This is the second of three posts examining the purpose of online and digital learning. In the first post I looked at the government of Ontario’s strategy to require high school students to take four of their 30 credits online.

In this post I examine Kevin Carey’s claim in the Huffington Post that online learning could dramatically reduce the cost of higher education but hasn’t done so yet because of the commercialization of online learning.

Carey’s argument

Carey’s rather lengthy essay makes basically three main points:

- today, ‘the [USA’s] best colleges are an overpriced gated community whose benefits accrue mostly to the wealthy’; the high cost of tuition is pricing the average student out of higher education

- online learning could and should radically reduce the cost of higher education, therefore making it available to all

- however, this has not happened, because HE institutions have used private, for-profit companies called online program managers (OPM’s) to develop their online programs, and the huge profits that OPMs are making prevent HE institutions from making any savings on online learning.

Now the first thing to say is that the HE system in the USA is funded very differently than the HE system here in Canada:

- in general, tuition fees are lower in Canada, mainly because provincial governments did not cut HE funding during and following the 2008 recession to the same extent as the states did to public universities in the USA;

- also in Canada we have almost no private universities, either for-profit or not-for-profit. As a result we have not had the same concerns about the impact of for-profit institutions using online learning;

- thirdly, although OPMs are common in the USA higher education system, they have had virtually no impact on Canadian universities or colleges, where online learning has almost universally been developed in-house.

Nevertheless these differences are useful as it allows some of Carey’s arguments to be checked. For instance, if OPMs are sucking all the money out of online learning in the USA, why are online courses in Canada not much cheaper than the regular campus-based programs? In general, tuition fees are nearly always the same in Canada for both on-campus and online programs. Does this mean that Canadian universities and colleges are making tons of money from online learning? Apparently not.

The cost of online learning

At least in Canada, very few institutions have gone into online learning either to save money or to make a profit or surplus from online courses. The main reason most institutions give for online learning is to increase student access and provide more flexibility for students, according to the 2018 national survey. Saving money was never mentioned.

In general, online courses are designed to cost roughly the same, in terms of teaching costs, as campus-based programs. This results in levels of teaching support being roughly the same. In other words, if there is one instructor for every 25 students on a campus-based course, there’s likely to be one for 25 students on an online course.

The main variation (as on campus) is for online courses with large numbers of enrolments, when additional, lower-paid contract or adjunct instructors will be hired. Sometimes these will be paid less and have a heavier load than a full-time instructor or professor, but this is the same for both online and campus-based courses.

Could online be cheaper?

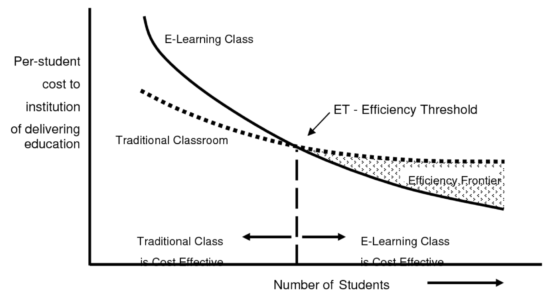

Carey’s point is that online learning should be much cheaper than campus-based teaching: no gated community, no sports fields and stadiums, no building construction or maintenance, no heating and lighting, no physical libraries or laboratories. Many of the institution’s ‘overhead’ costs are transferred to the student, who works from home (or someone else’s office).

The 2018 national survey of online learning indicates that online registrations in Canada are the equivalent of four campus based universities of 25,000 students and five colleges of 10,000. (There are roughly 70 universities and 150 public colleges throughout Canada). However, these are marginal not base cost savings. Most of those online students are also studying on-campus: they are taking a mix of campus-based and online courses. Online learning therefore does allow for some increase in enrolments overall at a lower unit cost than adding more classrooms and campus library space, but this is not large enough to radically reduce the overall cost of tuition.

The other way that online learning could bring down the cost is by automating the online courses so that once they are designed they need no or minimal human support: feedback and assessment would be provided by computer software and artificial intelligence. This is the dream (and fallacy) of those that believe online learning can dramatically reduce the cost of higher education, basically by eliminating the high cost of professors and instructors. However, at least in universities, teaching is only one part of a professor’s job; research takes at least as much of their time and they usually need physical facilities to support their research.

Even more importantly there are very strong pedagogical reasons why automating online learning, at least using current technology over the next 10 years or so, is a bad idea. We need graduates with high level intellectual skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, and inter-personal skills that cannot be effectively taught yet (if ever) by machines. Learning for most students is personal: they need encouragement and support, they need personal feedback. In other words they need a skilled, knowledgeable person to enable them to succeed. Computers and AI can help students but should not replace the personal touch.

Thinking differently

Many students (and parents) want the campus experience, at least at some time in their life, even if they have to pay for it. However, once they have spent four years on campus, many are quite happy to study further online, especially once they have a job and a family. So it’s not either on-campus or online for most students: they want both, at different points in their life.

Nevertheless, there are important lessons here for institutions and instructors:

- instead of assuming the cost will be the same for online and face-to-face teaching, could we start thinking of how we could just as effectively teach at lower cost, by gradually introducing more automation to teaching (especially regarding the delivery of content) and focusing more on humans/instructors providing stronger learning support for students? This would mean less of sage on the stage and more of guide by the side.

- could we build business models that would encourage more cost-effective teaching through the use of online learning? This could be done in a number of ways:

- graduating more students for the same cost

- graduating better students (more appropriate skills) for the same cost

- maintaining student numbers and outcomes at lower cost

- instead of of automatically increasing on-campus sections to accommodate more students, could we redesign more blended models that would enable instructors to teach more students as effectively, or more students without increasing physical space?

Even a 10% saving or increase in effectiveness would be worthwhile for most institutions – even better if this could be in the way of savings for students on tuition fees. In the long run, I do believe that we could reduce unit costs for teaching through online learning, not by huge amounts, but certainly by up to 10 per cent.

However, this requires developing a deliberate strategy, widespread consultation, careful implementation, and above all, deliberate measurement of the results. And for most students this would still mean a significant campus experience.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.