.

- Similarly, a lecture near the end of the semester to summarise the issues, to provide indicators of possible exam topics, and above all to offer a chance for students to raise questions and issues that they are still struggling, with, will also be valuable.

- Maybe also a lecture in the middle of the course that looks at progress to date, allows for students’ questions about the course as a whole, and an indicator of what’s still to come, will also have value.

The rest of the course, though, could be organised differently, in ways I will discuss below.

However, the large lecture class is not going to go away by September, because there are just too many barriers to remove, although now is as good as any time to start thinking about alternatives.

2. Knowledge management versus content presentation

First year instructors spend most of their time preparing and delivering lectures and testing students on their knowledge. (If they are fortunate enough to teach subjects with a heavy focus on learning facts, concepts or principles, even the testing may be automated).

However, as I have already pointed out, most content is already available to students in the form of textbooks. Increasingly, these textbooks are online, free (open) and come with a good deal of supporting material such as web sites with exercises and online tests. In addition, many journals are now available online and are often open, i.e. access is free, or available online through the institution’s library. Lastly, there is a great deal of relevant but non-academic information generally available through the Internet, which used properly, can be a rich source of material for learning. Basically nearly all content is increasingly open, free, and downloadable from the Internet.

So what is the added value of the lectures? In later years it may well be new or unique research that the instructor is doing, or can draw from, that is not easily available to the students, but in first year that is rarely the case.

When an instructor prepares a lecture, at least in first year, they are often doing work that the students could be doing: searching for information, raising issues, making a strong case or argument, coming to conclusions. These are skills that students increasingly need to develop themselves.

This changes the role of the subject expert. They still need to decide what is important for students to learn, but more importantly instructors also need to

- guide students to where they could find relevant information,

- provide guidance or criteria for assessing the value or reliability of the information

- assist students in applying that information to various problems or approaches,

- help students to build an evidence-supported or logical argument

- assess how well the students have developed the skill of knowledge management and its application.

Much of this could be done (once) through the learning management system rather than lectures (repeated annually). Rather then than spending a great deal of time preparing and delivering lectures, instructors could spend that time in supporting students in their learning. This is especially important in students’ first year studies, because it builds the foundation for more independent study in later years.

Note that the switch from content acquisition to knowledge management is an issue not just for large online lectures, but for all large lecture classes. However, because students can go online and do much of this work, online learning lends itself to this kind of approach. The issue then is not online or in-person lectures, but the management of very large classes, where this approach demands a different input from the instructor but which can be very demanding of the instructor’s time (which is why again the best solution is to reduce first year class sizes).

So how can this approach work with very large online classes?

3. Peer-to-peer learning

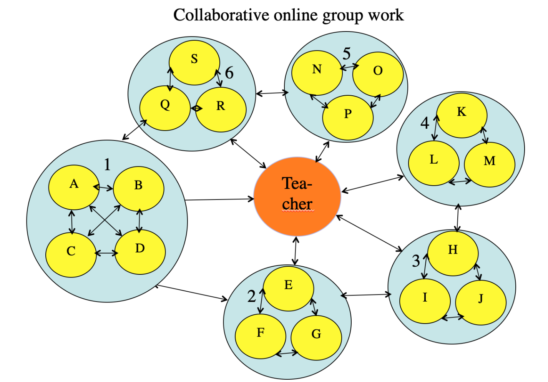

One of the biggest student criticisms of emergency remote learning has been the loss of a sense of community. Students were studying online in isolation, not in groups. However, there is absolutely no reason why students cannot study effectively in groups online. Indeed there are clear guidelines on this.

Prior to Covid-19, a great deal of research was done on online communities of inquiry, which emphasise the importance for student motivation of collective online activities. Students learn more deeply by testing ideas and working with each other than they do by working in isolation.

There are two technical ways to do this. The first is through asynchronous online discussion forums, or asynchronous online projects, using the learning management system. The second is through synchronous break-out rooms in a video-conferencing system such as Zoom.

However, synchronous break-out sessions in Zoom become a nightmare with a very large lecture class. You would need many different groups working in parallel. Asynchronous online groups though with a learning management system are more manageable for very large classes. Groups can be larger and still effective, students can spread out their work over the week, and the group work is easier for the instructor to monitor online.

Nevertheless, synchronous groups are a good way to open a discussion – students can see each other, goals can be set, and ways of working as a group can be discussed – which can then move to asynchronous discussion. Again, though, this needs planning and some experience on the part of the instructor to manage.

But getting students to work together online is not only a useful experience in itself (as we have all discovered during the pandemic), but enables more time on task by students and also provides reinforcement or challenging of concepts. More importantly it spreads the instructors’ work load. Monitoring 20 groups is a lot more manageable than monitoring 200 individuals. But this will mean trading time that would otherwise be spent on lectures for time supporting the different groups.

4. Keep your online lectures short, with activities

If students can access most content online, what is the most useful thing you can do as an instructor when talking to 200 students or more online?

Generally, students studying online in isolation work in small chunks of time, usually no more than an hour, without interruption (family, cat, phone calls, shopping, on the bus, even driving, listening to podcasts). Also, research shows that attention starts to drift after 15 minutes or so.

So keep your videos relatively short, preferably to 15-20 minutes, allowing time for follow-up activities by the students. Students need to be active for them to reinforce what they have learned immediately following the lecture. It could be as simple as asking them to organise their notes, but more likely it will be to do some follow-up work. This will probably mean reducing considerably the amount of content you deliver through lectures compared to a regular on campus class, but then students can go online for details, or for more content not covered in the videos.

So you are probably going to focus on the big picture: what are the main ideas or challenges in the field? What further research on the topic could students do on their own? What are the really difficult concepts that you could help all students with? So you need to be really focused. (For an example from my own work, see the 12 x 10 minute videos I made for my book, Teaching in a Digital Age.)

Also, don’t start with the lecture when planning the week’s work for students. Use the learning management system for instructions and activities for the students. But remember that for a three credit course, students will likely have just eight hours a week at the most for all their activities related to the course, including assignments, group discussion, watching video, and reading. Thus it is to the learning management system that students should go first, and the ‘lecture’ needs to fit within all the other activities – hence the need to focus on what you can do best to help students within a relatively short lecture presentation.

5. Assessment

Oh, boy! This is probably the main challenge of large lecture classes, whether delivered in person or online. How do you assess deep learning with a class of 200 or more? Sure, you can test memory or even basic understanding with multiple choice tests (again, either in an exam room or online), but how about the more important 21st century skills of creativity, critical thinking, analysis, problem-solving, etc? Yes, you can assess such skills but that usually takes much more time than just testing memory or even understanding. Or do we not want first years students to start developing such complex skills? This is not an issue of online vs face-to-face but of sheer numbers, another reason for avoiding such large classes in the first place.

But given that we have such large classes and they are being taught online, what is the best way to assess students? Certainly not through intrusive monitoring with cameras in homes to replace the not so efficient human monitoring in a crowded exam room.

Again, assessment online comes down to your method of teaching. If the focus is on content transmission, then online testing of memory or understanding will be similar, if not so easy to monitor, as in-person testing under supervision.

But if the focus is on embedding the lecture within an overall approach of helping students to develop skills such as knowledge management, communication, and critical thinking, online learning leaves a continuous and permanent trace in the online responses and interactions of students. You can see how they are developing by observing their online activity within the course.

This means of course authentic and continuous assessment, rather than an end of course summative exam (although it may be wise to combine the two.) It also means being vigilant as an instructor, spending time monitoring student online activity and indeed often intervening and giving feedback, not to every student but enough for all students to benefit – and to appreciate that you are there for them.

Conclusion

There are no easy answers to the issue of making large lecture classes effective, whether online or in-person. Lectures have the in-built advantage of economies of scale, but as with all mass production it leaves little room for variability in learning, and limits the focus of what students can learn in that environment.

It is though really important to understand that the context for learning is quite different for an online lecture. The student is alone and isolated. Creative measures need to be taken to break down that isolation, such as group work and some sense of control over their own learning, through activities and follow-up work.

I am particularly concerned about the problems with splitting the same synchronous class into two groups, those taking the course in-person on campus, and those taking it in isolation at home. This can work if it is the student’s choice to take the class at home and if great care is taken by the instructor to include external students within the overall lecture, but if the class is arbitrarily divided into on-campus and online, we know from research that the students taking the online component can easily be frustrated and feel excluded. (For some good advice on how to handle this situation, see: Teaching Dual Audiences from the University of Southern Florida’s Academy for Teaching and Learning Excellence).

Without substantial re-design, moving large lectures online will increase the workload and stress on instructors, and/or will lead to poorer results for students. So now is the time for administrators and Deans to start asking whether we should be moving the large lecture classes online, or instead, finding better ways to deal with first year courses.

If though there is any likelihood of continuing large lecture classes online in the fall, now is also the time for instructors to start thinking about the design of such classes, to make them more interactive and more effective. I wish you all the best of luck with such a daunting challenge.

Resources and further reading

Academy for Teaching Learning and Excellence (undated) Teaching Dual Audiences Tampa FL: University of Southern Florida

Bates, T. (2019) Teaching in a Digital Age, 2nd edition Victoria BC: BCcampus (especially Chapter 4; Chapter 7)

Bligh, D. (2000) What’s the Use of Lectures? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Centre for Authentic Assessment (undated) Authentic assessment Bloomington IN: Indiana University

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Harasim, L. (2017) Learning Theory and Online Technologies 2nd edition New York/London: Taylor and Francis

Mayer, R. E. (2009) Multimedia learning (2nd ed). New York: Cambridge University Press

McCormack, M. (2020) EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Fall Readiness for Teaching and Learning, EDUCAUSE Review, September 18

OCUFA (2020) OCUFA 2020 Study: COVID-19 and the Impact on University Life and Education Toronto ON, November

Royal Bank of Canada (2018) Humans Wanted Toronto ON: Royal Bank of Canada

UBC Wiki (undated) Design Principles for Multimedia The University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC

Usher, A. (2019) Managing Class Sizes (Part1) Higher Education Strategy Associates, September 18

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.