The story so far

Chapter 5 of my open textbook, ‘Teaching in a Digital Age’ is about the design of teaching and learning, which I am currently writing and publishing as I go.

I started Chapter 5 by suggesting that instructors should think about design through the lens of constructing a comprehensive learning environment in which teaching and learning will take place. I have started to work through the various components of a learning environment, focusing particularly on how the digital age affects the way we need to look at some of these components.

I started by looking at how the characteristics of our learners are changing, and followed that by examining how our perspectives on content are being influenced by the digital age. In this post, I look at how both intellectual and practical skills can be developed to meet the needs of a digital age. The following posts will do the same for learner support, resources and assessment respectively.

This will then lead to a discussion of different models for designing teaching and learning. These models aim to provide a structure for and integration of these various components of a learning environment.

Scenario: Developing historical thinking

Ralph Goodyear is a professor of history in a public Tier 1 research university in the central United States. He has a class of 120 undergraduate students taking HIST 305, ‘Historiography’.

For the first three weeks of the course, Goodyear had recorded a series of short 15 minute video lectures that covered the following topics/content:

- the various sources used by historians (e.g. earlier writings, empirical records including registries of birth, marriage and death, eye witness accounts, artifacts such as paintings, photographs, and physical evidence such as ruins.)

- the themes around which historical analysis tend to be written,

- some of the techniques used by historians, such as narrative, analysis and interpretation

- three different positions or theories about history (objectivist, marxist, post modernist).

Students downloaded the videos according to a schedule suggested by Goodyear. Students attended two one hour classes a week, where specific topics covered in the videos were discussed. Students also had an online discussion forum in the course space on the university’s learning management system, where Goodyear had posted similar topics for discussion. Students were expected to make at least one substantive contribution to each online topic for which they received a grade that went towards their final grade.

Students also had to read a major textbook on historiography over this three week period.

In the fourth week, he divided the class into twelve groups of six, and asked each group to research the history of any city outside the United States over the last 50 years or so. They could use whatever sources they could find, including online sources such as newspaper reports, images, research publications, and so on, as well as the university’s own library collection. In writing their report, they had to do the following:

- pick a particular theme that covered the 50 years and write a narrative based around the theme

- identify the sources they finally used in their report, and discuss why they selected some sources and dismissed others

- compare their approach to the three positions covered in the lectures

- post their report in the form of an online e-portfolio in the course space on the university’s learning management system

They had five weeks to do this.

The last three weeks of the course were devoted to presentations by each of the groups, with comments, discussion and questions, both in class and online (the in class presentations were recorded and made available online). At the end of the course, students assigned grades to each of the other groups’ work. Goodyear took these student gradings into consideration, but reserved the right to adjust the grades, with an explanation of why he did the adjustment. Goodyear also gave each student an individual grade, based on both their group’s grade, and their personal contribution to the online and class discussions.

Goodyear commented that he was surprised and delighted at the quality of the students’ work. He said: ‘What I liked was that the students weren’t learning about history; they were doing it.’

Based on an actual case, but with some embellishments.

Skills in a digital age

In Chapter 1, Section 1.4, I listed some of the skills that graduates need in a digital age, and argued that this requires a greater focus on developing such skills, at all levels of education, but particularly at a post-secondary level, where the focus is often on specialised content. Although skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and creative thinking have always been valued in higher education, the identification and development of such skills is often implicit and almost accidental, as if students will somehow pick up these skills from observing faculty themselves demonstrating such skills or through some form of osmosis resulting from the study of content. I also pointed out in the same section, though, that there is substantial research on skills development but the knowledge deriving from such research is at best applied haphazardly, if at all, to the development of intellectual skills.

Furthermore the skills required in a digital age are broader and more wide ranging than the abstract academic skills traditionally developed in higher education. For instance, they need to be grounded just as much in digital communications media as in traditional writing or lecturing, and include the development of digital competence and expertise within a subject domain, as well as skills such as independent learning and knowledge management. These are not so much new skills as a different emphasis, focus or direction.

It is somewhat artificial to separate content from skills, because content is the fuel that drives the development of intellectual skills. At the same time, in more traditionally vocational training, we see the reverse trend in a digital age, with much more focus on developing high level conceptual thinking as well as manual skills development. My aim here is not to downplay the importance of content, but to ensure that skills development receives as much focus and attention from instructors, and that we approach intellectual skills development in the same rigorous and explicit way as apprentices are trained in manual skills.

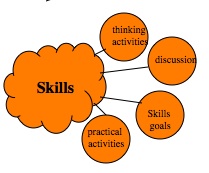

Setting goals for skills development

Thus a critical step is to be explicit about what skills a particular course or program is trying to develop, and to define these goals in such a way that they can be implemented and assessed. In other words it is not enough to say that a course aims to develop critical thinking, but to state clearly what this would look like in the context of the particular course or content area, in ways that are clear to students. In particular the ‘skills’ goals should be capable of assessment and students should be aware of the criteria or rubrics that will be used for assessment.

Thinking activities

A skill is not binary, in the sense that you either have it or you don’t. There is a tendency to talk about skills and competencies in terms of novice, intermediate, expert, and master, but in reality skills require constant practice and application and there is, at least with regard to intellectual skills, no final destination. So it is critically important when designing a course or program to design activities that require students to develop, practice and apply thinking skills on a continuous basis, preferably in a way that starts with small steps and leads eventually to larger ones. There are many ways in which this can be done, such as written assignments, project work, and focused discussion, but these thinking activities need to be thought about, planned and implemented on a consistent basis by the instructor.

Practical activities

It is a given in vocational programs that students need lots of practical activities to develop their manual skills. This though is equally true for intellectual skills. Students need to be able to demonstrate where they are along the road to mastery, get feedback on it, and retry as a result. This means doing work that enables them to practice specific skills.

In the scenario above, students had to cover and understand the essential content in the first three weeks, do research in a group, develop an agreed project report, in the form of an e-portfolio, share it with other students and the instructor for comments, feedback and assessment, and present their report orally and online. Ideally, they will have the opportunity to carry over many of these skills into other courses where the skills can be further refined and developed. Thus, with skills development, a longer term horizon than a single course will be necessary, so integrated program as well as course planning is important.

Discussion as a tool for developing intellectual skills

Discussion is a very important tool for developing thinking skills. However, not any kind of discussion. It was argued in Chapter 2 that academic knowledge requires a different kind of thinking to everyday thinking. It usually requires students to see the world differently, in terms of underlying principles, abstractions and ideas. Thus discussion needs to be carefully managed by the instructor, so that it focuses on the development of skills in thinking that are integral to the area of study. This requires the instructor to plan, structure and support discussion within the class, keeping the discussions in focus, and providing opportunities to demonstrate how experts in the field approach topics under discussion, and comparing students’ efforts.

In conclusion

There are many opportunities in even the most academic courses to develop intellectual and practical skills that will carry over into work and life activities in a digital age, without corrupting the values or standards of academia. Even in vocational courses, students need opportunities to practice intellectual or conceptual skills such as problem-solving, communication skills, and collaborative learning. However, this won’t happen merely through the delivery of content. Instructors need to:

- think carefully about exactly what skills their students need,

- how this fits with the nature of the subject matter,

- the kind of activities that will allow students to develop and improve their intellectual skills, and

- how to give feedback and to assess those skills, within the time and resources available.

This is a very brief discussion of how and why skills development should be an integral part of any learning environment. We will be discussing skills and skill development in more depth in later chapters.

Over to you

Your views, comments and criticisms are always welcome. In particular:

- how does the history scenario work for you? Does it demonstrate adequately the points I’m making about skills development?

- are the skills being developed by students in the history scenario relevant to a digital age?

- is this post likely to change the way you think about teaching your subject, or do you already cover skills development adequately? If you feel you do cover skills development well, does your approach differ from mine?

Love to hear from you.

Next up

Learner support in a digital age

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.