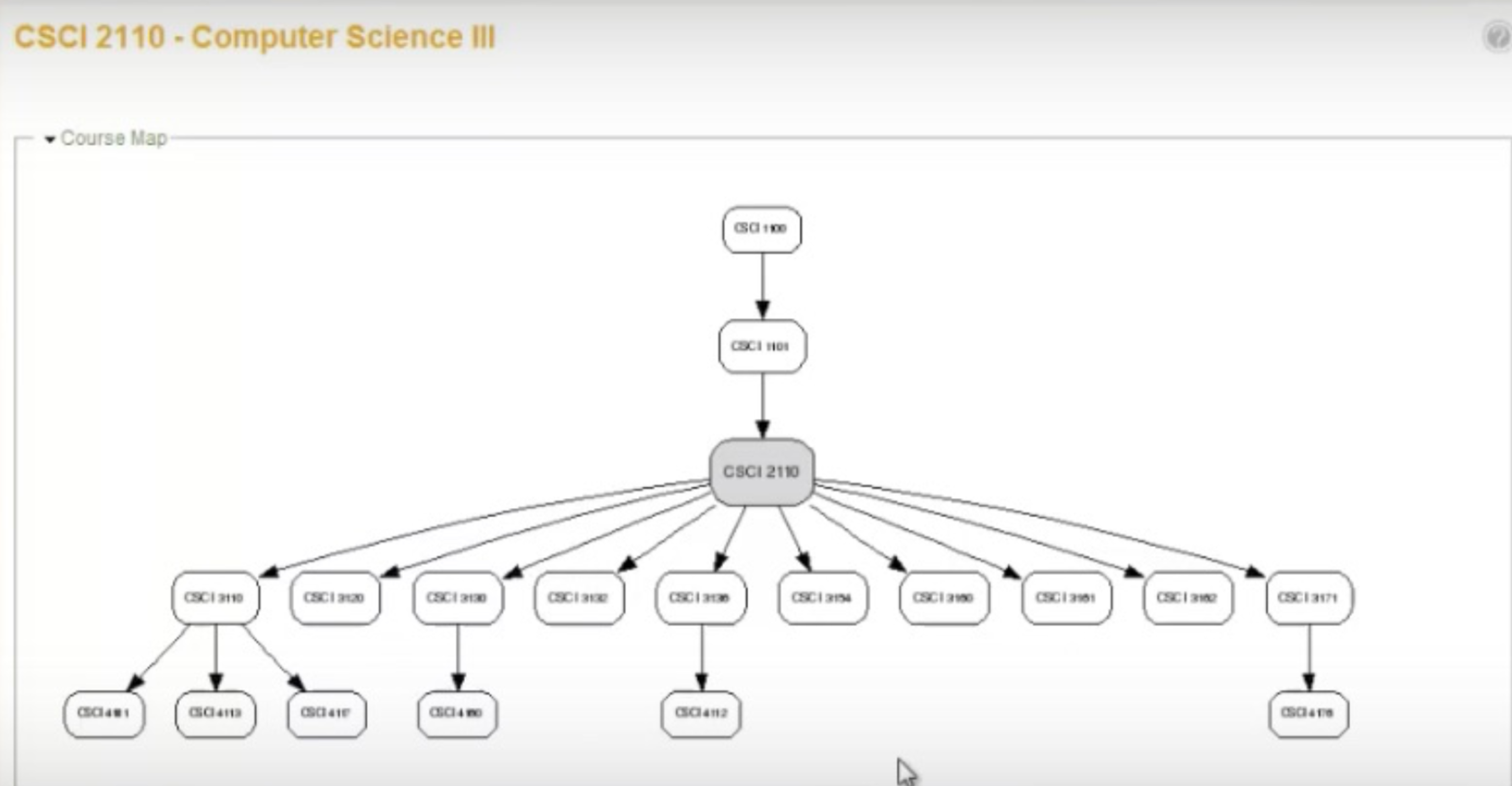

Dalhousie University’s Faculty of Computer Science uses Daedalus software to track students’ learning objectives across and between courses,enabling the measurement of the progression of skills development throughout a whole program.

The challenge

University and college instructors are facing three existential challenges at the moment:

- the demand to teach ‘future skills’ as well as provide subject expertise (see Ehlers and Eigbrecht, 2024)

- learning how best to accommodate/react to the impact of artificial intelligence (and other emerging technologies) on teaching and assessment (see: What should universities and colleges do about AI for teaching and learning?

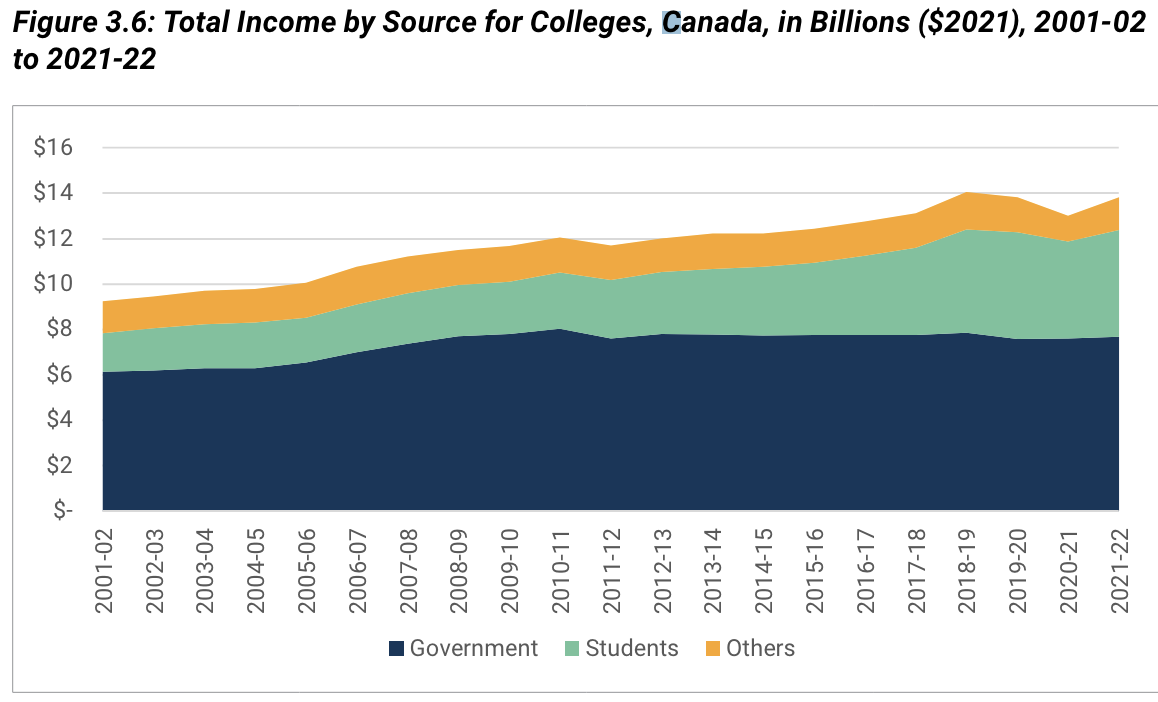

- the eroding financial base of institutions due to stagnant or reduced government funding (see Usher and Balfour, 2023, pp. 40), and, in Canada, the recent cap on international students, whose tuition fees have been subsidising Canadian students; this in turn is likely to lead to larger class sizes in the not so long run

Bear in mind that most higher education instructors are primarily subject matter specialists. They are either trained as researchers or are advanced knowledge experts in their field (through Ph.D. programs); or are qualified craftsmen, again with high levels of knowledge of their particular vocation, such as plumbing or marketing. However, neither group of instructors is required to have anything but the must rudimentary training in teaching methods or educational technology. So ironically, the very people we are looking to develop future ‘soft skills’ in our students lack the the necessary ‘soft skills’ themselves.

Potential impact

We need some data here, but I have have on three different occasions had discussions with university and college staff about these challenges, and three times (usually over a drink following conference presentations), a least a couple of senior instructors, especially in the age range 50-65, have more or less said to me, ‘F••k this. This is not what I signed up for. I’m outa here.’ In other words, they are thinking of either early retirement, a return to their original professions, or a retreat from teaching into research.

However, I would argue that these senior instructors are the ones we can least afford to leave the profession prematurely. These are the ones we need to lead the necessary changes, partly because they carry more influence in their departments than the younger staff, but also because their experience and expertise are hard to replace. If they start leaving en masse, then at least the HE teaching system will collapse from within.

What needs to be done

There are no simple solutions to the increasing challenges being faced by professors and instructors. They need to be tackled at three levels.

- The micro level requires providing more help and support for individual instructors themselves.

- The meso level requires changes at the departmental or institutional level, particularly leadership in ‘selling’ the need to meet these challenges: setting priorities; explaining why the necessary changes are important, providing incentives for change; building partnerships with governments, business and professional accreditation bodies

- the macro level requires governments and the business community to recognise this as an economic productivity issue and provide the necessary resources at a level sufficient to create change.

Micro level changes: supporting individual instructors

I have written on several occasions (see for instance Digital Learning and Faculty Development: a review of Canadian practice) about the inadequate way in which we prepare our instructors for teaching in a digital age. For those intending to work in a university or college, we need to include an introduction within their graduate education to different teaching methods appropriate for teaching skills. We need more online, on demand programs such as UBC’s online Master in Educational Technology and other online, easily accessible programs that focus on teaching methods focused on skills development as well as content acquisition, and on appropriate media selection and use. And above all we need to scale up the number of instructors taking professional development courses at least once a year from around 15% to nearer 100%. Researchers are already looking at ways to use AI to assist with course design as a way of scaling up support for instructors. Teaching excellence needs to be reflected in appointments and tenure in reality and not superficially. This will also mean changing faculty development methods themselves, with more opportunities for on demand, as needed online resources and in-person support. As I wrote earlier the main issue is not so much not knowing what faculty development activities are needed, but ensuring that all those who need it are systematically covered. Too much is left to the personal inclinations of individual instructors. Ensuring systematic faculty development for digital learning will require some significant cultural changes in our HE institutions.

The meso level: departments and institutions

None of this will happen though without some major changes at the meso level. The biggest challenge is for academic departments to give as much recognition to teaching excellence as to research in tenure and promotion, and to have objective criteria for measuring teaching excellence, based on student learning outcomes. This in turn means adopting changes to the curriculum that results in the teaching of measurable ‘future skills.’ Again, it is not that we do not know how to do this, but there are no incentives and many obstacles to doing this. The challenge for departmental and institutional leaders is to remove these barriers and increase incentives for teaching skills, as well as for teaching content acquisition. This will include ways to progressively advance student skills levels in a measurable way from one course to another, as has been done by the Faculty of Computer Sciences at Dalhousie University.

The macro level: governments and professional associations

Governments need to recognise that the growing skills gap is an economic productivity issue. Canada has a dismal productivity record over the last ten years. Developing the future skills that students will need in the future to run successful businesses, learn new skills, and resolve wicked problems is the most cost-effective way to improve productivity . Rather than trying to pick future ‘winning’ industries or innovations and showering companies with government money and subsidies, governments need to invest in our higher education institutions to ensure that they produce the learners with the necessary knowledge and skills to survive in the 21st century. However, that investment needs to be done wisely. It should be focused on those institutions willing and able to change, and be tied to measurable changes in curricula, faculty development, and learning outcomes to reflect 21st century needs. Singapore is already doing this; there is no reason why a provincial government such as British Columbia’s should not go down this road.

The other macro sector that needs to change are the professional associations that give professional accreditation. Assessment should be based as much on students’ performance on so-called soft future skills as on technical or research competence. Without such recognition and encouragement from professional associations institutions will be reluctant to change.

Conclusion

Higher education instructors and institutions will see increasing pressure to change to meet the needs of the last three quarters of the 21st century. They cannot do this on their own. Governments need to recognise this as a major opportunity to increase economic productivity. but it won’t happen without wise investment and incentives for our institutions to change. Doing nothing is not an option if we are to avoid the internal collapse of our higher education systems. I am by nature optimistic. In particular I have faith in our young instructors to adapt and change, but without changes at the meso and macro levels this will be an increasing challenge for them. Rather them than me.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Tony

Exactly, not to mention competition from new entrants and players like Coursera. I explore a lot of these themes in my new book: https://ethicspress.com/products/the-future-of-higher-education-in-an-age-of-artificial-intelligence

Think about Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation being at play here.

¿Cómo investigar la soledad no deseada (SnD), dentro y fuera del sistema nacional de salud que es funcional al modelo de negocio basado en la enfermedad y no en los determinantes sociales para la salud en tiempos de vejez con pobreza sin fronteras? ¿El modelo educativo y de formación pre y pos-universitaria no es funcional al modelo actual de la enfermedad, donde la carga global de la enfermedad está básicamente en los determinantes sociales para la salud el cual representa el 80 % de los problemas de salud y los médicos no los investigan en su consulta diaria. La pregunta es ¿por qué?

RTED LATINOAMERICANA DE GERONTOLOGÍA CLÍNICA Y SOCIAL. Perú ageing 4.0 #haciendomásconmenos