The context

I am continuing the process of updating the third version of my open textbook, Teaching in a Digital Age, to take account of developments since the second edition in 2019, including the impact of the pandemic.

My original version had a substantial section on the differences between synchronous and asynchronous learning, none of which I really need to withdraw, but I have made some changes to strengthen the sections on the different affordances – or strengths and weaknesses – of both for teaching and learning, as a result of lessons from Covid-19.

As usual, before I finalise the final version, I am hoping to get some feedback or suggestions from readers of this blog on how to improve further this section. The text in blue reflect changes from the previous edition. This section was preceded by a discussion of ‘affordances’ of media and the difference between ‘live’ and ‘recorded’.

The new version

7.4.2.2 Synchronous or asynchronous

Synchronous technologies require all those participating in the communication to participate together, at the same time, but not necessarily in the same place.

Thus live events are one example of synchronous media, but unlike live events, technology enables synchronous learning without everyone having to be in the same place, although everyone does have to participate in the event at the same time. A video-conference or a webinar are examples of synchronous technologies which may be broadcast ‘live’, but not with everyone in the same place. Other synchronous technologies are live television or radio broadcasts. You have to be ‘there’ at the time of transmission, or you miss them. However, the ‘there’ may be somewhere different from where the teacher is.

Asynchronous technologies enable participants to access information or communicate at different points of time, usually at the time and place of choice of the participant. All recorded media are asynchronous. Books, DVDs, on-demand You Tube videos, lectures recorded through lecture capture and available for streaming on demand, and online discussion forums are all asynchronous media or technologies. Learners can log on to or access these technologies at times and the place of their own choosing.

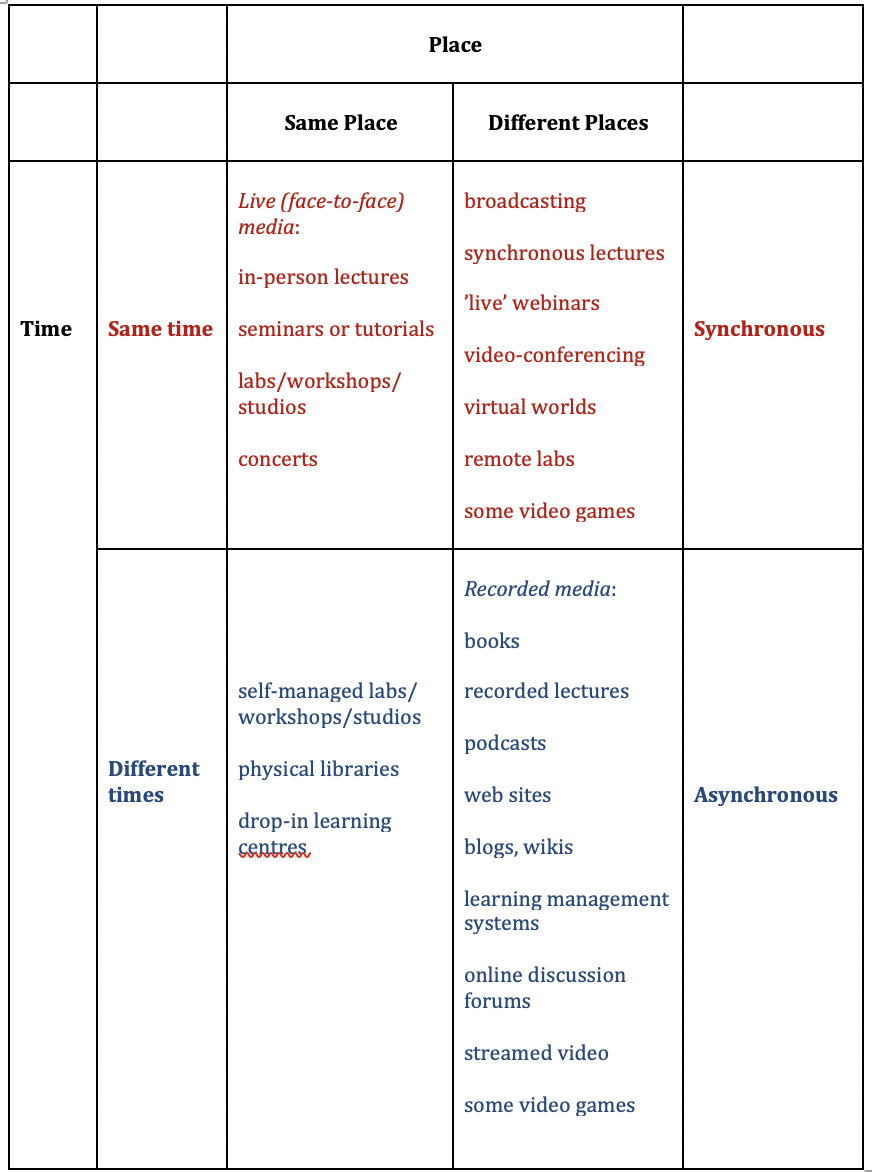

Figure 7.4.4 illustrates the main differences between media in terms of different combinations of time and place.

Figure 7.4.4 Synchronous and asynchronous educational media (examples)

7.4.3 Why does this matter?

Synchronous and asynchronous technologies have different advantages and weaknesses (affordances) for teaching and learning.

7.4.3 1 The affordances of asynchronous technologies

Asynchronous technologies have been used in online learning for at least 30 years (and in the case of older media such as books for much longer). Because asynchronous online learning has had to justify itself in comparison with in-person learning, we have more practice- and research-based evidence of the affordances of asynchronous online learning, as well as well-defined quality standards.

Overall there are major educational benefits associated with asynchronous or recorded media, because the ability to access information or communicate at any time offers the learner more control and flexibility. The educational benefits have been confirmed in a number of studies. For instance, Means et al. (2010) found that students in general did better on blended learning than in-person learning, because they spent more time on task, as the online materials were always available to the students.

Research at the UK Open University found that students much preferred to listen to radio broadcasts recorded on cassette than to the actual broadcast, even though the content and format was identical (Grundin, 1981; Bates at al., 1981). However, even greater benefits were found when the format of the audio was changed to take advantage of the control characteristics of cassettes (stop, replay). It was found that students learned more from ‘designed’ cassettes than from cassette recordings of broadcasts, especially when the cassettes were co-ordinated or integrated with visual material, such as text or graphics. This was particularly valuable, for instance, in talking students through mathematical formulae (Durbridge, 1983). The Khan Academy is a more modern approach but using similar principles of using voice over graphics.

This research underlines the importance of changing design as one moves from in-person to asynchronous technologies. Thus we can predict that although there are benefits in recording live lectures through lecture capture in terms of flexibility and access, or having readings available at any time or place, the learning benefits would be even greater if the lecture or text was redesigned for asynchronous use, with built-in activities such as tests and feedback, and points for students to stop the lecture and do some research or extra reading, then returning to the teaching.

The ability to access learning materials on demand (recorded lectures or webinars, learning management systems, web sites, social media) is particularly important for increasing access and flexibility for learners, especially those working as well as studying, for those with young families, or for students with long commutes. Thus there should be clearly justified pedagogical benefits that could not be provided by the use of technology if students must be present either in the same place or at the same time as an instructor. In particular, what are the social or pedagogical reasons why students should come to the school or campus or be present at a set time when so much teaching and learning can now be done asynchronously?

7.4.3.2 The affordances of synchronous technologies

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, there had been little research on the affordances of in-person lectures compared with online teaching. To some extent, in-person lectures or seminars were considered the gold standard. There was no need to identify its advantages over online learning. However, Covid-19 and emergency remote learning resulted in a number of lessons being learned, both about the affordances of lectures in general, and also of the limitations in moving lectures online.

Couey (2022) has set out some of the advantages or affordances of synchronous, in-person learning::

- a dedicated space and time where students and instructors can meet to discuss learning material develops a sense of companionship and can foster an environment conducive to learning

- students are able to discuss complex material together in order to gain a better understanding in real-time, and instructors have a greater finger on the pulse to know what they need to focus on

- students can interrupt the lecture to ask questions which can lead to a more narrow, targeted discussion.

- students can break out into smaller groups to collaborate with each other. Some of the best learning opportunities come from these spontaneous questions and discussions

- teachers can feel the pulse of the room and have a much greater idea about which parts of the lesson students understand and which they might need to spend more time reviewing.

Up until 2019, most online learning was asynchronous, (at least in North America), built around the use of learning management systems. In Canada in 2018, nearly all institutions (93%) were using an LMS for online learning (Johnson, 2019). This suited students who were fully distance learners in particular, who were often also often working full-time, or were at home with young children. Courses were deliberately designed to take advantage of the affordances of asynchronous learning.

However, the use of synchronous video-conferencing technologies such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, BigBlueButton, and so on was increasing rapidly to the point where just over two-thirds of all institutions were also using such synchronous technologies, usually in parallel with an LMS (Johnson, 2019).

In the Spring of 2020, when nearly all post-secondary education was abruptly moved online because of the Covid-19 pandemic, most courses that had not been originally designed for online learning were also moved online. However, because this was an emergency (hence the term emergency remote learning), the main technology used was synchronous video-conferencing for several reasons:

- Instructors were able simply to transfer their familiar in-person lecture methods online.

- The technology was relatively easy to use without extensive training.

- Most institutions already had a license for such technology.

- Lastly, there was no time for instructors to consider re-designing courses.

So during the pandemic, the dominant online teaching method was synchronous lecturing. This did not go down well with students for a number of reasons. The main concerns with synchronous lectures used for emergency remote learning identified from a number of different research studies (Bates, 2021) were as follows:

- too much passive screen time

- too little student interaction either with the instructor or with other students

- work overload, because instructors were often giving students extra work on top of the lectures

- most students preferred to watch the recordings of the lectures but sometimes students were not given access to recordings of the lectures, because the instructor wanted students to be ‘present’ for questions and discussion

- lack of the social aspects that result from being on campus (although this was not really possible anyway during the pandemic).

This suggests the need for a number of adaptations of in-person lectures when moved online:

- Probably the most important lesson from the pandemic was that moving classroom lectures online without considerable adaptation is not an effective way to teach.

- Some instructors made good use of the break-out rooms in Zoom, for instance, allowing students to have synchronous discussion or do collaborative work, then returning to report to the main session.

- Research suggests instructor presentation should be limited to 15 minutes or so followed by a break for questions and discussion.

- It is really important for students to have access to a recording of the lecture.

- Lectures should be used in conjunction with asynchronous online activities, such as online discussion forums, online reading or research.

- Instructors should carefully consider student workload, especially if combining synchronous and asynchronous learning activities.

- it should be remembered that many students opt for online learning because of its flexibility, which synchronous lecturing considerably retricts.

All this suggests that wherever possible, instructors should consider redesigning the whole course if it is to go online, and the rest of the book looks at ways to do this.

7.4.4 Conclusion

The ability to access media asynchronously through recorded and streamed materials is one of the biggest changes in the history of teaching, but the dominant paradigm in higher education is still the live or synchronous lecture or seminar. There are, as we have seen, some advantages in live media, and direct inter-personal contact, but they need to be used more selectively so as to exploit their unique advantages or affordances, and should also be combined with asynchronous media. Indeed, for online learning, asynchronous should be the default model, but supported by synchronous teaching where necessary and appropriate.

This section will be followed by a section on the educational differences between broadcast and interactive media

Over to you

I am open to any observations or comments, but I also have some of my own questions.

- Robert Ubell has criticised the use of the terms ‘synchronous’ and ‘asynchronous’ as they are not likely to be familiar to most instructors. (See also Joshua Kim on this). Do you agree, and if so, what alternative words or phrases would you suggest?

- Are there other affordances of synchronous and asynchronous learning that I have missed or are there any that you disagree with?

- Do you agree with the suggested adaptations that I think are necessary when moving lectures online?

- Does it need more adaptation for those working in the k-12 sector?

- Do you agree with my conclusion or is it too general: ‘for online learning, asynchronous should be the default model, but supported by synchronous teaching where necessary and appropriate.’?

- Is the distinction between synchronous and asynchronous teaching and learning useful, or are we trying to count the number of angels that can dance on the tip of a pin?

I will shortly post the next section on the differences between broadcast and interactive communications media.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Here is my feedback:

– In the field of technology enhanced learning we use several unknown terms. In my opinion asynchronous and synchronous are easy to explain.

– Is the combination different time, same place possible? Imho it is. This is when learners study online content at their own pace, complete assignments or self-tests, etc. You often see this applied in K12 education en vocational education and training (e.g. station rotation model). However, this is quite challenging.

– Learners can speed up videos. As a result, learners often learn better. See for example: https://3starlearningexperiences.wordpress.com/2022/04/04/videos-for-learning-beep-beep/

– Indeed, learners have opportunities to pause and do additional research or study sources and then return to the online learning content. You thus have the opportunity to broaden and deepen your knowledge.

– You can use synchronous online learning indeed to develop a sense of companionship and foster an environment conducive to learning. However, this is more difficult to achieve online than physically. You have less insight into non-verbal signals and less opportunity for spontaneous meetings (e.g. at the coffee machine). But if you if it is (harly) impossible to meet physically, synchronous online is certainly an option.

– The immediacy has added value compared to asynchronous online learning.

– I miss the argument that synchronous online learning can lead to more interaction. For example, if you take notes of questions in a physical room – without technology – it is usually the same learners who are speaking. If, for example, you list questions during a live online session via chat, then many more learners can respond.

– Social media are one click away. Learners can easely be distracted by social media during synchronous online learning.

– Synchronous online learning is technically more challenging. Learners do not always have the right facilities for synchronous online learning, especially when a whole family needs to participate in live online sessions at the same time.

Many thanks, Wilfred – you raise some great points. I agree that there are instances of same place, different times: use of a physical library for instance. And definitely, student control (asynchronous) when studying, such as stopping and starting, has been shown by research to be more effective than synchronous learning. And again you are right: research shows that in synchronous classes of 100 or more, the same people (roughly 10 per cent) usually ask the questions. I have found student contributions to asynchronous online discussion more widespread, although you still have to work to get all to participate.

Hi Tony,

I think you are missing one development over Covid. Online educators who had previously been all asynchronous started adding zoom or team webinars for multiple reasons. Some of it was related to building community when students were stuck at home. Some of it was related to teaching difficult concepts online like research methods or math or science. I see this as happening predominantly in graduate education. We here at Empire State college built an EdD in educational leadership and change which was launched during Covid which was supposed to have a low residency f2f component. We did one virtual residency in year one and will move to f2f in year two. But we also added synchronous teams meeting every other week for each doctoral class (built on successful we had seen at another institution.

So my point is that I think that particularly graduate education is in the process of evolving into a predominantly asynchronous with a planned synchronous through webinar or residencies. I see this as a positive direction and supporting one of your final points, but with a different way of getting there. Colleagues are doing research on this model, which I will share with you in two weeks when we are both keynoting at the digital Ed conference in Galway. Looking forward to seeing you!

Hello Tony,

Dominic here, from Hanoi.

I have some brief comments, which may be useful.

1. Dependent or independent learner. The degree of independence acquired by the learner is critical in determining how much benefit a student may gain from asynchronous, remote classes as against face-to-face classes. So affordances vary from primary to tertiary and postgrad education.

2. Learning culture. In VN it is still common to see very passive learning, where there is virtually no dialogue and no functioning interactivity. Students are wedded to a classroom culture where information is distributed, one way, and noted, remembered or discarded. Typically, there are no questions, no discussion. Students are loath to challenge teachers.

3. My experience at my Vietnamese university during Covid was emergency switch to Zoom, supported by Classroom as LMS. I found Classroom a bit stale and simply set up chat groups on Facebook Messenger, which all my students use frequently anyway.

4. As we discovered at the UKOU, a long time ago, simply filming a F2F lecture and streaming or recording is desperately unsatisfactory. It’s all about what best suits the medium, or channel of communication, and once a student is looking at a screen rather than sitting at the back of a lecture theatre, many variables exist.

Those are my instant thoughts, and I look forward to seeing your next instalment.

Thanks, Dominic and good to hear from you. Totally agree with your points, especially the first one.

However, independent learning is a skill that can be taught, as well as being an attitude. That’s why I think hybrid or blended learning will be important, especially at undergraduate level, as it introduces students more gently to taking responsibility for their own learning.