Transitioning from panic to control

Planning is a bit of a luxury in a crisis. You do triage until you can get back to normal. Also, no-one at the moment really knows when ‘normal’ will start again. What we can be sure about ‘normal’ after Covid-19 though is that it won’t be the same as normal before it, at least with respect to online learning.

Many instructors will have found that their courses in the end worked out perfectly well remotely and some will even prefer to teach them fully or partly online in the future; others will have found it a disaster. Probably most though will have found some things worked well, while other things didn’t, but those other things could in the main be fixed for the future.

Even though many instructors are still desperately getting their courses somehow delivered so that the spring semester can be saved, and emergency measures will probably have to continue into the fall semester, institutions need to start thinking NOW about what happens once life starts returning to normal, because time is needed to prepare properly to ensure good quality online courses and programs. It would also be wise to collect data and evidence about what worked and what didn’t, so that in another crisis everyone will be better prepared.

So here is a short list of what I think institutions should be doing now.

1. Develop or update your digital learning strategy

Everybody needs a best friend, and the best friend for a university or college administrator or senior manager at this time is an agreed strategy or plan for digital learning. I prefer the term strategy, because you need something that can constantly evolve and develop, while a plan sounds somewhat static to me. (In theory, a plan will consist of a number of ‘action’ strategies, as well as a number of other components – see (2) below). Without an agreed strategy or plan, though, you will have no direction or priorities, so will be subject to the whims of every faculty member or administrator in panic mode. (‘Buy Zoom!’ – ‘No – it’s not safe; we could be Zoombombed!’).

Because we are in a fast-developing technology era, terminology is also developing. Online learning is often associated with distance education, but more and more it is being ‘blended’ with campus-based teaching. E-learning is a term often used to encompass both blended and online learning. Other technology developments such as serious games or virtual reality may not be online but are certainly digital, so I prefer ‘digital learning’ as a term that encompasses all these developments, although you may need a sub-set of strategies for each type of digital learning.

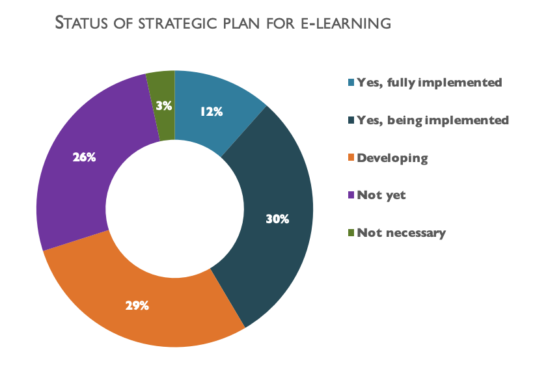

The CDLRA in its national survey of online learning in Canadian post-secondary institutions (Donovan et al., 2019) found that in 2018, 42% had an e-learning plan/strategy or were implementing one, 29% were developing one, and only 3% did not think an e-learning plan was necessary.

However my guess is that many of these plans were very conservative and may need to be updated or revised significantly as a result of the experience of remote learning resulting from the Covid-19 crisis. In any case more than half of Canadian post-secondary institutions do not currently have a fully developed plan or strategy for e-learning/digital learning.

Also, as everyone knows, getting a plan agreed is one thing; implementing it is quite another, so probably it will be necessary to revisit the implementation part of many existing plans or strategies. What might have been left to departments to implement gradually may need to be implemented much more quickly across the institution.

So, start NOW on ensuring you have an up-to-date, viable digital learning strategy or plan that is in place in time for the fall semester (even if – or especially if – the return to campus-based teaching is delayed then).

2 .What should be in a digital learning strategy or plan?

This can vary from institution to institution, but I would expect to see the following in most plans:

- The rationale for change

- The outcomes desired as a result of the change (e.g. more access; better skills, preferably well defined)

- Actions needed to support the changes (e.g. new course designs/teaching methods; use of OER/open textbooks; more faculty development; strengthen the Centre for Teaching & Learning; upgrades or changes in IT infrastructure and support; a communications strategy, etc.), with a timeline and budget for each

- Responsibilities at different levels (senior administration, department heads/Deans, individual faculty, students, IT, student services, Library, etc.) throughout institution for the implementation of the plan

- Possibly targets and timelines (e.g. 50% blended learning by 2025; 70% of faculty with a certificate in digital learning by 2030; all first and second year courses with open textbooks, etc. by 2022)

- A financial strategy and identified resources to enable implementation

- A strategy for evaluating implementation and outcomes

- A strategy for amending and up-dating the plan on a continuing basis

In particular, the financial strategy is essential. Too often plans fail to get implemented because inadequate resources are identified and allocated. This will cost money. There will not be a better time time to nail this down. Institutions may need specific government funding for this, or the use of capital reserves or endowment funds if necessary. It is a wise investment to make institutions crisis-resilient while at the same time improving the quality of teaching. This is not a hard case to make to government or the board of governors.

There should be a carefully crafted process, probably relying on a small task force, to reach consensus on the strategy, involving consultation with senior administrators, faculty and students, but on a tight timeline. Institutions starting from scratch may well have to delay acceptance of such a plan until later in the year than the fall semester. In large institutions, it will probably be necessary for each faculty or department to have its own sub-set of strategies for implementation.

However, I cannot overstress the urgency of getting a workable strategy in place by September, even if full implementation may take longer. The strategy will be a valuable guide to short-term decisions that may need to be made if the return of students to campus is delayed in the fall.

3. Collect and track data

Ideally, the plan would be based on data such as online enrolments, results of emergency action this semester, etc., but these will likely come too late for a plan or strategy to be in place by September, although such data and experience will be valuable for amending or tweaking strategy later.

What institutions should be doing now though is the following:

3.a. Establishing clear definitions of modes of teaching

Digital learning is fast evolving, and any definitions are likely to be obsolete within a short period. However, we do need some agreement on what we are doing and talking about. We can change definitions when the situation changes but at any point in time we need to be sure we are talking about the same thing. Without clear definitions, we cannot accurately track developments.

Fortunately, some basic groundwork has already been done. In 2019, the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association surveyed all universities and colleges in Canada, and found (Donovan et al., 2019) a good deal of agreement on the definitions of:

- distance education

- online courses

- blended/hybrid courses.

In addition, the CDLRA is making a distinction between ’emergency remote learning’ and ‘online learning’ as follows:

- Emergency Remote Teaching: “is a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances. It involves the use of fully remote teaching solutions for instruction or education that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face or as blended or hybrid courses and that will return to that format once the crisis or emergency has abated.” (direct quote from Erasmus paper: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning)

- Online Learning: A form of distance education in which a course or program is intentionally designed in advance to be delivered fully online. Faculty use pedagogical strategies for instruction, student engagement, and assessment that are specific to learning in a virtual environment.

3.b. Collect accurate enrolment data and completion rates by type of digital and remote learning

These definitions give us a base for tracking how different institutions responded to the Covid-19 crisis. However it is important that institutions flag correctly the courses under each definition, so that enrolments and outcomes can be tracked. This will enable institutions to compare the outcomes of different approaches to the Covid-19 crisis. For instance what is the difference in completion rates for previously designed and developed online courses compared to emergency remote learning courses that used other methods?

CDLRA already has extensive data on online enrolments from each institution for the years 2017 to 2019, so will also be able to report on how online enrolments will have changed in 2021, by province, type of institution and size of institution, for example.

More importantly, having good, well-defined internal data will enable institutions to track more accurately the outcomes of their digital learning strategies, and amend accordingly.

4. Hire the right staff now

Whatever your institutional strategy or plan for digital learning, you probably do not have enough support staff for digital learning, in particular, instructional designers, app software developers, web designers, and media producers. Digital learning is not going away after Covid-19 but will increase and grow.

Institutions will find themselves in the same position as state or provincial governments with N-95 surgical masks. There aren’t enough to go round, and everyone is competing with each other for scarce resources. So if there is any financial slack at all in your institution, start advertising for these people now as it will take three months to find, select and hire them.

It would be good if the numbers are already identified in an existing plan, perhaps a gradual growth over three to five years, but you are going to need them in September for sure now (see (5) below).

This also probably means ramping up or starting new programs to train professionals in the design and implementation of digital learning, such as UBC’s MET program or the MALAT program at Royal Roads University. However more programs are needed particularly from institutions in the rest of Canada.

5. Start developing an institution-wide faculty development program for digital learning

The biggest challenge with digital learning is that for it to be effective you need to move away from the lecture delivery model to other ways of teaching (see Teaching in a Digital Age). This is going to affect every instructor, so how are they going to be re-trained? This is a huge issue and I was interested to see today that the government of Québec has set aside $20 million for companies to pay for retraining their employees, including in remote working. We need a similar effort to re-train instructors in teaching for digital learning.

One part of such a program that should be put in place immediately is a 20 hour online course about teaching online and digitally for existing faculty and instructors that could be shared across institutions in the same province (or even better as an open educational resource). This could be developed and ready for September if started now – indeed there are already such open access courses for instructors already out there (see for instance Athabasca University’s MOOCs or Lethbridge College’s Facilitation Online Learning Open Course. No need to build these from scratch; there’s possibly one near you.

Conclusion

There are probably lots of other things that need to be done between now and September, but preparing for a big change in teaching methods from September onwards must surely be the most important, and we need to think about what needs to be done from now on to prepare for that. We owe it to our students that we are better able to support them when they do return.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Tony,

AU has a blended learning course for educators. http://cde.athabascau.ca/courses/mooc.php

Dr. Marti Cleveland-Innes is teaching/developing this and other MOOC/courses and has the resources at hand for creating additional faculty training.

Many thanks, Barb: duly noted

Thanks for showcasing your points on this in current situation