I am writing an autobiography, mainly for my family, but it does cover some key moments in the development of open and online learning. I thought I would share these as there seems to be a growing interest in the history of educational technology.

Note that these posts are NOT meant to be deeply researched historical accounts, but how I saw and encountered developments in my personal life. If you were around at the time of these developments and would like to offer comments or a different view, please use the comment box at the end of each post. (There is already a conversation track on my LinkedIn site and on X). A full list of the posts to date will be found toward the end of this post.

The end of the road at UBC

I have been putting off writing this post now for over three months, because it was one of the most painful periods in my professional life. Also, after all these years I am still not sure what really happened, so this is my personal view. Others, such as Mark Bullen, probably have a better picture. If so please comment at the bottom of this post.

Distance Education and Technology at UBC in 2003

There were approximately 5,000 students in online distance credit programs (part of regular degrees) in 2002-2003 taking courses through DE&T, most taking one or two online courses at a time (it was still impossible to do a full UBC undergraduate degree at a distance), plus three fully online masters programs either already launched or in production.

By 2003, distance enrolments through DE&T had grown at a steady 12 per cent per annum over the previous seven years.

The revenues for DET in 2003 were roughly $5 million, of which

- 60% were student tuition fees to cover tutoring and distance student services,

- about 20% in direct grant from UBC’s general operating funds that mainly covered course development costs

- 4% in research grants

- 2% for the Director’s office (from Continuing Studies)

- 14% for university overheads

Almost all the distance education courses had been moved online, and fully online, cost-recoverable masters programs had been launched in educational technology, creative writing and rehabilitation sciences.

The Distance Education and Technology Department had also set up a research group, MAPLE (Managing and Planning Learning Environments), which had brought in over $1 million in research grants over three years.

I had also been the chair of a university-wide committee, Advancing the Creative Use of Learning Technology (ACCULT), which put forward a number of recommendations to strengthen the use of learning technologies throughout UBC, and I worked with UBC Media Services to develop a video on how teaching with technology at UBC might look in five years time (i.e. 2005). The report and video went to UBC’s Senate and were approved.

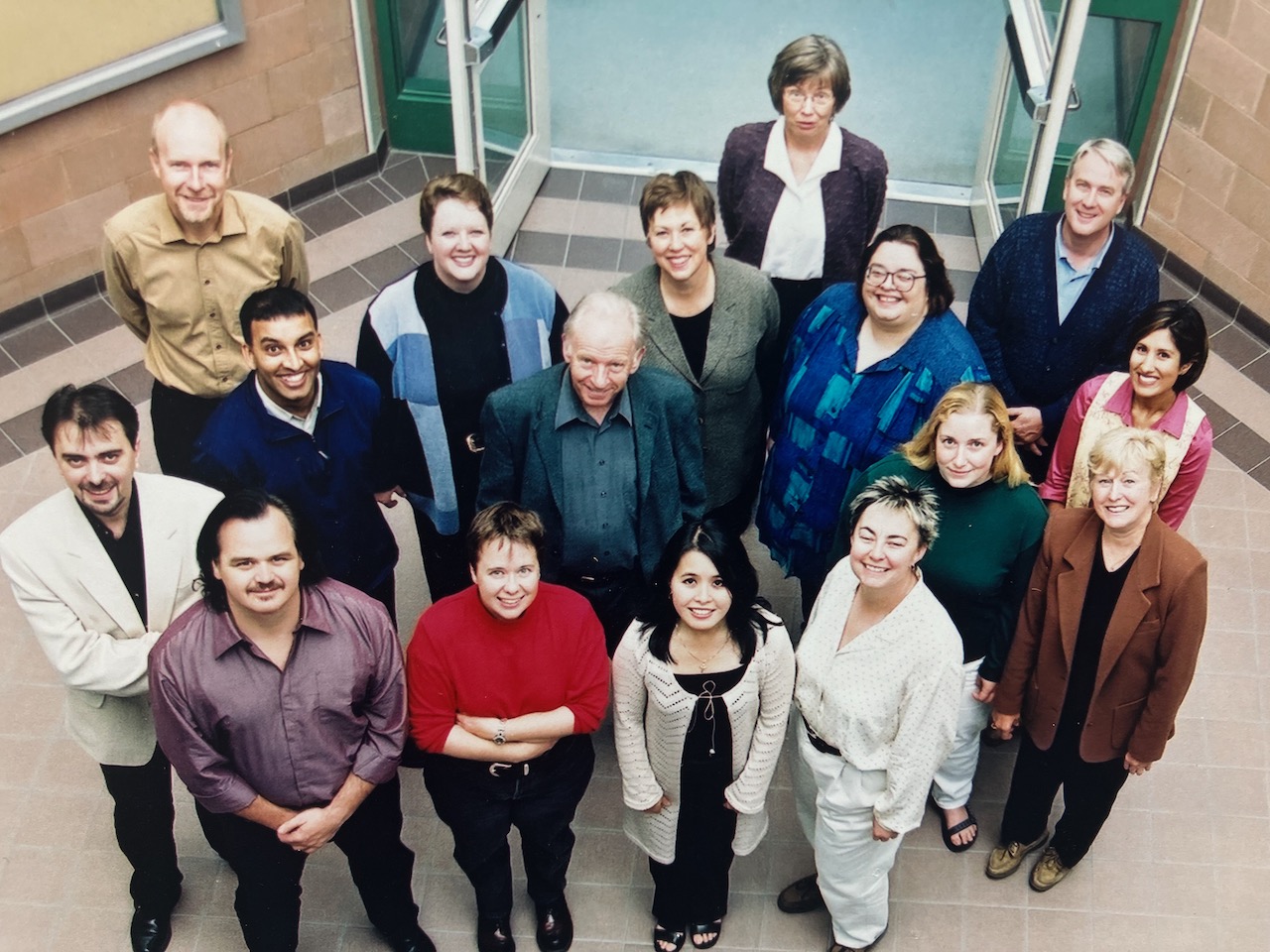

Above all, DE&T had a tremendous team of professionals (instructional designers, web designers, students service managers) dedicated to the design, development and delivery of high quality online distance courses and programs.

From feedback received through conference invitations, UBC was recognised both nationally and internationally for its innovation and quality in online learning and distance education.

What could possibly go wrong?

Chaos and confusion

Well, in 2003, UBC’s senior administration (the Committee of Deans) decided that Distance Education and Technology as a unit was to be largely dismantled, all distance education courses for credit were to be returned to and run by the relevant faculties, and my services were deemed no longer needed. This followed an external review of Distance Education and Technology, whose recommendations were largely ignored by a subsequent sub-committee of Deans, who recommended the dismantling of the unit.

This resulted in almost three years of chaos for distance education students as Faculties tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to take responsibility for their distance education courses. In the end, the decision was reversed, and the remaining staff in Distance Education and Technology were moved to the Centre for Teaching and Academic Growth (TAG).

Forced into retirement

I should have realised something was up when in a meeting with Jane Hutton, Neil Guppy and someone from HR in late 2002, it was pointed out that I would be due for retirement in 2004, as UBC had mandatory retirement at age 65 (this would later be abolished in 2009), and they wanted to know what my plans were. It was made clear that my contract with Continuing Studies would not be renewed after 2003. I wasn’t happy about this. Although I had had a scare about cancer in 2001, the operation was completely successful, and by 2003 I was well and fit again. However, it looked like I didn’t have a choice because of the mandatory retirement policy. I was in the administrative staff category, I did not have tenure, and was absolutely dependent on the funding of my position from Continuing Studies.

I was increasingly doing consultancy contracts with other universities and organisations, but the fees went to into the DE&T accounts. At the meeting, I asked if I decided to retire at the end of 2003, would there be objections to my taking the consultancy contracts with me. I was told that this would be fine, so I agreed early in 2003 to resign on 1st January, 2004. As I had a considerable amount of sabbatical leave owing, I would step down as Director of DE&T in July 2003, and Mark Bullen would be appointed acting director.

University politics

I was never sure exactly what went on behind the scenes, or at least all the reasons behind the decision to dismantle DE&T, but primarily it was about money (unofficially), and secondly about the future vision for learning technologies at UBC going forward (officially).

In terms of money, the Deans saw all the undergraduate tuition revenue from ‘their’ courses going to Continuing Studies (where Distance Education and Technology was located), and about $1 million of general operating revenues going as an annual grant to DE&T. What the Deans didn’t really understand was that it was money in and money out; in other words all the tuition revenues received were paid out to hire tutors, and most of the grant money was paid to faculty and instructional designers for course development and the rest to supporting distance students. There was no balance going as profit to Continuing Studies, and even my salary was paid by Continuing Studies, not from DE&T’s revenues nor from the university’s general operating grant.

In terms of future strategies, after the ACCULT report had been approved by Senate, there was considerable discussion across the university, and particularly amongst the Deans, about the best way to organise and support the development of learning technologies. As well as DE&T, a number of different teaching support units at UBC, such as the Centre for Teaching and Academic Growth (TAG), the Office of Learning Technologies (OLT), Telestudios, and IT Services, had sprung up or expanded, with some reporting to the VP Academic/Provost and others to the VP Administration. At the same time, some of the Faculties had hired their own instructional design or educational technology support staff, and a couple ran their own distance education programs. Generally, the Deans were unhappy about these central units, as they took money from the general operating fund which they felt should be going to their Faculties, and that teaching was best managed within the Faculty.

A review of DE&T had been mutually agreed with the VP Academic’s Office as necessary back in 2001, mainly as a result of the ACCULT recommendations. My own view and that of my colleagues in DE&T was that:

- distance education required an integrated system for the design, development and delivery of online programs, and therefore DE&T should remain a single, integrated unit;

- however, a strong, professional Centre for Educational Technology should be established and DE&T, which was focused on credit and online programming, should be part of a new Centre.

The majority of Deans, on the other hand, wanted a decentralised system, with ed tech and DE support within each faculty.

DE&T objected from the beginning at the decision to review DE&T in isolation. To move the proposals in ACCULT forward, DE&T argued that the roles and relationships of all the different central teaching support units at UBC should be reviewed together, including DE&T. This suggestion though was ignored by the senior administration.

A high quality external review panel, including Terry Anderson from Athabasca University and Joel Hartmann from the University of Central Florida, received input from DE&T, including a vision and strategic plan.

On receiving the external panel’s report, Barry McBride, the Provost, reported:

The Review team had tremendous praise for the unit, for the staff expertise and commitment, and for the leadership of Dr. Tony Bates. They commented, for example, on the “high level of expertise” contained within this “internationally recognized unit.” There can be no doubt that under Tony’s leadership the unit has been very successful…. Over the next months we will be looking for new organizational alignments and an effective financial model that links the strengths of DE&T more closely with the Faculties and e-learning support units that many have developed. DE&T will now report to Neil Guppy, Associate Vice President, Academic Programs.(1)

Following this, Neil Guppy set up a very small Committee of Deans, with himself as chair, two Deans (Arts and Technology), and Mark Bullen (I was on sabbatical leave). However, despite Mark’s strong objections, the two deans on this committee basically planned to eviscerate the design, development and delivery functions of DE&T by:

- moving all course development and delivery funds to the faculties,

- moving all research activities to the Faculty of Education,

- with DE&T left solely with marketing and central information sharing. (2)

This proposal was agreed by the Council of Deans at the end of December, 2003.

This resulted in over a year of chaos in terms of distance education. The Faculties quickly realised that there was no ‘spare’ money and they would need to either hire new staff or existing staff from DE&T. Some of the smaller Faculties simply did not have the resources after re-allocation from DE&T to manage distance education as well as on-campus teaching. DE&T had benefited from the economies of scale of a central unit. Several key DE&T staff left UBC for more secure jobs during this attempted transition. I had retired by this stage and Mark Bullen was left with the terrible job of trying to keep services going when few in the Faculties knew what they were doing.

As a result, in March, 2005, nearly three years after the decision to review DE&T, a new AVP, Academic Programs announced the decision has been made not to proceed with the dissolution of DET (3). Remaining DE&T staff were moved to the Office of Learning Technologies, which later merged with TAG to become the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology, thus ensuring the integration of online learning with other digital technologies at UBC.

To some extent UBC now uses the ‘mixed’ model that Bruce King developed at the University of South Australia, with some learning technology staff assigned long-term or permanently to a Faculty, but with strong liaison with the central unit as needed. This was the model that DE&T originally proposed to the External Review committee. This model seems to have been working well since 2005.

Why did the Dean’s strategy go so wrong?

A number of factors resulted in the attempted dismantling of DE&T.

There was a clear anomaly in that almost all the work of DE&T was focused on students taking regular degrees for credit, but the unit was located in Continuing Studies, whose focus was on non-credit programs.

Walter Uegama, the AVP Continuing Studies, and a strong supporter of DE&T, had to step down in 2000 for health reasons and was replaced by Jane Hutton. She had supported a number of separate initiatives to establish online non-credit programs in Continuing Studies, and probably believed that the $1 million that went to my salary might be better spent on non-credit online learning, although she never said as much to me.

Also, in 1998, Barry McBride replaced Dan Birch as Provost and VP Academic. Dan had been a strong supporter. In 1999, McBride appointed Neil Guppy, a sociologist, as AVP, Academic Programs, with responsibility mainly for the teaching at UBC, and was the main liaison with me in the Provost’s Office.

Another factor perhaps was that during 2003 I wasn’t at UBC for long periods. I had accumulated sabbatical leave and was away a lot of the time working it off before I retired at the end of the year. However, I doubt I could have done a better job than Mark Bullen, who had to face two very intransigent and self-serving deans with little support from outside DE&T.

I moved on in 2004 to a highly successful 20 year career as a private consultant (more on that to come).

Lessons learned

- I never regretted my time at UBC; it was probably the most intense, constructive and satisfying part of my career.

- Some deans are like robber barons in the court of King John; they pursue their Faculty’s interests above that of the university as a whole.

- It is much easier to destroy than to build.

- 85 is the new 65, as far is retirement is concerned (if you are fortunate enough to have good health and a passion for your work).

- Everyone needs mentors and champions with power and influence. I lost mine and made the mistake of not quickly finding new ones at UBC.

- As the late soccer manager Tommy Docherty said: ‘When one door closes, there’s always another to slam shut in your face.’

- There is nothing more satisfying as a manager than to have a dedicated, innovative, professional team working for you, but you will be incredibly fortunate if you have one.

- There are few employers more devious than a university.

Lastly, thanks to all the wonderful staff who worked in DE&T, and to all the innovative faculty at UBC I had the fortune to work with. I still miss you all, 20 years later.

Make a comment

If you were around at this time, and have anything to add, please use the comment box at the end of this post.

References

- McBride, B. (2003) Distance Education and Technology (DE&T), Internal memorandum to Administrative Heads of Unit, July 17

- Isaacson, M. (2003) Re: DE&T Committee Internal memorandum to N.Guppy, December 15

- Kindler, A. (2005) DET dissolution cancelled Internal memorandum to M.Bullen, Director of DE&T

Next up

Working at the Open University of Catalonia

Previous posts in this series

Here is a list of the posts to date in this series:

A personal history: 1. The start of the Open University

A personal history: 2. Researching the BBC/Open University broadcasts

A personal history: 3. What I learned from Open University summer schools

A personal history: 5. India and educational satellite TV

A personal history: 6. Satellite TV in Europe and lessons from the 1980s

A personal history: 7. Distance education in Canada in 1982

A personal history: 8. The start of the digital revolution

A personal history: 9. The Northern Ireland Troubles and bun hurling at Lakehead University

A personal history: 10. Why I emigrated to Canada

A personal history: 11. The creation of the OLA

A personal history: 12. My first two years at the Open Learning Agency

A personal history: 13. OLA and international distance education, 1990-1993

A personal history: 14. Strategic planning, nuclear weapons and the OLA

A personal history: 15. How technology changed distance education in the mid 1990s

A personal history: 16. NAFTA, video-conferencing and getting lost in Texas

A personal history: 17. Innovation in distance education at UBC

A personal history: 18. Developing the first online programs at UBC – and in Mexico

A personal history: 19. Some reflections on research into the costs and benefits of online learning

A personal history: 20. Identifying best practices for ed tech faculty development

A personal history: 21. Open and distance learning in Japan and South Korea

A personal history: 23. Open and distance learning in Australia and New Zealand – and 9/11

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Hi Tony. Reading your retrospective gives me acid reflux because it is not dissimilar to the “behind the curtain” changes that had me ousted out of UBC in 2011. This constant tug of war about (1) the role of Continuing Studies and tech-enabled learning (at many post-secs) that continues to this day, and (2) the rubberband widening and shrinking of technology-enabled learning and teaching within each faculty complemented with the continuous existential question of “will the centre hold?” seems to change every 5 years. The governance is like the federal-provincial fights of responsibility, accountability and budgets. Heh I first met you when we were all working/doing applied research via the SFU-led national TeleLearning Network Center of Excellence. UBC and Dr.Tony Bates were held in high esteem nationally in that period 1995-2000. But we’ve all learned that innovation, building high quality teams of instructional designers and technicians, and applying an evidence-based approach to the pedagogies of tech-enabled T&L is no pathway to job security. It seems to threaten some academics-in-leadership roles and it’s the pattern of higher Ed – send it to the provinces (faculties) and then oops this is costly and inefficient, bring it back to the centre.

It’s no wonder you emerged with an international consulting biz and I went looking for even more complex challenges in climate-change capacity-building. We were made for change-making Tony. Now what to do about acid reflux when reflecting on career burn? TUMS or a glass of red wine?

Red wine – definitely

This is a great read, Tony! I have nothing to add to your historical narrative as at the time my focus was mostly on UK developments after the demise of TL-NCE in 2002 (where I was one of the international evaluators, not that I recall any direly negative report of the type that was said to have finished it off) and my involvement in the setting up of the UK e-University in 2000-2003. Not that that went well.

But I hope all your readers get the point that this is not an event frozen in time and thus irrelevant to the current generation of digital learning managers so full of enthusiasm but so lacking in background knowledge (and market/competitor research) but has continued to happen and is happening to this day in universities in several OECD countries. Deans will be Deans and campus presidents remain suspicious of non-campus operations.

I hope and suspect you will have more to say about somewhat later events in the complicated ongoing history of digital learning in British Columbia, where I might have a few tales to tell.

Thanks, Paul. Yes, I will be continuing unless I get arrested for libel!

What a nightmare! I was in Europe, at the UKOU and UNESCO, in those years and only dimly aware of this UBC horror story.

However, it is analogous at many points to the history of Université TÉLUQ in Quebec. According to Michel Umbriaco, who was at TÉLUQ from its foundation in 1972 until well into this century, there were 8 attempts by the other units of the UQ over the years to close TÉLUQ down. The arguments, as at UBC, were that ODL should be done by the local institutions, despite their complete lack of expertise. They disliked having competition from a ‘national’ body that knew what it was doing.

It’s really a wonder that TÉLUQ survived – and a credit to the inherent power and importance of ODL

Thanks, John. Yes Téluq is a remarkable success story due to some very skilled and determined managers and staff

Hi Tony,

I first experienced your insight inti distance learning when I as a young man at the University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Humanities, listened to your keynote about how to scale elearning or distance learning from “the lone ranger” attitude. This was in 2003 or 2004 I believe.

Some years later I was promoted to manage the newly formed Academic Support Centre consisting of printing services, audiovisual productions, elearning and academic writing. The coming years (2005-2016) I learned first hand the 8 lessons you have stated above.

The Academic Support Centre was reorganised and changed name to ITMEDIA. Printing Services was put under Facility and the Academic writing centre (two employed there) was managed by HR. My new department now consisted of elearning and audiovisual production. However we collaborated with the Danish Broadcasting Company (Denmarks Radio) having student producing radio episodes for some of the various channels, making audiowalks, podcasts etc for museums and art galleries (this was in 2007-2010), was approved by Apple to iTunesU… But for some reason things were going slow. From 2006-2008 the university was planning the second phase of constructing the new Souther Campus and my department was heavily engaged in the programming. The new campus ended up having 887 kms of fiber cabling enabling our department to manage live video streaming between auditoriums, teaching rooms, having guest professors perticipate in lectures from abroad or the other way around like also conferences were held with online key-notes. Something quite normal today – except this started in 2007!

Well, lots of things went well and we were a small but dedicated department that also managed to turn one four day conference and three one day seminars from onpremise to online in a very short time back in 2010 when the volcano under Eyafjallajökul in Iceland stopped flight traffic over large parts of the world.

Well, despite all the succes the dean in 2016 gutted the department and laid off half of the staff. Research dissemination through audiovisual media and elarning was not important.

Now in 2024 the Tv-studio is up and running again with one of my former employees running it and the remain 566 square metres will most probably reopen, but this time as part of facilitating the entire university.

I can look forward to another 14 years until retirement. I now work at a university college in the IT-department with implementing IT-systems and platforms. Not exactly interesting but puts butter on the bread. Instead I have learning to forge and have been doing that for 12 years now. I enherited a lot of tools from my late father, and I now plan to a carreer change in due time when I have the infrastructure i.e blacksmith shop ready.

Thanks for the inspiration and insight I got from your keynote back in the days. I wish you all the best!

God dag, Uwe, og tusen takk! Yes, I remember well my visit to the University of Copenhagen in 2005- I think my talk was called ‘Why universities must change.’ I am sorry you had to go through a similar experience to me, but I wish you every success in your new career as a blacksmith/metal worker

Thanks Tony.

I think you speak for many, certainly for me. As Trent Batson says, “if you’re not fired At least once (in positions In educational technology), you’re not doing your job.”

Steve Ehrmann writes in his excellent book about the rare institutions that effectively maintain quality, cut costs, and retain/increase enrollments. (“Quality, Access and Affordability “) They have one thing in common – – a stable core group of enlightened leaders. Unfortunately, stable leadership is extremely rare.

Many thanks, Gary. Yes, I very much agree with all that Steve Ehrmann writes

Hi Tony

A very interesting account of your dismissal from UBC. It made a huge loss, the rest of use huge gain:-),

I had a similar experience in 2006 (must be something in the air for that period of time) Suffice to say that when dealing with the ‘Robber barons’ of academia and there administrative mates, you need to remember in their eyes, you are just a number on the staff list (lessons learned) Interesting to note that their are several(many?) others who have gone through the same experienceI.

I agree with you that 85 is the new 65! Long may it last.

Cheers

Richard

Thanks, Richard – but you have lots of time to get to 85!

Hi Tony,

Your article brought back many good memories of working at DE&T. I was lucky to be part of the DE&T team and without a doubt it was the highlight of my UBC career. I’m thankful to have had the opportunity to work under your guidance and leadership and later when UBC started to dismantle DE&T, I was grateful for the leadership of Mark Bullen and later Doug Cronk who had to continue to navigate through this sad chapter. It was a huge loss for UBC when considering what could have and should have been.

Chris

Many thanks, Chris – much appreciated

Tony, so many of your insights resonate with me. I spent the first 25 years of my career in CE units but that had responsibility for expanding and building ODL. The first thing I thought of was what a former higher education leader named Clark Kerr who created the higher education master plan in California. He was rather outspoken and was asked by a journalist: Why are the politics and in-fighting in universities so vicious? Mr. Kerr’s response: ‘Because the stakes are so small.’ Indeed, as we know that answer is a blend of fiction and nonfiction. Sometimes the stakes for our stakeholders are important. Ironically, Clark Kerr was fired by an up and coming Governor in the 1960s named Ronald Reagan.

I faced similar battles in the years you describe and the tensions over program revenues in CE units that were successful were always about money distribution. Education in the U.S., like Canada, is under the oversight of the states/provinces and this usually meant CE was cost-recovery – no hard budget moneys only student tuition/fees. CE/DE had to create the revenue to run the unit. I have often been asked what it was like to run a unit like this around the millennium when ODL was expanding in traditional institutions. I often said it was like going to work every Monday morning knowing you going to get mugged (figuratively) before 9:00 a.m. A dean calls and wants more revenues, faculty complaining the departments were not giving them credit for P&T, the president wants an MBA online in China. It never stopped. I often laugh when I hear people say Deans don’t care about ODL . . . I worked on a major university campus from 1998 – 2002 in which 6 LMS were operating – each by a college that wanted to be the ODL leader. In the end all of this mattered little because the moral of the story never changed for CE/DE units – do your job too well and make money and the Deans send their raiding parties – do your job poorly and sooner or later come the cries to shut down the CE/DE unit for streamline it in to oblivion.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of all of this is it seems inevitable that when these kinds of bureaucratic, petty politics take over the person in the top leadership position knows absolutely nothing about CE or DE. At the end of the day, one seldom wins these battles because like Mark Twain reminded us ‘Of course truth is stranger than fiction . . . fiction has to make sense.’ And we all know sometimes, not all the time, looking for common sense in the academy is futile. One has to laugh that a social organization whose sole survival is based on the create and use of data often dabbles in petty politics for personal gain positioning. I finally met a senior VP/Provost that I would not back down from and I went to battle – I knew he would win but I decided to fight until be both had no choice but to leave the institution. I resigned before he could fire me and two days later the President told him bye bye. He had dismantled the CE unit so badly there was nothing left and it was phased out and the Colleges took over their respective outreach programmes and central tech unit now manages digital. So while many of my colleagues over the years have said everyone ought to get fired at least once in their careers if they are worth their weight in salt, I also believe one has to stand and fight and take the consequences and fight for right. Ironically, as you noted, that was 2007 and I have had the most successful and rewarding 18 years of my career. As noted above, HE has many many excellent managers in our universities. We have far fewer leaders that can lead us in to the future. The real leadership issue is 2025 is that most of those in power really don’t know what to do so they hold on to the past which in and of itself only sabotages the future. ‘Managers do things right – leaders do the right things’ (Bennis & Nanus, 1985). Finally, just a kudos you are doing just fine in your new normal for retirement. Rock on!

Many thanks, Don. It’s good to know that one is not alone in this field! Overall, at UBC things worked out in the end, but the main losses were some excellent and highly valuable staff who left for other institutions, and the break-up of a really brilliant team of distance educators whose joint contributions as a team exceeded even their individual contributions.