Happy anniversary, ETUG!

Last week I spent two days at the British Columbia Educational Technology Users’ Group conference at Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops. ETUG was celebrating 25 years of existence, since it was established in 1994 through the merging of several smaller groups. The conference theme was ‘Back to the Future.’

ETUG’s parent was the BC Standing Committee of Educational Technology, which was set up in 1990. I was one of the original committee members, representing the Open Learning Agency. Other founding members were Jim Bizzocchi (from SFU), Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa from what was then Malaspina Community College and, Randy Bruce, who I think was representing BCIT. I’d welcome any other names of that original committee, and my apologies for my poor memory.

A little history

It’s worth looking at what technologies were around (or rather, not around) at that time. Here are some of the technologies that were not publicly available in 1990:

- World Wide Web (publicly released, 1991)

- Web browsers: Netscape (actually registered as a company in 1994), Internet Explorer (1995), Google (1998)

- Learning management systems (the first, WebCT, was not developed until 1995 – at UBC)

- Laptops (the Mac Powerbook was launched in 1991)

- digital, cellular mobile phones (2G – 1991)

- Wi-fi (publicly released 1997)

- pdfs (1993)

The main technologies used in education in 1990 were the following:

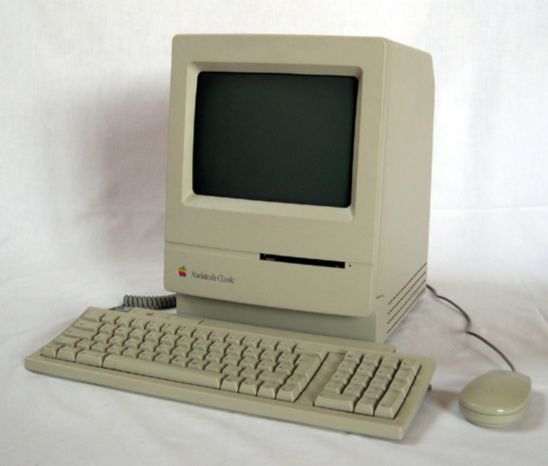

- computer hardware: desktop computers running MS-DOs with 40 MB hard drive at around US$3,000 each; Macintosh Classic, with 4 MB memory and a floppy disc hard drive, at around US$1,000. The low cost and ease of use of the Macintosh Classic, introduced in 1990, led to its widespread use in education. (Incidentally I have never used a non-Apple PC as my desktop in my whole career – I have always stuck with Apple)

- computer software: Microsoft Office (including Word, Excel and Powerpoint – however, digital output of Powerpoint from computers to an electronic overhead projector did not come until 1992)

- desktop publishing was the primary method for producing distance education materials, which were then mailed to students

- overhead projectors and plastic transparencies, on which one could write using a non-permanent, washable color marking pen: this was the main method used for classroom lectures although you could also use properly printed transparencies if you had the time and know-how

- 35 mm slide projectors (using a carousel and projector)

- email (BITNET, 1981; MCI Mail, 1983; Lotus Notes, 1989)

- television: however, production and transmission was in analog form (NTSC in North America, PAL in Europe) and very expensive to produce, requiring a large studio. There were though active educational television networks operating in 1990, including Knowledge Network in British Columbia and TV Ontario. Both still exist today.

- video-cassettes and audio cassettes (DVDs did not appear until 1993)

- audio-conferencing was used extensively in distance education in 1990 (video-conferencing was too expensive for teaching)

- books (high school kids and college students were getting back problems from carrying so many books from class to class in the 1990s)

As a result, educational technologists as such were split across various disciplines: instructional designers, print editors, video and audio producers, IT programmers and network operators, and were often in separate professional groups. ETUG in 1994 enabled these groups to come together.

It can also be seen in retrospect that the early 1990s was one of the most prolific times for the development of what are now commonly used technologies in education. Thus the importance of developing a community to explore and share knowledge about the benefits and limitations of these emerging technologies is now obvious, so congratulations to those with the foresight to establish ETUG in 1994.

Lastly, it’s worth asking how much has changed in teaching and learning since 1990, despite this amazing technology development. This was a theme that ran through the 2019 conference presentations and I will discuss this below.

The 2019 conference

As always, these are very personal comments, reflecting on what I saw/attended and what I am interested in.

Defining and applying open pedagogy

Is open pedagogy the innovation that will really radically change education? I went to several sessions where presenters (and participants) were struggling with the definition and application of open pedagogy.

Textbook-free courses

The team from Royal Roads University’s Masters of Arts in Learning and Technology (MALAT) discussed how they were attempting to foster a culture of openness in the program. This program is the first master of arts degree in Canada to go textbook-free. Students can access all of the course materials through open educational resources, e-books, journal articles and other free digital resources. These types of courses, dubbed “Zed Creds” or “Z-degrees”, aim to improve access to education and enhance student outcomes. As with several other presentations, this was as much about audience participation in helping with the practicalities of such an approach as about lessons learned to date about what works and what doesn’t in instilling a culture of openness in a program. For more information about this initiative, contact Elizabeth Childs [Elizabeth.Childs@RoyalRoads.ca]

Open pedagogy infrastructure

On the infrastructure side, there was a report on the work of the OpenETC movement, ‘a community of educators, technologists, and designers sharing their expertise to foster and support open infrastructure for the BC post-secondary sector.’ The aim is to expand as far as possible the use of open source materials across the BC post-secondary education sector. Their web site brings together not only over 70 existing open source tools that can be used in education, but also a community of developers of new open source tools for education. The main players: Brian Lamb (TRU); Clint Lalonde (BCcampus); Grant Potter (UVic); Tannis Morgan (JIBC/BCcampus).

Open pedagogy publishing

At another session, ‘Rethinking learning design’, another group (membership of these three groups overlaps a good deal, of course) is working on designing an open access approach to a textbook (or course) on instructional design/learning design that adheres to all the principles of open pedagogy. Again, this was a brainstorming session with participants about opportunities and barriers to such an approach. The main players: Irwin de Vries (TRU); Michelle Harrison (TRU); Tannis Morgan (JIBC/BCcampus); Michael Paskevicius (UVic).

I was particularly interested in this session, as I myself am in the process of revising my own open textbook, ‘Teaching in a Digital Age.’ I have run into several problems in making the book adhere to open pedagogy principles, mainly to do with Pressbooks, the software used to create the book. Pressbooks, based on WordPress, has been superb for:

- being able to start writing the book almost immediately, with almost no prerequisite training (18 months from inception to publication)

- making the book easily accessible in many different formats (nearly half a million downloads so far)

- for enabling translation into other languages (10 so far)

- for enabling others to re-use, and redesign, the book for their own purposes, through cloning and open access for editing/rewriting. (It’s been adopted on over 60 courses, to my knowledge).

However, Pressbooks is not only structured like a traditional book, with chapters and sections in sequence, it also lacks some of the essentials for student interaction and activities. In particular, an open textbook based on open pedagogy principles should be able to provide:

- an open area for comments on each section, that can go back to the author as well as or instead of an instructor using the textbook in a course

- software to enable interaction between readers/students/instructors/the author, i.e. a built-in open but secure forum

- a text box for advance organisers, such as desired learning outcomes, and the connection with previous and subsequent sections

- a text box or function for open-ended follow-up activities by the reader (I provide general feedback via a short podcast)

- multiple versions so that instructors and students can offer and add their own version of the book, while retaining the integrity of the original version.

I have tried incorporating H5P, but this takes a very behaviourist approach to student interaction, depending heavily on pre-set answers. This is great for many subject areas or topics, but not for my book. In my book, I want to offer open-ended activities and opportunities for reflection which require a built-in activity box (BCcampus provided this as an add-on to its original theme for Pressbooks, but has now reverted to the more publicly available themes such as McLuhan, which do not have these pedagogical features.)

These are all solvable technical problems, but need new programming and/or additions to the current Pressbook themes. I therefore welcome the efforts of the ‘Rethinking Learning Design’ group to break out of the technology barriers to open pedagogy, but I do wonder if they realise the size of the problem they are facing. It may be better to use a combination of existing open publishing tools such as Pressbooks with other loosely attached resources such as a discussion forum, and more open activity functions that can be linked or bolted on to the main publishing tool. Not perfect but more pragmatic.

Making open pedagogy more concrete

I am proud that here in British Columbia we have a significant number of people pushing the boundaries of open pedagogy in a variety of ways. This research and exploration of open pedagogy is much to be admired.

However, sooner or later I would like to see a development beyond theory and ideas and experimentation into more concrete guidelines for instructors on how best to teach using an open pedagogical approach. Much of this is now ‘out there’ but it needs to be better organised and structured and more evidence-based if open pedagogy is to spread more widely and become more firmly established in education. Time for an open textbook on open pedagogy? Or is that an oxymoron?

Other conference highlights

Very briefly (this post is already too long):

- Dr. Maren Deepwell of ALT, UK described an interesting initiative in the UK to provide professional accreditation of learning technologists, operating at three levels (novice, career, advanced) through certified membership of ALT (Association of Learning Technologists). It uses a combination of personal portfolios of work and peer assessment. This would be valuable in Canada, either for those who do not have the time or resources to take a full professional masters, such as UBC’s MET or RRU’s MALAT, or as continuing professional education after their masters.

- I presented specifically on the results for British Columbia institutions of the 2018 national survey of online learning, and had a very good discussion session about the implications of the results for teaching and learning in BC post-secondary education. The presentation slides are available from here: [Scroll down the schedule then click on the national survey presentation then click on the pptx icon below the speaker details.]

- I attended an excellent session by Junsong Zhang of Kwantlen Polytechnic University on the educational factors that need to be considered when designing VR for educational purposes

- there was an excellent rock band made up of boomer TRU staff following the conference dinner; John Churchley of Thompson Rivers University sang a plaintive song of educational development (‘I aint got my Moodle no more’) in which he managed to insert the names of dozens of educational technologies, and Ian Linkletter of UBC gave a devastating account of what happens when you dare to criticise publicly an Internet tech giant.

Final reflections on the future of ed tech in BC

I sincerely believe that open pedagogy has the potential to revolutionise the way we teach in a way much more relevant to the needs of students and learners in a digital age than current approaches. However, it is not the only issue facing educators and institutions in British Columbia’s post-secondary education system and I believe the BC government, BCcampus and ETUG need to give as much importance to these other developments as to open pedagogy:

1. Blended and hybrid learning

This is an issue that every institution is increasingly facing. In particular how do we ensure quality teaching in blended learning environments? We need to find ways to scale up support for all faculty and instructors as they move into this area. However, we don’t have established best practices in this field and we don’t therefore have convincingly good guidelines to give instructors. This means tracking how instructors are designing their blended learning and evaluating what works and what doesn’t, but also using what we do know about good learning design in general and applying that to blended and hybrid learning.

2. Faculty development

Secondly faculty development and training in the use of learning technologies remains the number one barrier to successful digital learning, and not just in British Columbia. We need to test and implement models that enable instructors to get the support they need on a just-in-time, on-demand manner. The issue is not just about open pedagogy, although it is one possible part of the solution. However, such development and training needs to include methods for the appropriate selection and use of technology and media, and we also need some professional development programs for senior management on planning and strategies for digital learning.

3. Curriculum reform

Thirdly we need curriculum reform – new learning outcomes and methods of teaching that will enable such outcomes – if we are to develop students with the knowledge and skills they need in a digital age.

4. New technology

Lastly technology continues to change and develop. In particular, virtual and augmented reality, simulations and games, learning analytics and the potential and consequences of AI on teaching and learning are all burning issues that need the consideration and input of educational technologists.

Thus there is a lot of work that needs to be done beyond the promotion of open pedagogy. The ETUG conference was very useful in enabling me to clarify some of these issues in my own mind – learning from the past in order to prepare better for the future. Thank you, ETUG!

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

I was reading Noddings and Enright’s 1983 article “The Promise of Open Education” (https://www.jstor.org/stable/1476891) yesterday and thinking about how it might apply today to open pedagogy. They talk of open education as a movement that failed and a model that lives on, and also a model that has been around for a long time. Open education suffered from the lack of a clear definition which made it difficult to discuss and difficult to defend. The very language patterns of education worked against the acceptance of open education. They saw open education as characterized by a set of beliefs that open educators held and which informed their practices, rather than open education as a set of rules and practices unto itself. Is open pedagogy in a similar situation? Is it a new manifestation of an old idea? Will it be self-defeating to promote open pedagogy to people who do not share the philosophical heritage?

Excellent point, Paul.

I agree that open education is more a movement, a philosophy, but it also has powerful practical manifestations, such as open universities, open textbooks, open resources, and open source software. If open pedagogy is to succeed it must also find similar relevant manifestations, in terms of teaching methods or ways of learning. Perhaps advocates of open pedagogy would like to provide some examples.