One term, many contexts

If I was uncomfortable writing my previous post, I am even more uncomfortable about writing this one. ‘Developing countries’ is not a term I like because there is a whole range of very different economic development covered by this term. Some countries for instance may be very powerful economically but may still have a very large proportion of the population who are still desperately poor. Some will have excellent internet connections in major cities and absolutely no connection in rural areas, and others everything in-between.

Secondly, it’s not for me to tell developing countries what they should do. My experience is that educators in ‘developing’ countries are far better than outside experts from ‘developed’ countries at finding solutions and approaches that work for them. For instance we can learn a lot in Canada about how to use mobile learning effectively from Africa, and Kenya in particular.

Nevertheless, I have heard almost cries of desperation from colleagues in developing countries about what their governments and institutions have or have not been doing regarding emergency online learning, so for those who are interested, let me share my thoughts on the topic of inequities and online learning as it affects ‘developing’ countries.

Should you even go online with your teaching?

The Internet (or wireless telephone) in many places is not just a question of off or on. Bandwidth can vary enormously. Even if students have Internet or wifi access, they need at least 10 Mbps for any form of video, but at 2 Mbps they can handle most text (without heavy graphics) and audio.

Ideally you should design your courses for the lowest bandwidth of Internet to which most students will have access. If most have 2Mbps or less, then forget Zoom, streamed video or the electronic distribution of graphic rich Powerpoint slides. However, if most are in the 2Mbps-10 Mbps range then you can use a learning management system for instance provided you stick to text, audio (e.g. podcasts) and simple graphics.

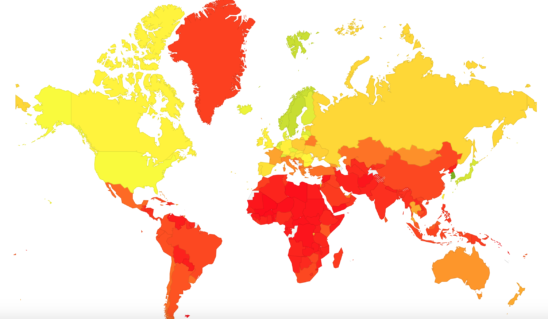

To find the average internet speed in your country as measured in 2017, go to: https://www.fastmetrics.com/internet-connection-speed-by-country.php You will see that one of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa with the highest average Internet speed is South Africa, at 4.7 Mbps. This – I’m guessing – means that in the larger cities, and for people who can afford high-speed access, coverage in South Africa’s cities is pretty good, but in smaller townships or rural areas, it is pretty poor or non-existent. (I’d really like to hear from South Africans on this – how wrong am I)?

So, in South Africa, if your students are at a university that attracts generally wealthy or middle class students, they can probably get 10 Mbps or better, so you may able to do limited streaming of lectures, but they still need to be short (no more than 20 minutes). Otherwise, you will need to stick to the LMS. If many of your students are in rural areas or are poor, online learning is not going to work even just using an LMS.

For most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, except perhaps for Ruanda and Kenya, online learning will be a non-starter for all but the wealthiest, urban students. I know many universities in sub-Saharan Africa have some online courses, but they are often targeted at a specific demographic, such as working, lifelong learners. It is quite another matter to move all your courses online for all students.

The other point to remember is the cost. Even though students may have coverage, online learning requires a lot of time spent online. There are several consequences:

- Watch the costs for students for being online: if it comes to a choice between studying and eating, you are not going to win

- Can you design activities that they can do offline? (e.g. reading textbooks)

- Can students download text – or can it be mailed – so they don’t have to access it ‘live’?

- If you are able to use video, keep it short (5-10 minutes maximum).

- Break the learning up into small chunks.

Moving all teaching online may make sense for a limited number institutions in developing countries, but for most it is not a realistic option.

Use the media that make most sense in your situation

Just because moving everything online makes sense in developed countries doesn’t mean that it is the best approach elsewhere. Although there are important differences between technologies, these differences are far less important than the methods of teaching we use. In other words, there are opportunities for substitution of one technology by another without much loss of learning effectiveness, provided that the replacement media is well designed and any loss of functionality is replaced in some other way.

Start by asking: who are your students and what access to technology do they already have? If more than say 30% of your students do not have adequate and regular access to that technology, either don’t use it or be prepared for a substantial amount of work finding alternative ways to deliver to that 30%.

What other media can be used?

It should be remembered that there were very successful distance education programs long before the Internet arrived. We can learn from this.

Radio

I once called radio the forgotten medium. Most students can access radio in one form or another. You can use it for lectures or for supporting other media such as text.

Many universities already have a student radio station. Or form a partnership with local radio stations to broadcast your courses – but make sure radio transmission can reach all your students.

Radio is a very cheap and easy medium once you have access to transmission. For instance you can record at home using your computer and an appropriate recording software, such as Garage Band (free with an Apple Mac).

Broadcast television

This is a more expensive option unless you already have a store of recorded programs or your own TV station. Nevertheless most students are likely to have access to television.

Again it may be possible to partner with a local television station – many TV stations want to be ‘good citizens’ and help with the Covid-19 crisis; morning or late night programs from the local university might be very welcome.

The problem is that you would need a huge amount of broadcast time to cover a whole university curriculum. Again, many short programs would be better than long one hour lectures.

Text (books, printed materials)

This is more difficult, because text needs preparation, printing and distribution, usually by mail. It is not therefore a ‘quick’ medium, unless, like UNISA, you already have a large print operation in existence.

However, faculty could prepare their own notes, and pdf copies could be printed and distributed. Again, avoid using Powerpoint slides, because they are not always self-explanatory and if in colour will be expensive to print.

If students already have computers, it would be more economical to collect the notes for a whole course on flash-drives and mail those to the students.

Social media/mobile learning

Students already have many apps on their mobile phones which can quite easily be used or adapted for teaching purposes. Also most learning management systems work well on mobile phones.

More importantly social media allow students and instructors to stay connected. Again, the usefulness of these will depend on how many of your students have mobile phones and the need to keep data/usage costs down for many students.

Design implications

Remember, it is better to reach 90% of students with a slightly less than perfect medium than to reach 50% with a more powerful medium. You are more likely to meet most students with a combination of media.

Also the more media the better: you can cover weaknesses in one medium (e.g. no visuals in radio) with strengths of other media (e.g. graphics in text). For instance research has shown that mathematics is taught more effectively combining audio with text than with either alone.

If you do start moving your courses to other media, you will probably need to re-think the overall design of your courses. (See https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/03/09/advice-to-those-about-to-teach-online-because-of-the-corona-virus/ for a quick introduction).

In any case, you need to talk to your educational technology experts, who should know what access you can get from internal facilities or other external media organisations such as broadcast companies.

Conclusions

There is probably not going to be one solution here for any single institution in a developing country. It may make sense to move some courses online, but use other media for the rest. In many cases, though, moving online will not be a good solution because of student access and cost.

On the other hand it may not be feasible to use other media, such as broadcasting or text. Again, some mix or combination of media may be necessary. For instance, to minimize the effect of the school closures on the education system, Iran’s Education Ministry introduced an online app, the Social Network of Students (Shad in Persian), and presents daily lessons for different grades on state TV. However, even in Tehran, not all children have smartphones. Some have to use their parents’ mobile devices to access course material, and not all parents have mobile phones.

In summary, the Covid-19 crisis will be an even bigger challenge for educational institutions in developing countries, because the alternatives and resources available are usually less than in developed countries. This is another example of the inequity caused by the coronavirus, rather than by online learning.

Over to you

I would love to hear from institutions in non-wealthy countries about how you are coping with the challenge of providing education during the Covid-19 crisis. Have your institutions just shut down? Are they moving online? What other strategies are being used?

References

Bizaer, M. (2020) Pandemic reveals Iran’s online-learning challenges Al-Monitor, April 17

FastMetrics (2020) Average Internet Speeds by Country Fastmetrics, accessed April 21

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.

Dr. Tony Bates is the author of eleven books in the field of online learning and distance education. He has provided consulting services specializing in training in the planning and management of online learning and distance education, working with over 40 organizations in 25 countries. Tony is a Research Associate with Contact North | Contact Nord, Ontario’s Distance Education & Training Network.