What is north in Canada?

In a country as vast as Canada, ‘north’ is always relative. Sudbury (46º N) is considered to be in Northern Ontario, but by latitude it is south of Vancouver (49% N), although undeniably much colder in the winter. (Cold though is not a good criterion – this February it was cold everywhere in Canada!)

In terms of post-secondary education, there are about 20 Canadian colleges and universities in the range of 52º to 56ºN, which would cover institutions in some fairly large cities and towns, such as Edmonton, Saskatoon, Fort St. John, Fort McMurray, Prince Rupert and Prince George, for instance, as well as several colleges with campuses in fairly small towns. These could all certainly claim to be in the north. But the far north is well beyond even these northerly habitations. In particular, I am interested here in five institutions operating north of 56º, because they face unique challenges in providing post-secondary education.

Far North post-secondary institutions

There are four institutions with campuses in the far north:

- Yukon College, Whitehorse, Yukon (60ºN)

- Collège Nordique Francophone, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories (62ºN)

- Aurora College, with campuses in Inuvik (68ºN), Fort Smith (60ºN) and Yellowknife (62ºN), in the Northwest Territories

- Nunavut Arctic College (70ºN), Nunavut

In addition, I would like to include the University College of the North, which has a mandate to serve Northern Manitoba. Although its two main campuses are in The Pas (54ºN) and Thompson (56ºN), it also has centres in Churchill (59ºN) and several other locations north of 56º.

The unique challenges of post-secondary education in the Far North

All five of these institutions face two common challenges, one geographical/demographic and the other historical.

Geography

The greatest challenge is that these institutions are responsible for providing post-secondary education to very small populations over vast territories and extreme weather conditions.

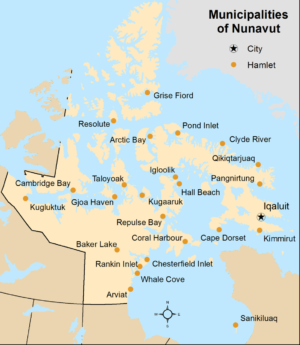

Nunavut Arctic College serves a total population of 33,000 spread across an area of just over 2 million square kilometres. Nunavut Arctic College has about 1,300 students, located in four campuses and 23 community learning centres spread across the whole territory.The Cambridge Bay campus is 1,700 kilometres, and two time zones, from the Iqualuit campus. There are no roads or railway, of course, and flying is usually by charter plane and heavily dependent on weather conditions. Nunavut is a territory funded primarily by the Federal government of Canada, but it does have its own elected legislative assembly.

Aurora College serves a total population of just over 41,000 spread across an area of 1.34 million square kilometres in the Northwest Territories. It has about 800 students taking post-secondary qualifications, with three campuses in Fort Smith, Yellowknife and Inuvik, and 23 learning centres across the province. Again, there are few direct roads between major towns within the territory – for instance it is 4,000 kilometres by road between Yellowknife and Inuvik, or two and a half days of non-stop driving – not recommended, even in summer. (I have driven from Whitehorse in the Yukon to Inuvik, then took a charter flight – in a small Cessna – to Tuktoyaktuk on the Arctic Ocean, but only in the summer. It was though one of the most amazing trips I have ever done). There is now an all-weather road all the way to Tuktoyaktuk from Inuvik. Nevertheless travelling between locations within the territories is still difficult and very expensive. The Northwest Territories is also funded by the federal Government of Canada, but has its own elected legislative assembly.

There is also a francophone college in the Northwest Territories, Collège Nordique Francophone, based in Yellowknife. It is relatively young, being founded in 2011, and has about 150 students.

The Yukon is the smallest and most western of Canada’s three federal territories, with a population of approximately 36,000 spread over an area of 480,000 square kilometres. The majority (25,000) live in Whitehorse, and another 1,500 or so in Dawson City, so the population is more compact than in the other territories. Yukon College has about 800 students taking post-secondary courses. Its main campus is in Whitehorse, with 12 regional campuses across the Yukon.

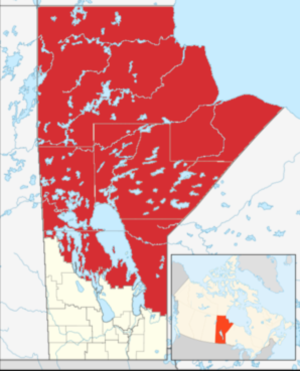

Lastly, the University College of the North (UCN) serves an area more than 20 per cent larger than Germany, but with a total population of just under 90,000 inhabitants, of which more than 60 per cent are Aboriginal. It was once part of the Northwest Territories, but was ceded to Manitoba in 1912. The vast majority of the region is undeveloped wilderness and features long and extremely cold winters and brief, warm summers. The population is scattered across very small communities. The largest city is Thompson, with 13,000 people. In Churchill, polar bears roam the streets at certain times of the year, which seems to me to be a very good reason for studying at home. UCN has a total of just under 1,200 students a year, with main campuses in The Pas and Thompson, and 12 community learning centres spread across northern Manitoba. UCN is funded by the province of Manitoba.

One common feature of the colleges in the three territories is that the colleges offer some university-level courses, mainly at the bachelor’s level, but as yet, there is no full university in any of the territories, although all five are members of the international University of the Arctic, a cooperative network of universities, colleges, research institutes and other organizations concerned with education and research in and about the North.

History

The second major challenge for these institutions is historical. First of all, most of the territories have a majority of aboriginal people who historically have been neglected economically and educationally. The territories until very recently have been administered by the Federal government in Ottawa, which in general does not have a constitutional responsibility for education (elsewhere, this is the responsibility of the provinces). Thus there has not been the same level of expertise or indeed commitment in the past to education in the far North, which for a long time was left either to missionaries or traditional knowledge passed down from generation to generation by the aboriginal peoples.

One unfortunate consequence of this is that there is still a higher proportion of the population in these areas without high school qualifications. Increasing access to under-represented groups is a major challenge. Combined with the low density of population, post-secondary institutions have to manage very few students over huge areas, and cover a very wide range of educational provision, from adult basic education through to graduate level studies. At the same time, and influenced by climate change, the territories in general are expanding economically, particularly in mining, so demand for post-secondary education and graduates is increasing.

Is online learning the solution?

Apparently not, and, as we shall see, for very good (or in fact very bad) reasons.

The two largest/most northerly territories have no online or distance learning, as far as I know. Neither Aurora College nor Nunavut Arctic College offer online courses. Collège Nordique Francophone is very small and has just a handful of students taking at least one online course.

Yukon College (in the most compact of the territories) however has nearly 400 students taking at least one online course (45% of all their students) and 37% of all their course registrations are in online courses, way above the national average.

The University College of the North in Manitoba also has a much higher proportion of students taking at least one online course than the national average (55% compared with the national average of 17%), although a relatively small proportion of all course enrolments are in fully online courses (6%). In other words the UCN students are taking only one or two online courses in their program.

The delivery model for all five institutions is primarily based on distributed face-to-face learning centres. These are locally based.

This does not mean of course that students in the far north can’t get relevant online courses from other institutions further south, provided they have adequate Internet access. For instance Trent University in Southern Ontario offers an online diploma in Circumpolar Studies.

I suggest there are two explanations for these findings.

Poor or non-existent Internet service

The first is that apart from the Yukon, there is very poor Internet service in the far north of Canada. For instance UCN’s Churchill campus has only 2 MBS per second connection at the moment – that is equivalent to the old dial-up modems of the past. In the far north, the only Internet connection for most communities is via satellite, which is very expensive, especially if a return uplink is used, as is really necessary for online learning.

This is less of a challenge in the Yukon, where most students live in either Whitehorse or Dawson City, and where there are better internet services. However, even for UCN students their best or most economical chance of Internet access will be at a local centre or one of the main campuses.

There are plans from the Federal government to increase Internet access in the far north. Almost $50 million has been committed, with service from a dedicated circumpolar satellite, and Iqualuit may see a seabed fibre optic connection in the distant future. However, to date, these plans still have to be implemented, and in any case in many of the more remote communities in the far north Internet speed and capacity still will not be cheap enough for the consistency and quality of service needed for effective online learning.

Cultural

I am guessing here but I have noticed in our survey of post-secondary institutions in Canada that aboriginal communities are less inclined in general to learn online. The importance of learning within their own cultures with their own people is particularly important for many indigenous people.

I am not saying that indigenous people cannot learn online, but for online learning to be more generally accepted, it needs to be designed to respect and build on aboriginal ways of learning. In fact, that might also benefit non-indigenous learners as well.

Important lessons

Online and distance learning is not primarily driven by distance, but by flexibility and low cost technology access. Thus online learning is more likely to thrive in more densely populated areas where there is access to quality Internet services. In very remote regions, online learning will usually need to be supplemented or incorporated with local learning centres and local communities.

Also we should not underestimate the importance of low cost, high quality and easily accessible technology for online learning to succeed.

Nevertheless, economic and social development in the far north of Canada requires better quality education made accessible to everyone, building on the regional centres. However a major investment in Internet technology is still necessary in these areas because not everything can be delivered through local campuses, especially for the growing number of workers who need access to cultural and learning opportunities. For effective online learning that enables for full video interaction from the remotest communities, even greater levels of investment than those currently planned will be needed.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Surely online learning, like other forms of mediated learning, requires students to have a reasonably strong capacity to manage their own learning, which disadvantaged students are unlikely to have.