I am writing an autobiography, mainly for my family, but it does cover some key moments in the development of open and online learning. I thought I would share these as there seems to be a growing interest in the history of educational technology.

Note that these posts are NOT meant to be deeply researched historical accounts, but how I saw and encountered developments in my personal life. If you were around at the time of these developments and would like to offer comments or a different view, please use the comment box at the end of each post (but please don’t sue).

Plans for the Open University

I was on a three-year contract from 1966 to 1969 with the National Foundation for Educational Research in Britain. My research focused on the internal administration of the new comprehensive high schools that the Labour government was promoting. My contract and the work was coming to an end, so I began to look elsewhere for work in 1969. I was 30 years old.

There had been quite a bit of discussion in the British newspapers about Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s plans for a University of the Air. At that time, despite the rapid growth of universities in Britain following the Robbins report in 1963, less than 8 per cent of school leavers went on to university. There was also at this time a shortage of school teachers, and teacher training colleges were being rapidly expanded, but no undergraduate degrees in education were available in Britain at that time.

In the five years between 1963 and early 1969 the idea of a ‘University of the Air’ had developed into a proposal for an open university that would combine correspondence education and broadcasting. It was to be called an Open University, and as well as its proposed use of broadcasting for teaching, it was to be open to all, with no prior qualifications required. It was sometimes called ‘The University of the Second Chance’ for those that were not able to go to university on leaving school.

Getting the job

I was unable to go to university when I finished high school (that’s another story), and spent two years miserably working in low-paid clerical jobs (including getting fired by a bank because I lost the front door key of the branch I was working in). I eventually got to go to university mainly through the kindness of a bureaucrat at the London County Council who helped me get a grant. As a result, the idea of an open university really appealed to me, so when a job advertisement appeared in the summer of 1969 for a research officer at the newly created Open University, I jumped at the chance.

I was called for an interview. The OU had just received its charter and the Planning Committee and the few people who had already been appointed were working out of a beautiful Georgian house on Belgrave Square. (Most of the houses are now mainly occupied by foreign embassies). On my interview panel were the Vice Chancellor, Professor Walter Perry, and a couple of Deans (Mike Pentz from Science, and John Ferguson from Arts).

The University was scheduled to open to students in January 1971. In the meantime, the National Extension College in Cambridge was working with the BBC to develop multimedia Gateway courses that students could take as preparation for the coming OU courses – and which would also test the design of combined print and broadcast courses before the university started. The OU’s Planning Committee was aware that there needed to be regular and systematic institutional research on the effectiveness of the Open University’s teaching methods, given the controversy surrounding its establishment, which at the time was deeply criticised by the opposition Conservatives.

Only one research officer post was advertised. This was actually offered to Naomi McIntosh, a researcher with strong social survey research experience. However, the appointment committee was sufficiently impressed by my application that they also offered me a position as a second research officer reporting Naomi. The mandate was pretty broad: investigate the effectiveness of the Gateway courses and distance education in general.

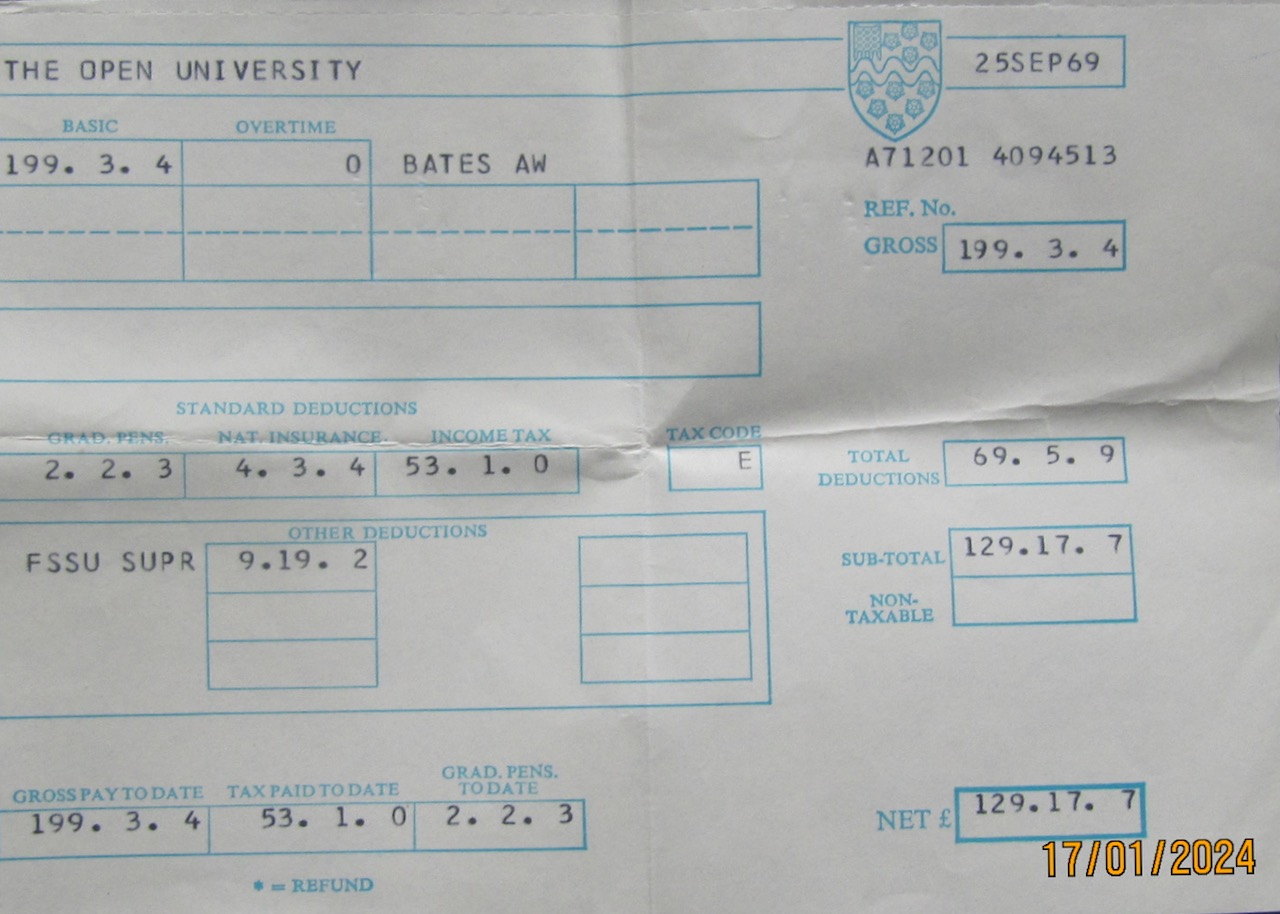

I started in September, 1969, at an initial salary of £2,400 a year – but then beer was 10 pence – two shillings – a pint. The equivalent annual salary in Canadian dollars would be about C$4,000, and the glass of beer would be 20 cents. I was the 20th person to be appointed to work at the Open University.

Defining open education

Not long after I was hired, I was invited with other staff members to the formal inauguration of the Open University at the Guildhall, London, the ancient building used for major ceremonies in the City of London.

The Chancellor (equivalent to Board Chair) of the Open University was Lord Crowther, who gave a very short inaugural speech which really resonated. He said the university would be open:

- to people, with its open admissions policy,

- open to methods, such as broadcasting and print and ‘other technologies yet to come’,

- open to ideas, and

- open to time and place, where students could learn and where instructors could teach from anywhere at any time.

This definition of open education has certainly stood the test of time for me.

The start of the Open University

Naomi and I shared an office initially in Belgrave Square, but most of our time was spent travelling to and from the National Extension College in Cambridge to liaise with the NEC, and to collect and analyse data.

The plan was for the Open University to move to brand new premises to be built on the grounds of an old country manor house, Walton Hall, in the new city of Milton Keynes.

Milton Keynes was designed initially to deal with the overflow of demand for housing in and around London. Many of the first residents of the new city were from the clearance of run down buildings (slums) in the east end of London. Walton Hall itself was an 18th century manor house, which would be the administrative headquarters of the university. Everything else was to be built from scratch. It was in essence a green field site for the new university.

The key political driver for the establishment of the Open University was the Minister for the Arts, Jennie Lee (the wife of Aneurin Bevan). She was able to leverage the necessary money for the purchase of the land and for the capital investment in the buildings and facilities. However, the timescale was very short: less than 18 months from the securing of the funding to the opening of the new buildings. The first students (20,000 in all) would start on four foundation courses in September, 1971.

One day, I was in our office at Belgrave Square, when the newly appointed Purchasing Officer burst into the room. John was in his late twenties and always looked harassed and worried. As he was around the same age as me and equally bemused by what was happening all around us, I had become quite friendly with him.

“Tony – you won’t believe what just happened. I got a memo from Walter Perry to purchase half a million pounds worth of office furniture and equipment for the site at MK. I went in to see him with different designs for the desks and chairs and office equipment for his approval. He just looked at me and said: ‘I’m not buying bloody furniture – that’s your job. You decide. Just make sure it’s there in time – and make sure it will last for at least 10 years. God knows when we’ll get the money to replace it.’”

For several years after the move to the Walton Hall campus, whenever I was in a meeting with John, I would say; ‘John: these are god-awful tables and chairs’ – but, in reality, they were perfectly suitable. It was though a good lesson in delegation.

Different media, different responses

Naomi designed a number of questionnaires to get feedback from the students taking the NEC Gateway courses. I helped with the analysis and report writing. As well as Likert-scale questions asking for students’ responses on a seven-point scale, many questions had space for open-ended comments from the students.

In doing the analysis of the open-ended comments, I was struck by the difference between the student responses to questions about the printed texts for the courses, and their responses to the accompanying broadcasts. In general, the responses about the printed study materials were calm, thoughtful, and analytical, pointing out areas of difficulty or where the materials were particularly helpful. For instance: ‘There was quite a bit of reading this week, but it was interesting.’

The responses on the other hand to the broadcasts were quite different. They tended to be much more emotional, with extremes of high praise or very emotional criticism. For instance: ‘Why are you wasting my time with this nonsense? The program may have provided a nice visit to America for the BBC crew, but it was of absolutely no help in explaining the economics of the Depression,’ or (for the same program): ‘This was a fascinating exploration of the New Deal in America and its impact on the economy and everyday life of working people. Great stuff.’

There’s something here, thought Tony. The two different media of print and television were resulting in qualitatively quite different responses from students. Since the Open University would be spending more than a fifth of its budget on the broadcasts, it might be worth spending a little time and money on evaluating the effectiveness of the programs, I thought.

Multi-media course design

The Planning Committee and senior management recognised the need to bring in a systems approach to course design. For the first four foundation courses, there would be more than 5,000 students on each course. The aim was to have specially designed print materials that incorporated the latest research into effective learning. Walter Perry in particular wanted to ensure that these printed materials were not only of the highest academic quality – a model for other universities – but also were attractive and easy to learn from, as many of the students taking foundation courses would not necessarily have completed high school. Several private consultants specialising in systems and instructional design had been hired to help with the initial course design strategy. These included Gordon Pask, Brian Lewis and Macdonald Ross.

Another feature was the establishment of course teams to design the first courses. Since the four foundation (first year) courses in arts, social science, science, and technology were meant to be interdisciplinary, this required professors from different disciplines within the faculty to work together on the same teams, supported by educational technologists. The BBC meantime had recruited graduates in each of the disciplines and trained them as television and radio producers, so there was at least one BBC producer on each course team.

In 1970, a decision was made to establish an Institute of Educational Technology to help support the design of the first academic courses. The Institute of Educational Technology would hire specialists in learning design, as well as specialists in graphic print design. David Hawkridge was appointed as Director.

A focus on broadcast media research

I managed to persuade Walter Perry and David Hawkridge that there was a need for specialist research that would focus initially on evaluating the BBC broadcasts on the OU foundation courses. Naomi and I were moved from contracts to full academic staff, and I started in IET in 1971 as a Lecturer in Media Research Methods, reporting directly to David Hawkridge. At the same time Naomi McIntosh established the Survey Research Group, whose job was to collect and analyse data on Open University students once the first courses were opened.

The BBC sent me on a television producers training course at Shepherds Bush in London so I would understand better the production process (my final project was a television program about the Battle of Alam Halfa, which set up Montgomery’s victory at the Battle of El Alamein.) I went to the Imperial War Museum to research old film and artefacts for the program.

Early in 1970, the first new buildings, set to house the Faculty of Arts and the Institute of Educational Technology, were ready for occupation. Naomi and I were among the first to occupy the IET building. On my first day, I drove to the car park, but getting to the building was a challenge. The whole area was a sea of mud due to the construction. On my arrival at the door to the building, I was given a pair of slippers by a security guard and asked to change into them. “Please leave your shoes here in the lobby and wear these slippers all the time you are in the building. The carpets are brand new” (thanks, John) “and we need to keep them clean.”

This was the start of almost 20 years research on the impact of media on student learning at the Open University.

Up next

My next blog post will focus on my work with the Audio-Visual Media Research Group at the Open University between 1971 and 1980, and its impact on broadcasting policy, production methods, the impact of audio and video cassettes, and student learning, and the lessons from this research that are still relevant today.

Further reading

Perry, W. (1976) Open University Milton Keynes: The Open University Press.

An excellent account not only of the actual events in the establishment of the Open University, but also of the politics, policies and strategies that resulted in one of the most successful innovations in higher education.

Weibren, D. (2015) The Open University: A History Milton Keynes: Manchester University Press.

This takes a longer view of the history of the Open University, up to about 2014. Looks more closely at the teaching methods used and its changing relationship with the rest of the UK higher education system. Reproduces some really great cartoons about the Open University, especially in its early days.

I will refer to other ‘histories’, such as Martin Weller’s ’25 years of Ed Tech’, as I progress through this series of blog posts.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Personal histories are my favorite kinds of research, so this is very much appreciated, especially given your being there at the start of the Open University. I only got a week on campus in 2014, housed in the Jennie Lee building.

Lord Crowther’s description of Open is one worth returning to. What was also evident is that era of overwhelming commitment from the top levels along with granting much independence trusted to those to carry out the work.

I’m also reminded of that 1970 era of educational technology, well not from first hand experience because I was 7! But my second cousin did an Ed Psych PhD at Arizona State University, and when David shared his stories of that era he described what they were really doing as research into educational technology. When I asked what was the technology of highest interest, he said it was 16mm film.

Thanks for this whole series, Tony. I’m reading them all.

Great reading Tony and I too plan to write an autobiography of my time at the OU and what I did (started 1982) now I have retired. One small correction on this first instalment – the first four Faculties and hence foundation courses in 1971 were science, social science, arts and mathematics – technology became the fifth in 1972. This was because Geoff Hollister, the first Dean of the Technology Faculty, had been interviewed for the Science Dean but argued that a broad based more applied curriculum was also needed given all the technological developments that were happening. Walter Perry seemingly agreed and so a fifth Faculty was established. For context I was the sixth Dean of the Technology Faculty.

Thanks so much for writing (and publishing) what I’m sure will be an epic series.

I spent 33 years at Walton Hall, beginning as a publishing editor, and finally working in communications. And my last role was as Director of External Relations in Open University Worldwide – a very grand title for the activity of building international relationships and partnerships.

I will be particularly interested to see how you perceived the participation of academic editors in course teams, and the part we played in making OU materials accessible and high quality for a mass audience.

Tony, I read this fully whilst sitting in a cafe in Portland ahead of a graduation ceremony at HMP The Verne. As an AL with the OU of a mere 10 years standing, I was struck by your “university of second chances” quote which seems very apt today! I wonder whether you might grant me permission to use it in a speech I’ve been asked to give at another prison graduation ceremony next month? I would reference you of course.

It is nice that there is a history segment, one period, a strong experience of working at the University of UK. Step by step. Generations should know, that nothing is accidental. Everything has roots.

I started my learning at the University of Serbia, at TMF Faculty, started as a technician in the Foundry in Topola, 60 kilometers from the place of study, Terku shift. Putovana every morning Autobis for Belgrade, on lectures and exercises. Commitment, all of the heart. Here are me and healthy in 76 years, a doctor of technical sciences, I still deal with science on materials. I want people to motivate. If you have a goal, internal motivation, you will arrive, for sure. Good luck. Olivera Novitović PhD. professor

Пошаљи повратне информације

Бочне табле

Историја

Сачувано

Wonderful story, Olivera, especially given all the horrors of the immediate post-Yugoslav era.