The need to reduce costs

In three previous posts, I tried to make the case that public universities and colleges were losing the support and particularly the trust of government and voters. The public post-secondary system has expanded enormously, but the cost of a degree or qualification has gone up faster than inflation, placing increased economic pressure on both governments (through taxes) and individuals (through tuition fees). I will argue that to win back the support of public and government, institutions must look to ways to reduce costs, while maintaining access and quality.

I recognise that what I am proposing will be very controversial and is ambitious. In the end, it will be up to the institutions mainly, but also with the support of government, to find a solution to ever increasing costs. I will be suggesting a radical approach, in the hope that this will spur discussion and engagement.

Set a target

I suggest that either government or the institutions set a challenging but realistic target for reducing the costs of a qualification. I would propose that the ‘true’ cost of a qualification (degree, diploma) should be reduced by 30% over a three year period, plus one year to develop an institutional plan or strategy for achieving such a reduction. Thus the target would be a 30% reduction from present costs by the end of 2029 (or 10 per cent per annum). In this and later posts I will make some suggestions on how this can be done.

Conditions

There would be conditions on this:

- the cost reductions need to be accommodated within existing collective agreements for salaries, although some conditions of service (e.g. research time for certain categories of instructor) would be negotiable

- overall access/enrolments need to be maintained across the system (although may be reduced in some institutions and increased in others)

- graduation rates and standards are to be at least maintained and possibly improved

- cost reductions will be primarily the responsibility of the institutions themselves, but supported by government

I will discuss these issues in more detail in later posts but the aim is a substantial cost-reduction without a loss of ‘output’ or benefits. You will see that I believe there are viable ways to do this.

Use activity-based costing

Note that I said the ‘true’ cost of a qualification. This would cover the costs of instructors, and the essential overheads needed to deliver the program. It would include an annualised cost for the use of laboratories, for instance, if laboratories are used. The ‘true’ cost would need to be covered by the actual tuition fee plus any government support or subsidy (at the moment through a general grant to the institution). Costs of a program would include the time spent by instructors in delivering content, and supporting and assessing students, and an allowance for general overheads (such as heating and lighting classrooms, IT services, etc.). In some institutions, general overheads are often charged at a rate as high as 40% on top of the direct costs of teaching and assessment.

In some cases, the true cost for some qualifications may be less than the tuition fee, because of economies of scale. There is often extensive cross-subsidisation across programs. In other words there is not usually a direct relationship between actual costs and the tuition fees charged. However, tuition fees are just part of the revenues used to cover costs.

To assess the ‘true’ cost of a program, you need activity based costing. This relates both direct and indirect costs of a program to revenues. The aim is to ensure costs of a specific program are fully covered by revenues generated by that program.

In most public post-secondary institutions, activity-based costing is either not used at all, or for a minority of programs such as professional masters, where tuition fees are expected to cover all costs. The more traditional system is ‘historical’ allocation of funds to academic departments, based on what was received the previous year, plus or minus a percentage dependent on the general revenues anticipated for the coming year. In really bad years financially, some programs deemed to be too expensive or not cost-effective (i.e. low student numbers) may be closed, but this is usually a last resort in historical allocation.

One crucial difference between activity-based costing and historical allocation is that in activity-based costing, the revenues (tuition fees plus any subsidy, usually from the general government grant) go directly to the program, not, as with historical allocation, to general funds (the Provost’s Office) then to the academic department, and with activity-based funding, general overheads are paid directly to the relevant administrative areas. It is still possible to cross-subsidise with activity-based funding by adding an extra ‘tax’ on the program (in other words it has to make a profit, and that profit is clawed back by central administration/the Dean’s and/or the Provost’s Office).

Because general overheads can cost up to 40% of a program’s revenues, with activity-based costing there is added pressure on the departments charging overheads to become more efficient. Also, as programs move to more online delivery, the overhead mix can change quite dramatically (no need to pay for classroom overheads, for instance, but IT costs go up).

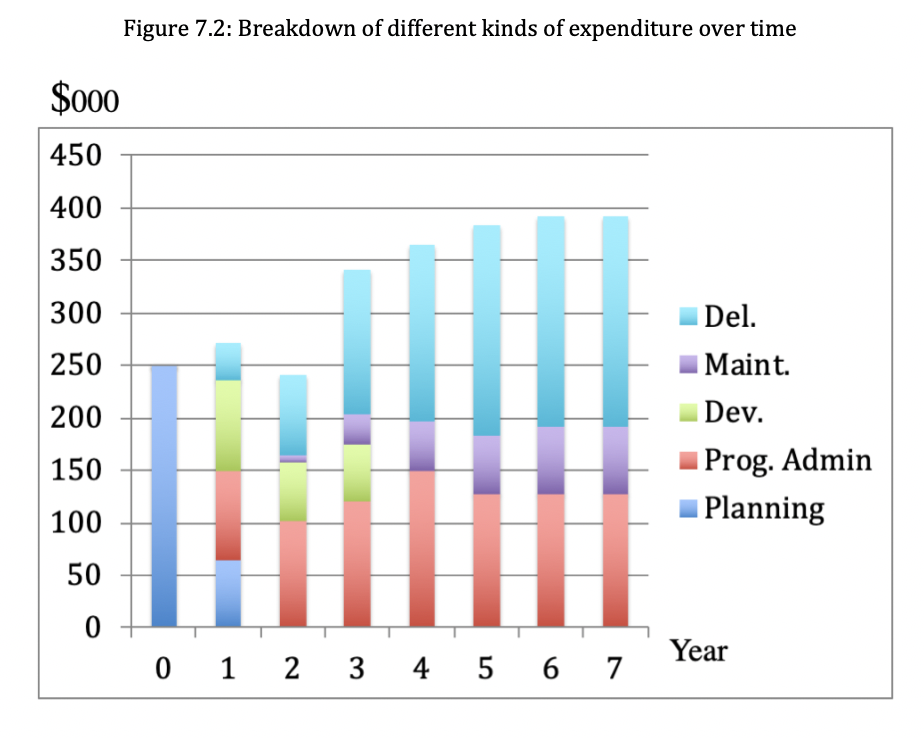

The main cost of a program is the instruction. In activity-based costing, one method to assess the cost of teaching is based on the time instructors spend on the course, including student support and assessment. I used activity-based accounting when developing a fully online professional masters at UBC. Using only tenured faculty, for the equivalent of a three credit course, we estimated 12.5 days for course development, 12.5 days for course delivery, and 4 days for course maintenance (Bates and Sangra, 2011). We also made similar estimates for the instructional designers and multimedia designers who worked on the courses.

There are various assumptions that can be made (and challenged) about how to do activity-based costing, but I am arguing that to get a grip on the actual cost of a specific program, activity-based costing is essential. Once you have a breakdown of the actual costs of delivering a program, you can then look at ways to reduce costs overall.

Next up

In my next blog post (due within a day or two from now) and later posts I will be making some specific suggestions about how the costs of a program can be reduced by 30 per cent over a three year period without undermining quality or reducing enrolments. These suggestions will include:

- course re-design, using advanced learning design and learning technologies (including AI), aimed at cost-reduction while maintaining quality

- increasing teaching load and slimming research activities in selected ways

- greater inter-institutional collaboration including sharing of programs across institutions

- improved training in modern teaching methods for all instructors

- incentives

Reference

Bates, A, and Sangra, A. (2011) Managing Technology in Higher Education San Francisco: Jossey Bass

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Thanx for this.

I suggest that it is important to distinguish between 2 techniques.

Activity based costing ‘is a costing method that identifies activities in an organization and assigns the cost of each activity to all products and services according to the actual consumption by each’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Activity-based_costing).

Responsibility centre management is a budgeting technique that makes revenue-generating units wholly responsible for managing their own revenues and expenditures (https://drexel.edu/provost/priorities/rcm).

It is possible and I expect common to have one without the other.