Downes, S. (2022) Connectivism, Half an Hour, 9 February

In an earlier post I gave an overview of Stephen Downes’ latest update of his theory of connectivism. My first post was purely factual, if selective. Here I will give my views on the theory, at least as the theory stands at the moment.

It’s taken me a month to do this because each time I started, I felt deeply dissatisfied, both with Downes’ theory and with my response to it. I really do believe that his theory is an important attempt to develop a theory of learning fit for the 21st century, but it has so many problems I really didn’t know where to start.

In the end, after a lot of reflection, I came to the same opinion as the psychologist Ebbinghaus about von Hartmann’s theory of the unconscious: ‘what is true is not new and what is new is not true.’

The importance of the theory

Connectivism is really the first attempt to build a theory of learning that takes into account the digitalisation of knowledge, and recent developments in computer science, neuroscience, and research into artificial intelligence. These are such major developments over the last 20 years that they do require a major reconsideration of theories of learning.

The issue then is whether or not this is a satisfactory theory of learning for a digital age, and whether or not it is ‘satisfactory’ will depend not only on its inherent persuasiveness, but also on what you think the main value or purposes are of a theory of learning.

Since we are all likely to differ somewhat on these criteria, this will of course be a deeply personal review of the theory. As always, I suggest you read Stephen’s article in full, and come to your own conclusions. You will probably find, as I did, that this is a difficult but worthwhile exercise.

Downes’ theory of connectivism

The following from Downes’ article captures the essence of connectivism:

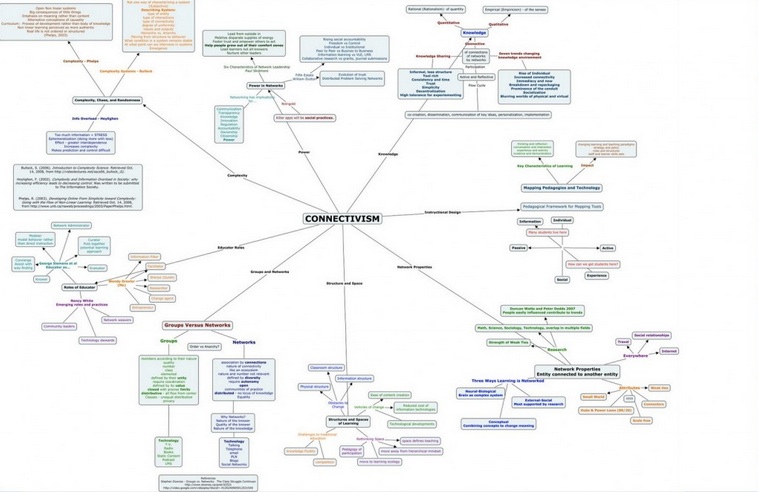

Connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks….

Learning is a thing that networks do, it’s a thing that all networks do, and arguably a thing that only networks do……

Connectivism to me is a non-representational theory. That makes it quite different from other theories. What I mean by that is there’s no real concept of transferring knowledge, making knowledge, or building knowledge. Rather learning and knowing are descriptions of physical processes that happen in our brains….

A key question is, what makes these artificial neural networks work? In the field of artificial intelligence, the answer is arguably trial and error….

in artificial neural networks it [learning] occurs as a result of ‘training’…..The term ‘training’ has a poor connotation in the world of education because it signifies rote and repetition, as in vocational training, without reference to deeper understanding or cognition. But that isn’t exactly the meaning in use here. ‘Training’ in this context is just the process that a person goes through, or even more accurately, the process that a network goes through, during repeated iterations of experience, to acquire the configuration (the set of connections, and the set of weights of connections) appropriate to whatever it’s experiencing.

What is learning?

Understanding – and agreeing to – what learning actually is, is a fundamental first step in any theory of learning. Indeed, it need go no further than that. What you do with such a theory is another matter (but an essential step in any system of education), but if you can’t agree on what learning is, then developing any educational strategy is fraught with challenges.

Downes argues that learning and knowing are descriptions of physical processes that happen in our brains…..We’re working with a physical system, the human body, composed of physical properties, and in particular, a neural net that grows and develops based on the experiences it has, in the activities, and results of those activities it undertakes.

I would not disagree that learning itself is fundamentally a physical process. The brain takes input through various senses, and these form patterns or networks of neural connections. Learning is really a change in those connections as a result of the new sensory inputs. However, this does not help much in understanding what has been learned, or how it has been learned. It’s like saying a television drama is a dynamically changing set of pixels. But what about the plot, the characters, the setting?

This gets us straight into Cartesian dualism. Descartes argues that there are two kinds of foundation: mental and physical. Descartes states that the mental can exist outside of the body, and the body cannot think. In my view, this too is too simple. There is clearly a direct link between the physical actions of the body, including the brain, and what and how we learn. Any theory of learning though needs to go beyond the mechanics of physiology.

Learning is really about consciousness and thinking, rather than wondering what neurological reactions are happening, and how neurons or nodes in a network are connected. It is these psychological aspects of learning that educators and learners themselves are most concerned with. Neuroscientists are very careful not to make any direct links between specific neural network activity and observable cognitive behaviour, particularly in causal terms, so any theory of learning needs to explain these psychological manifestations of physiological activity. You need to look at the action on the screen, not the patterns of 1s and 0s that create a computer program.

How does learning take place?

Downes dismisses most other existing theories of learning. Other learning theories talk about the activities that are set up and organized by an instructor or a teacher rather than what learning is like from the perspective of the individual.

This is a good example of the many statements that Downes makes that are factually incorrect. Several theories of learning have been based on close observation of learning from the perspective of the learner. For instance, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development was based on observations over a long period of time of hundreds of children playing. One of Piaget’s basic research assumptions was that the best way to understand children’s reasoning was to see things from their point of view. He showed clearly that children go through different stages of mental development. This is critical in understanding how we develop concepts and ideas and in particular that learning is dynamic and incremental.

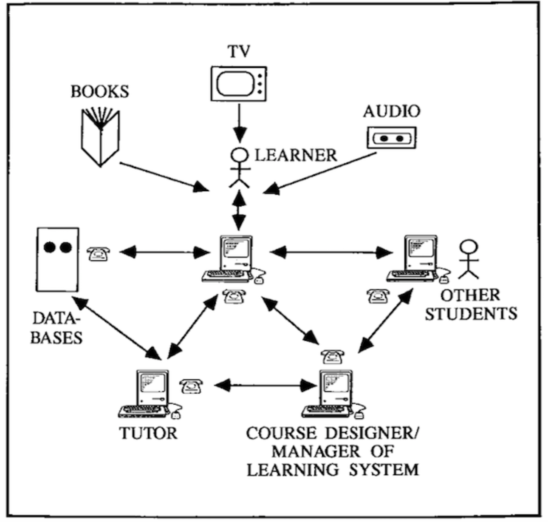

Also, the concept of networked learning goes back more than 40 years. Hiltz and Turoff wrote a book about networked learning in 1978. This was about how networked computers could facilitate learning through communication between students and instructor. I wrote a paper in 1986 in which I published the following:

Much has been learned about how to improve this kind of networking for learning over the years (see particularly Harasim’s ‘Learning Theory and Online Learning’, 2017), all based on human communication through computer networks.

Downes later states that he ‘guesses’ that learning takes place mainly by trial and error. However, besides being extremely behaviourist, this is a not very efficient way of learning, what most education is (or should be) about is ensuring the conditions for effective learning are developed.

And this is where the real problems of the theory start to show. Downes deliberately intends his theory of learning to be essentially mechanistic (or electronic), certainly materialistic. There is a lot of discussion of how machines learn (AI) without questioning whether this is the same or might be different from how humans learn.

Also there are serious questions about his explanation of how networks learn. He and Siemens talk about nodes in a network (which may or may not be humans) and that nodes send ‘signals’. I get that the whole may be greater than the sum of the parts, but what do the nodes actually contribute to the network other than sending signals? In concrete terms, if we look at a connectivist MOOC, individuals in the network contribute ideas, thoughts, knowledge to the network – where does this knowledge come from? It comes from what the individuals have learned prior to participating in a network. Much human learning clearly takes part from outside a network.

Again, I do not disagree that learning through and within a network is one way to learn – and to generate knowledge – but it is not the only way. I can learn from reading a book. My mother taught me to read before I went to school. Sure, there are networks involved at some degree of distance (you need authors and publishers for a book, and how did my mother learn to read?) but it was not through networking itself that I learned to read. Reading is a skill and develops over time. The school system – teachers in particular – continued to develop my reading skills. Networking probably helped but it was not the only way I developed such skills. A theory of learning that fails to encompass these other approaches to learning is a weak if not useless theory.

Connectivist pedagogy

the connectivist principle of pedagogy would read: “to teach is to model and demonstrate; to learn is to practice and reflect”….

in connectivism, knowledge is not understood as the content that is transferred from person to person, but rather, knowledge is the network that is grown and developed from interactions with other entities in the network and in the world generally. Hence the objective of teaching is to stimulate such interactions, which is achieved by modeling and demonstrating the relevant sort of activity.

This is, to say the least, somewhat imprecise. Model and demonstrate what? What you have learned? What ‘networks’ have learned? Are all networks equal?

There is no recognition in the theory of connectivism of the priorities of what is to be learned, or in what order, no recognition of the utility of learning (making relationships, being a citizen, knowing how to do things that are important/valuable not only to the individual but also to society).

I do agree with Downes that humans are ‘programmed’ to learn – they will learn on their own. Again though this is not new. This was noted 300 years ago by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. But education is concerned with helping learners (from the Latin ducare, to lead) to learn, not only about what it is important to learn but also the most effective ways to do it.

Downes’ position is consistent with his distrust of educational systems. His view is that learning best occurs through informal networking and connections, and knowledge is created through the networks that learners belong to. Thus there is no need for formal education systems other than to support such networking.

[Please note correction to an earlier version where I said that Stephen was an auto-didact. This is incorrect – he was not home tutored, but went through the regular education systems in Ontario and Alberta.]

We still need a 21st century theory of learning

It took me so long to write this piece because I do believe Stephen Downes is right in saying that we need a theory of learning that reflects the massive changes that have occurred over the last 30 years, and I feel very uncomfortable in criticising his theory. The Internet and social media have clearly disrupted the way people learn. What constitutes knowledge has been profoundly challenged as a result. Stephen Downes has made a brave attempt to address this issue.

However, it is not a question of ripping up everything from the past and trying to construct something completely new. Stephen is wrong to say that psychologists have not contributed to our understanding of teaching and learning (even if their wisdom is infrequently applied). We have to build on what we have learned about learning and teaching in the past, and to adapt or amend this to take account of more recent developments.

Above all, Stephen chooses to ignore the social and economic factors that influence teaching, learning and the construction and use of knowledge. Learning does not take place in a (networked) vacuum. Connectivism for me is too far removed from the reality of learning as it actually occurs; above all it lacks empirical validation and an accommodation of previous work in this area. So, yes, we do need a new theory of learning for the 21st century, but I’m afraid that the theory of connectivism is not it.

You can see Stephen’s repudiation of my critique here: https://halfanhour.blogspot.com/2022/02/the-cognitive-level.html.Basically his response is deny cognitivism as having any value in our understanding of learning. Here we must agree to disagree.

References

Bates, T. (1986) Computer‑assisted learning or communications: which way for information technology in distance education? Journal of Distance Education Vol. 1, No. 1

Harasim, L. (2017) Learning Theory and Online Technologies New York/London: Routledge

Hiltz, R. and Turoff, M. (1978) The Network Nation: Human Communication via Computer Reading MA: Addison-Wesley

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.