Am I qualified to comment on this topic?

It is with some hesitation that I am publishing this post. I decided to retire completely partly because of the complexity of the issues around the use of AI for teaching and learning, my relative lack of knowledge of the precise ways AI models work, and my horror at the thought of learning (at 85 years old) the necessary mathematics needed to become an expert in this area.

However, I am still asked for my views on this topic. I did co-edit a paper in 2020 (Bates, Cobo, Mariño, and Wheeler, 2020) that called for papers on this topic and I have also carefully read Zawacki-Richter et al.’s ‘Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education: a wide range of papers on the use of AI for teaching‘ published in 2019, which reviewed almost all the papers on this topic up to that time. The general conclusion of the research up to 2020 was that AI was mostly overhyped for educational purposes, doing little more than programmed learning and the testing of comprehension.

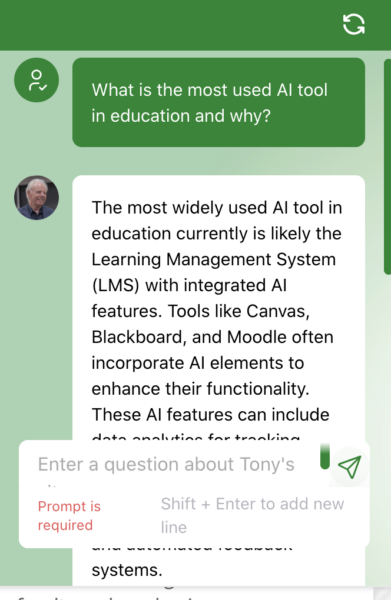

However, that was then and this is now. Since 2020 we have seen the emergence of generative language models such as ChatGPT. This is undoubtedly a significant advance in the use of AI for teaching and learning. I also use ChatGPT, which as you can see sits on the top of each page, offering you answers to your questions on online learning and open and distance education.

So while I cannot claim to be an expert, I do have some knowledge and some views about what universities and colleges should do now, given the current state of AI. I would also like to thank my colleagues Ross Paul, Kjell Rubenson, John Stubbs, and Tom Nesbit for their input to the discussion at a recent chat about this issue over a glass of wine, but I wish to emphasise that what is printed below is entirely my responsibility.

What is different about generative language models

Generative language models such as ChatGPT are a huge advance on earlier applications of AI in education, in that they can put the results of a general Internet search into a comprehensive report in language so fluent that it appears to have been written by a human. However, it is important to understand how ChatGPT and other similar models do this.

The basic process is to work out the probability of the next word in a sentence, based on the input question. To calculate the probability, ChatGPT searches the whole Internet to identify the most common combination and sequence of words on a topic.

Strengths and weaknesses of ChatGPT

- With a big enough data base of whole sentences by searching everything possibly available on the Internet, the result is surprisingly accurate in summarising all past writing on a topic.

- Note that the process is purely mechanistic – there is no ‘understanding’ or conceptual processing involved.

- However, the more ‘original’ a topic, the less valid the ChatGPT response becomes, because ‘new’ topics have fewer words on which to base the search. (ChatGPT admits that it can search materials published only up to two years before its response.)

- Although often appearing comprehensive, ChatGPT responses often lack ‘nuance’, because ‘minority’ statements (i.e statements that appear less frequently) are often lost or dismissed because of their lower probability; as a result, ChatGPT is excellent for dealing with issues where there is widespread agreement over a wide range of sources, or where there is a great deal written about competing perspectives, but not so good at picking up on isolated but perhaps important alternative contributions to a topic.

- ChatGPT does not provide accurate description of sources when asked (probably to avoid charges of copyright infringement) and in any case it draws on all the Internet, not just the main (or most reliable) sources. It is difficult to know then how reliable the summary response is, whether it is based on highly respectable academic journals or just on general chat on Facebook. As with all AI tools, it does not make its algorithms publicly available so it is impossible to know whether responses from academic journals are weighted more highly than comments from Facebook, for instance.

- It is possible to ‘game’ the system by ‘flooding’ a topic (i.e. via social media), so it may magnify popular but inaccurate misconceptions on a topic

- Therefore it is difficult to ascertain accuracy of a response unless you are already an expert on the topic.

- Asking the right questions, and follow-up with further questions, is essential for valid results.

Implications for universities and colleges

- Students (and some academics) will use it and pass it off as their own work.

- It can be very useful in allowing students to get a quick and in most cases an accurate overview of a topic that has had widespread coverage on the Internet.

- It can be very useful for academic research, in providing a quick overview of the literature.

- It can be very useful for developing ‘standard’ curricula for well-researched or well-established subject areas.

- It will force a re-think of assessment practices. AI replaces the need for memorisation, recall and even overall understanding of a topic. Instructors should assume that students will use AI for these purposes (as will people in life outside universities and colleges). This will free up instructors to focus on the areas that AI (so far) is less useful for, namely critical and original thinking.

- AI is not just the most recent over-hyped technology. It is not going away and over time will become more powerful, especially once AI programs incorporate self-learning (or, more accurately, self-correction) and cognitively-based algorithms (i.e. algorithms that mirror human thinking processes).

- However, ‘managing’ AI will be difficult, mainly because of its lack of transparency. For obvious ethical reasons, in education it is absolutely essential to know how AI arrives at its responses. This means making the algorithms – or at least the overall process being used – transparent.

What should universities and colleges do?

1. Use AI – but intelligently.

There are three separate areas where AI will be useful, and each will need a different response:

- teaching and learning

- admissions and other student services

- administration.

2. Teaching and learning.

This is the most problematic area in terms of change, and the management of learning:

- Develop experts in AI for teaching and learning: understand how the technology works, and its strengths and weaknesses for teaching and learning. Such expertise needs to combine pedagogy and IT skills. Embed this expertise in Centres for Teaching, Learning and Technology, and have a program to educate faculty. You can’t manage it if you don’t understand it.

- address assessment issues first. This is best done by avoiding assessment based on recounting facts, ideas, principles that can be written down. AI will do this better than most humans. Set assignment questions that require originality on the part of the student, such as solving uncommon or unique problems, and/or drawing on personal experience, etc. This means focusing on higher level educational objectives such as evaluation, critical thinking, and creative thinking (which is after all what universities should be about). Focus more on oral and continuous assessment than written and summative tests, so instructors can see the development of individual students.

- embed AI in teaching. Encourage students to use (and identify) it for doing research on projects, then get them to indicate the strengths and weaknesses of the AI answer. What would they add to or change in the AI answer? This will better prepare students for using AI tools when they enter the work force.

3. Admissions and student services

- AI, especially when combined with learning analytics, can be very useful for helping identify students in need of help, and subject choice for students, but be very careful when using AI. Test for inherent bias in the tools and correct for it. Have an internal review committee for admissions policies that monitors the use of AI. Again, someone in the Registrar’s Office and/or in Student Services needs to be an expert on AI and the AI tools that could be useful (or dangerous) for students and administrators.

4. Administrative areas

- AI is/will be extremely valuable and useful for financial, legal and marketing work and could save substantial money in replacing human workers, thus freeing up more resources for teaching, learning and research. However, there needs to be an AI specialist on board who understands both the potential and limits of AI in these fields.

Conclusion

AI is not going away and will become even more powerful over time. Senior management, instructors, and administrators need to understand how and why AI can be valuable and its limitations. However, becoming comfortable with AI requires a steep learning curve. Institutions should not leave this to happenstance. There should be a systematic approach to providing training in AI to those who need it, and there should be a clear structure (such as committees) that involves all stakeholders, so that decisions about the use of AI are understood and accepted.

This might take the form of a task force or special committee, but as with all major new technologies, decisions need to be taken at the right level by the right people. Faculty and instructional designers, in consultation with students, should decide on its use for teaching and learning. But ignoring AI and hoping it will go away is not an option.

References

I am unable to give a full set of references on this topic, just the ones referred to in this article.

Bates, T, Cobo, C., Mariño, O. and Wheeler, S. (2020) Can artificial intelligence transform higher education? International Journal of Technology in Higher Education, Vol. 17, No. 42

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marin, V., Bond, M. and Gouverneur, F. (2019) Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education – where are the educators? International Journal of Technology in Higher Education, Vol. 16, No. 39

For an article on assessment design, see

Hendricks, C. (2024) Assignment and assessment design using generative AI A.I. in Teaching and learning, Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology, University of British Columbia

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Well put, as usual. Thank you for summarizing so effectively my rather muddled thoughts about the future of AI.

I would add that in teaching AI has the strong possibility of providing tutoring-level assistance in subject basics at all educational levels beyond elementary education. I see many of the lower-level STEM and language classes (maybe writing too) replaced by more effective, because personalized, low-cost, dedicated AI’s.

Thanks, James – and great to hear from you again. Yes, I agree about ‘standard’ lessons being replaced largely by AI, but I would add the students should always have the opportunity to contact a human teacher when needed.

This is a crucial reminder that AI’s growing influence requires proactive engagement from all educational stakeholders. Establishing structured training and collaborative decision-making ensures that institutions harness AI’s potential effectively while addressing its limitations. Ignoring AI would mean missing out on opportunities to enhance learning and administration, making it essential for leaders, educators, and students to work together in navigating this transformation.

AI has made everything simple and I am afraid that it weakens human’s critical thinking.

How can institutions ensure that faculty and students are equipped with the necessary skills to effectively integrate AI into their learning and teaching processes? Given the rapid pace at which AI technology evolves, should universities be focusing on a continuous professional development model to keep up with these changes, or is it better to establish a standardized curriculum for AI education? Visit us Telkom University Jakarta

In response to this question, Khairun, I don’t know. In general I would approve a continuous professional development model, because AI is rapidly changing, so any ‘standardised’ curriculum for AI is going to be rapidly out of date.