OECD (2021) The state of school education: one year into the Covid pandemic Paris, France: OECD, pp. 50

The [Covid-19] crisis has revealed the enormous potential for innovation that is dormant in many education systems, which often remain dominated by hierarchical structures geared towards rewarding compliance. Governments can help strengthen professional autonomy and a collaborative culture where great ideas are refined. Investing in capacity development and change-management skills will be critical; and it is vital that teachers become active agents for change, not just in implementing technological and social innovations, but in designing them too.

Andreas Schleicher, Director for the OECD Directorate of Education and Skills

What is the report about?

The OECD collected comparative education statistics to track developments throughout the pandemic, looking at aspects that range from:

- lost learning opportunities and strategies to compensate;

- the organisation of learning and the working conditions of teachers;

- issues around governance and finance.

The focus is on school (k-12) systems.

Methodology

This survey, which reflects the situation as of 1 February 2021, was a collaborative effort between the OECD, UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank, which jointly designed the survey which was then administered by the OECD for its members and partners and by UNESCO for other countries. The data were provided by government authorities.

Note: as in other OECD reports on education, Canada is often missing in the results, partly because education is a provincial, not a national, policy and so national statistics are often lacking.

Main results

As always, this is my personal selection from a long list of results, and misses some of the nuances and qualifications available in the actual report. My focus is on results that are relevant to online and digital learning.

I am quoting mainly from Andreas Schleicher’s editorial, which in my view often goes beyond what the data actually says.

Please read the full report for a more comprehensive account of the main results.

- [In 2020] 1.5 billion students in 188 countries were locked out of their schools

- The crisis has exposed the many inadequacies and inequities in our school systems – from the broadband and computers needed for online education, through the supportive environments needed to focus on learning, up to the failure to enable local initiative and align resources with needs.

- Some countries were able to keep schools open and safe even in difficult pandemic situations. Social distancing and hygiene practices proved to be the most widely used measures to prevent the spread of the Coronavirus, but they imposed significant capacity constraints on schools and required education systems to make difficult choices when it came to the allocation of educational opportunity.

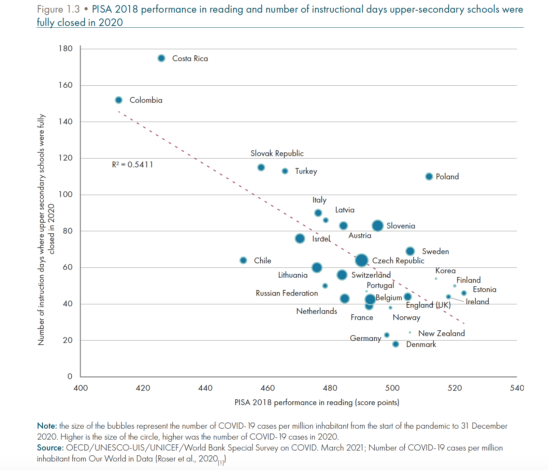

- Infection rates in the population appear unrelated to the number of days in which schools were closed. In other words, countries with similar infection rates made different policy choices when it came to school closures

- The countries with the lowest educational performance tended to fully close their schools for longer periods in 2020; the crisis did not just amplify educational inequalities within countries, but it is likely to also amplify the performance gap among countries

- Where school capacity was limited because of social distancing, most countries prioritised young children and students from disadvantaged backgrounds for learning in presence, reflecting that the social context of learning is most important for these groups, while digital alternatives are least effective for them

- Countries also relied on a range of approaches to ensure inclusiveness in distance education. This included flexible and self-paced digital platforms as well as agreements with mobile communications operators and internet firms to enhance access, particularly at the primary level of education.

- Local capacity was key for a safe opening of schools. Success often depended on combining transparent and well-communicated criteria for service operability, with flexibility to implement them at the frontline. The latter often included local decisions as to when to implement measures of social distancing, health, quarantine or the closures of classes or schools.

- During school closures, digital resources became the lifeline for education and the pandemic pushed teachers and students to quickly adapt to teach and learn online. Virtually all countries have rapidly enhanced digital learning opportunities for both students and teachers and encouraged new forms of teacher collaboration. The responses from the Special Survey show consistent patterns across countries: Online platforms were extensively used at all levels of education, but particularly so at the secondary level. Mobile phones were more common at the secondary level and radio at the upper-secondary level. Takehome packages, television and other distance-learning solutions were more common at the primary level.

- Digital learning systems not only just teach students, but simultaneously can observe how students study, the kind of tasks and thinking that interest them, and the kind of problems they find boring or difficult. These systems can then adapt learning to suit personal learning styles with far greater granularity and precision than any traditional classroom setting possibly can

- The crisis caught many education systems cold: the Special Survey documented major limitations in access, quality, equity and use of digital resources for learning and teaching.

- Moving beyond the pandemic, it will be important to continue monitoring how distance learning solutions are addressing the needs of different students and expand their opportunities for quality learning.

- Effective learning out of school during the pandemic placed much greater demands on autonomy, capacity for independent learning, executive functioning and self-monitoring. The plans to return to school need to focus on more intentional efforts to cultivate those essential skills among all students.

- Countries that could draw on multiple modes of assessment in pre-pandemic times found it easier to substitute examinations with other ways to recognise student learning.

- The transition to online or hybrid teacher professional learning has been an additional challenge for many teachers who were not familiar with online learning formats. The Special Survey shows how most countries made major efforts to support teachers’ learning online during the pandemic.

- Governments cannot innovate in the classroom; but they can help by opening up systems so that there is an evidence-based innovation-friendly climate where transformative ideas can bloom.

My comments

This is a useful record of how school systems in many countries responded to the Covid-19 crisis, at least at a policy level. It does not though attempt to measure the impact on learning, other than note the number of days lost to teaching through school closures. This assessment of the lasting impact of school closures will need to come later, when school re-openings are completed, and education returns to something like normal.

What does come through from this report for me is the importance of local autonomy on the one hand, necessary for responding appropriately to local conditions, which in a pandemic can vary widely, while at the same time having some national co-ordination and policies in place that support local decision making (funding flexibility being the most obvious).

I do have to say though that the report in places is clearly written by economists and policy wonks. While reflecting what governments did or did not do, the report fails to reflect many of the main educational challenges that teachers, students and parents faced as a result of the move to remote learning. For instance, what are the implications of greater use of digital learning for the initial training and in-service development of teachers post-pandemic? What role should parents play when students are increasingly expected to study digitally at home? What are the implications for the design of curricula for different age-ranges in a hybrid or blended learning world? These are all questions that remain to be addressed, more likely by school authorities and teachers within individual countries, than by the OECD. Nevertheless, historians may well find this report a useful snapshot of the impact of Covid-19 on school systems.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.