Goldrick-Rab. S. et al. (2020) #RealCollege During the Pandemic The Hope Centre for College, Community and Justice Philadelphia: Temple University, June, pp. 22

This is the third post in a series of three about reports on the digital divide and online learning. The first was about an article from the Economist Intelligence Unit that focused primarily on the divide between institutions and countries that were prepared for digital learning and those that weren’t. The second was about a report by the online journal Inside Higher Education about technological inequity among students in the USA and some solutions.

What is the report about?

This report is quite different in that it is not specifically about emergency remote learning or online learning. I have included it though because it looks at basic needs security. Why I chose this report is because of what a former colleague of mine, a teacher in an inner city school, once said to me: ‘Children can’t learn properly if they come to school hungry or if there is trouble at home.’ If basic needs are not met, then moving courses online is unlikely to be effective; indeed any form of educational delivery is likely to fail if learners lack basic needs.

This report examines the pandemic’s impact on students, from their basic needs security to their well-being, as indicated by employment status, academic engagement, and mental health.

Who did the report?

The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice promotes a national (USA) movement centering on students’ basic needs, called #RealCollege. It argues that students’ basic needs for food, affordable housing, transportation, and childcare, and their mental health are central conditions for learning. The Hope Centre’s focus is on four pillars: action research, engagement and communication, advocacy, and sustainability. It is currently based at Temple University, Philadelphia. It was established well before Covid-19, and had conducted national student surveys in 2017,2018 and 2019.

Financial support for this survey was provided by Conagra Brands Foundation to Believe in Students, a nonprofit partner.

Methodology

The report was based on responses from 38,602 students, who responded to an online survey conducted between April 20 and May 15 of 2020 using volunteer higher education institutions. This represents a response rate of 6.7% of all those covered by the survey (approximately 575,000 students). The responses were heavily weighted by students in two year colleges (almost 80% of the responses). Community colleges in California though were not included in the survey.

Participating in the survey also required internet access and provided limited incentives to students. Consequently, those students at greatest risk of basic needs insecurity were possibly the least likely to answer the questions, potentially producing conservative estimates.

The report provides details of the exact questions asked of students.

Main findings

These are a summary of detailed findings. As always, I recommend you read the original report for greater detail.

-

58% were experiencing one or more forms of basic needs insecurity. That rate did not differ between students in two-year and four-year institutions.

-

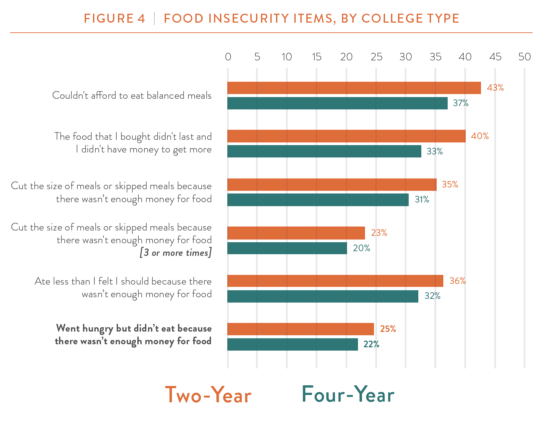

44% of students at two-year colleges and 38% of students at four-year institutions experienced food insecurity in the prior 30 days.

-

36% of students at two-year institutions and 41% of students at four-year institutions were experiencing housing insecurity:11% of students at two-year institutions and almost 15% of those at four-year institutions (4,000) were homeless when surveyed; 6% reported that they did not feel safe where they were living.

-

33% of two-year college students and 42% of four-year college students lost at least one job, while 32% of two-year college students and 28% of four-year college students experienced a reduction in hours and/or pay. Just 36% of students with jobs before the pandemic did not experience negative changes to their employment as a result of the ensuing crisis.

-

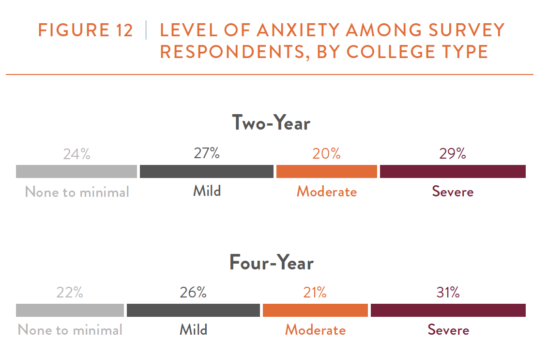

half of the respondents were experiencing at least moderate anxiety at the time they were surveyed, and around 30% were experiencing severe anxiety (see Figure 12 below)

-

Half of the respondents at two-year colleges and 63% of respondents at four-year colleges said that they could not concentrate on their schooling during the pandemic; 41% of students at two-year colleges and 36% at four-year institutions said they needed to care for family members while also going to school;

-

around one in five students said that they lacked a functional laptop or did not have reliable internet access. The former problem was less common at four-year institutions than at two-year institutions.

-

just 21% of students experiencing basic needs insecurity said that they applied for unemployment insurance; 60% said that they were ineligible for various reasons.

Report conclusions

With nearly three in five students experiencing basic needs insecurity during the pandemic, it is understandable that at least half of them also said they are having difficulty concentrating on schoolwork. Basic needs insecurity among college students was already widespread before the pandemic, and this report indicates that the rates are likely worse now. Moreover, there are stark racial/ethnic disparities that, if not remedied, will further drive inequities in college attainment.

The Hope Centre offers seven guides to addressing students’ basic needs (including advice for students), and these are listed in the report.

The report also makes five recommendations:

-

Federal and state policymakers should continue to invest in student emergency aid. Emergency aid is a critical college retention tool for supporting students who face economic shortfalls that might disrupt their education

-

Formulas for institutional appropriations at both the state and federal levels should be revised to ensure that part-time students are treated as full-time human beings.

-

The current rules… favor (or even mandate) low-wage, low-growth work over education, [so] halt federal requirements tied to work in public benefits programs, and make postsecondary education a highest priority.

-

The Department of Education should …ensure that students receiving public benefits get the maximum financial aid allowable.

-

Reduce the substantial administrative burden on higher education institutions, which is compromising their ability to address students’ basic needs.

My comments

This is a well conducted study. Although the response rate is low, it represents an uncommonly large multi-institutional student sample. This report makes it very clear that many students lack basic needs, and that as a result they experience greater stress and difficulties as students. Covid-19 increased the number of students with difficulties in this area.

Yes, this report is very specific to the USA and reflects some of the difficulties resulting from the Trump administration’s initially slow response to the pandemic. However, the general findings are likely to apply to other jurisdictions, although the numbers or proportions of students affected will vary. I would be astounded for instance if there were not many students in Canada suffering the same stress as their counterparts in the USA.

The key point here is that a lot of student dissatisfaction with emergency remote learning is underpinned by other troubles and anxieties which have been magnified during the pandemic. Education – and emergency remote learning in particular – can go only so far in mitigating the effects of basic needs not being satisfied, and students lacking basic needs will always have to struggle much more.

This has been an awful 12 months for all students, but some have clearly suffered more than others. All countries, but some more than others, still have a long way to go to ensure equal opportunities in education and other aspects of life. A return to a new ‘normal’ in post-secondary education will not resolve the underlying causes of inequality, nor help many students lacking basic needs.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.